11/10/24

Bedlam Theatre, Edinburgh

George Orwell’s dystopian masterpiece has loomed large over 2024 for us. In April, we listened to Audible’s star-studded ‘immersive’ audio adaptation, where Andrew Garfield, Cynthia Erivo, Tom Hardy and Andrew Scott brought Oceania memorably to life. Immediately afterwards, we both read Sandra Newman’s Julia, a reworking of the novel from the lead female’s point of view. And today we’re here at Bedlam Theatre, ready to see EUTC’s interpretation of the cautionary tale.

The use of screens projecting both pre-records (Lewis Eggeling) and live video (Tom Beazley) is inspired: there can’t be many stories more suited to a multi-media approach. The scene is set as soon as we enter the theatre: Big Brother (Thaddeus Buttrey) is watching us, a close-shot of his eyes filling the back drop. Instead of ushers, there are guards (Molly Gilbert, Rose Sarafilovic, Dylan Kaeuper and Fergus White), forbidding in their black uniforms, scarfs covering their lower faces. “All hand-held telescreens must be switched off,” one intones; “Silence!” bellows another. Predictably, we all comply.

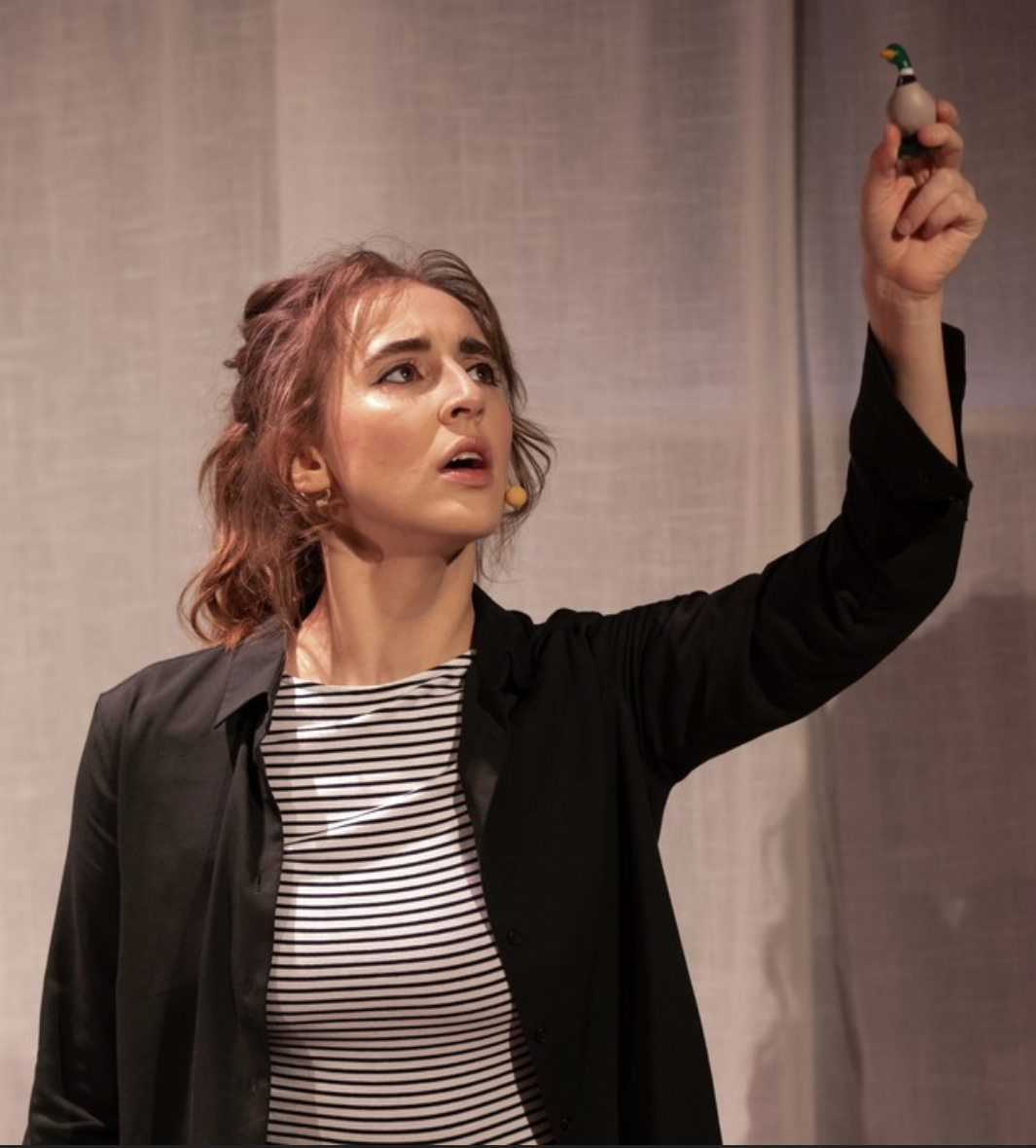

This adaptation (by Robert Owens, Wilton E Hall Jr, and William A Miles Jr) generally works well, plunging us immediately into the middle of the story. What used to be Britain is now part of Oceania, a sprawling dictatorship led by Big Brother, its impoverished citizens ruled with an iron rod by the unforgiving Party. By falling in love, Ministry of Truth workers Winston (Harry Foyle) and Julia (Francesca Carter) have broken the law and, having crossed that line, find themselves increasingly unable to swallow the propaganda they are fed. But what chance do they stand against the all-seeing apparatus of the State?

Director Hunter King does a great job of establishing a sense of threat, as well as highlighting the fragile humanity that endures, despite Big Brother’s best efforts to quash it. “They can make us say things,” as Julia acknowledges, “But they can’t make us think them.” As the central duo, Foyle and Carter both deliver flawless performances: Winston and Julia are convincingly reckless, persuading themselves that they are less vulnerable than they really are, caught up in the excitement of their affair. The story is so well known that there is a dramatic irony not present in the original plot, and King exploits this effectively, so that we find ourselves grieving for the couple even as their relationship blooms.

Robbie Morris is clearly having a whale of a time as smarmy backstabber, O’Brien, member of the Inner Party and chief snarer of the unwary. He plays the role as a kind of archetypal villain, complete with maniacal laugh, which makes for an interesting counterpoint, highlighting the freedom that comes with privilege: this is not a man who has ever felt the need to hide or even mute his feelings, unlike even the most loyal Party members. The only other character who seems uncowed is the landlady (Raphaella Hawkins), who owns the apartment Winston and Julia rent for their illicit lovemaking. As a Prole, she has a certain kind of liberty, born of being so poor and lowly that she’s considered unworthy of attention. It’s a dubious advantage.

As we’ve come to expect from Edinburgh University’s student shows, this is an impressive piece of theatre. I especially enjoy the fight sequences, directed by Rebecca Mahar, which are horribly credible and more brutal than I’m used to seeing on stage, ramping up the horror of this too-close-for-comfort imagined world. If I have a criticism, it’s more about the script than this production – there are a lot of actors without much to do, and I think more could be made of the ensemble. I’m also not sure why Winston and Julia get married – that’s not in the book and it doesn’t seem like there’s any dramatic purpose for the change.

That aside, EUTC’s 1984 is remarkable from start to finish, with even the final bows making a statement. It’s double-plus good.

4.4 stars

Susan Singfield