01/12/25

Dominion Cinema, Edinburgh

As if NT Live performances weren’t enough of a treat, we’ve recently ramped up the indulgence levels by choosing to watch them at Edinburgh’s most bougie cinema, the Dominion. At 3pm this afternoon, we zip up our raincoats and venture out into the December drizzle, ready for the half-hour walk that will take us to our huge, reclining seats.

The Fifth Step is a compact, one-act play by Jack Ireland, and its ninety-minute running time is perfectly judged. This is a tight and concentrated piece, where small impulses are magnified, vague doubts forensically explored. The in-the-round set, designed by Milla Clark, is almost brutalist, comprising a stark square with raised, cushioned sides, reminiscent of a boxing ring or a trampoline: a taut jump mat, ready to absorb the characters’ anger, or give them the push they need to set themselves free.

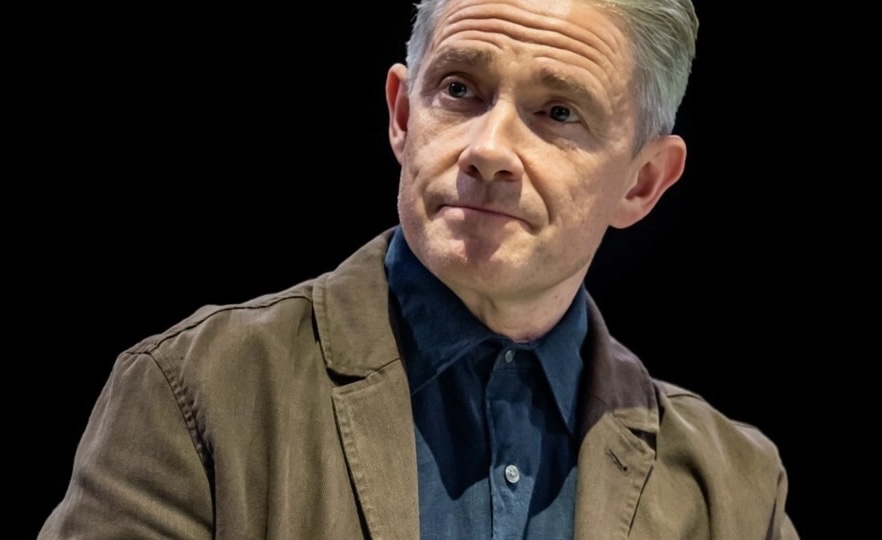

We’re in the world of AA, where acceptance meets strict protocols and kindness sometimes seems harsh. Jack Lowden plays Luka, a twenty-something alcoholic, scared that he’s turning into his dad, and desperate to avoid this destiny. Nervy and uncertain, he isn’t sure that he can do it, not when sobriety leaves a booze-shaped void he fills with loneliness and self-loathing. Hovering in the room after a meeting, he gets chatting to James (Martin Freeman), who has been on the wagon for more than twenty-five years. The older man knows exactly what Luka is going through, and offers to become his sponsor. From hereon in, we watch as their relationship develops – and as they both continue to battle against their respective addictions.

Ireland’s script is darkly funny, and director Finn Den Hertog maximises its comic potential, without ever belittling the men’s experiences. Not much happens, and yet all of human life is here: our frailty, our fabulousness; our bravado, our beauty; our destructiveness and our shared desperation. Luka begins by looking for easy answers: if he does whatever his sponsor says, then surely he’ll find happiness. But James has his own demons to grapple with and he knows that life is far more complex than that. You just have to keep on being honest, keep facing up to your own failings – and keep supporting one another along the way…

Unsurprisingly, Lowden and Freeman deliver faultless performances. They’re perfectly cast, Freeman’s wry stillness the ideal foil for Lowden’s twitchy, pent-up energy. A fascinating insight into not just addiction but also notions of authority and responsibility, this is definitely one to watch if it’s showing at a cinema near you.

4 stars

Susan Singfield