31/03/23

Cineworld, Edinburgh

Yann Martel’s novel, Life of Pi, was published in 2001 and won the Booker Prize the following year. In 2012, it was adapted into an impressive film, directed by Ang Lee. Of course, the inevitable next step was to adapt it for the stage, but that’s a very tall order. Would it be possible to convincingly present such a fantastical story in a theatre? Well, never underestimate what can be achieved with a suitable budget and state-of-the-art special effects. This version, beamed direct from London’s Wyndham Theatre as part of the NT Live season, is absolutely eye-popping.

The play opens in a hospital ward in Mexico, where our eponymous hero is being interviewed about his extraordinary survival in an open boat for 227 days, but his recollections are suddenly punctuated by a scene change so slick, I barely notice it happening, – until it has.

It’s the 1960s and Piscine Molitor Patel (Hiran Abeysekera) lives in Pondicherry, India. Named after a swimming pool in France, he prefers his adopted nickname ‘Pi.’ His parents run a small zoo and Pi and his sister spend much of their time looking after the animals – including the latest arrival, a fierce Siberian tiger called Richard Parker.

And now it’s 1976 and, due to violent political unrest, Pi’s parents have decided to relocate their animals to a zoo in Canada. Pi, his family and all the animals board the Japanese freighter Tsintsum, and set off on a sea voyage. What could possibly go wrong? Well, plenty, as it happens. Pi ends up stranded in a lifeboat with only a zebra, a hyena, an orangutan and er… Richard Parker for company.

Which is awkward, to say the very least.

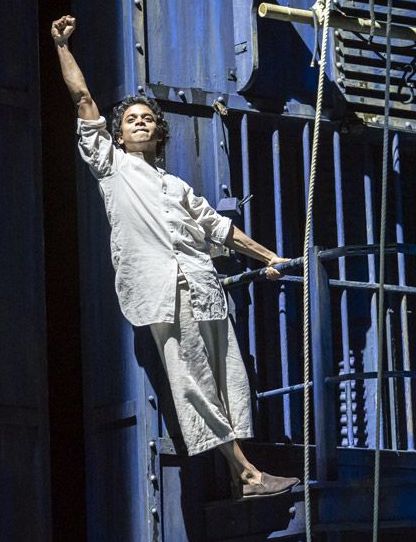

To give him his due, Abeysekara offers an extraordinary performance in the lead role but, as you might expect, his efforts and those of his fellow performers are somewhat dwarfed by the aforementioned puppetry and special effects, which are quite frankly, off the scale.

Let’s begin with Tim Hatley’s ingenious set designs, particularly those that deal with Pi’s adventures in the fateful lifeboat tossed upon stormy seas. Raging torrents of water appear to flood across the performance space, while shoals of fluorescent fish speed along just below the surface. I even gasp out loud at one point when Pi takes a nose dive onto an apparently solid stage… and disappears right through it, only to resurface in an entirely different spot a moment later. How have they done that? (With trapdoors, obviously, but it’s astonishing nevertheless.)

As are the animals – or, more accurately, the puppets, designed by Nick Barnes, which are so intricately made that I actually keep forgetting they’re mechanical, which is ridiculous because I can quite clearly see the people operating them… and yet… and yet, I still believe they’re real, which is some accomplishment. Richard Parker is, of course, la bête du jour, the very essence of feline power, even able to switch into a comedic role as a fan of haute cuisine and back to a snarling, powerful predator, but – to be fair – every creature I see, right down to the swarms of multi coloured butterflies, is an astonishing creations.

Adapted by Lolita Chakrabarti and directed by Max Webster, Life of Pi is like a magician’s box of tricks. There’s a small part of me that feels sorry for the cast of (mostly excellent) actors struggling to make themselves seen amidst all that sturm und drang, but I guess it’s just – ahem – the nature of the beast.

4.3 stars

Philip Caveney