21/02/22

King’s Theatre, Edinburgh

‘It’s just a jump to the left… and then a step to the righ-hi-hi-hight!’

It’s hard to believe that Richard O’Brien’s shlock-horror musical began its theatrical journey way back in 1973. Like many others, I didn’t actually witness it until The Rocky Horror Picture Show hit cinema screens in 1975. I can honestly say I’d never seen anything like it. The sexual politics were startling to say the least, Tim Curry’s Frank N Furter virtually burned up the screen, and yet the film didn’t make much of an impact at the box office. Go figure.

It wasn’t until much, MUCH later that it began to build its dedicated cult following.

Die-hard fans are only slightly in evidence at the King’s Theatre tonight, a few brave souls sporting French maid outfits, stockings and suspenders – which may have more to do with the Scottish weather than anything else. But the elderly couple sitting in front of me are clearly longtime fans, singing along with every single number and helping each other into the aisle to smash The Time Warp.

Rocky Horror is just a gloriously silly romp with canny sci-fi references, backed up by a whole string of banging songs. From the opening chords onwards, I’m hooked.

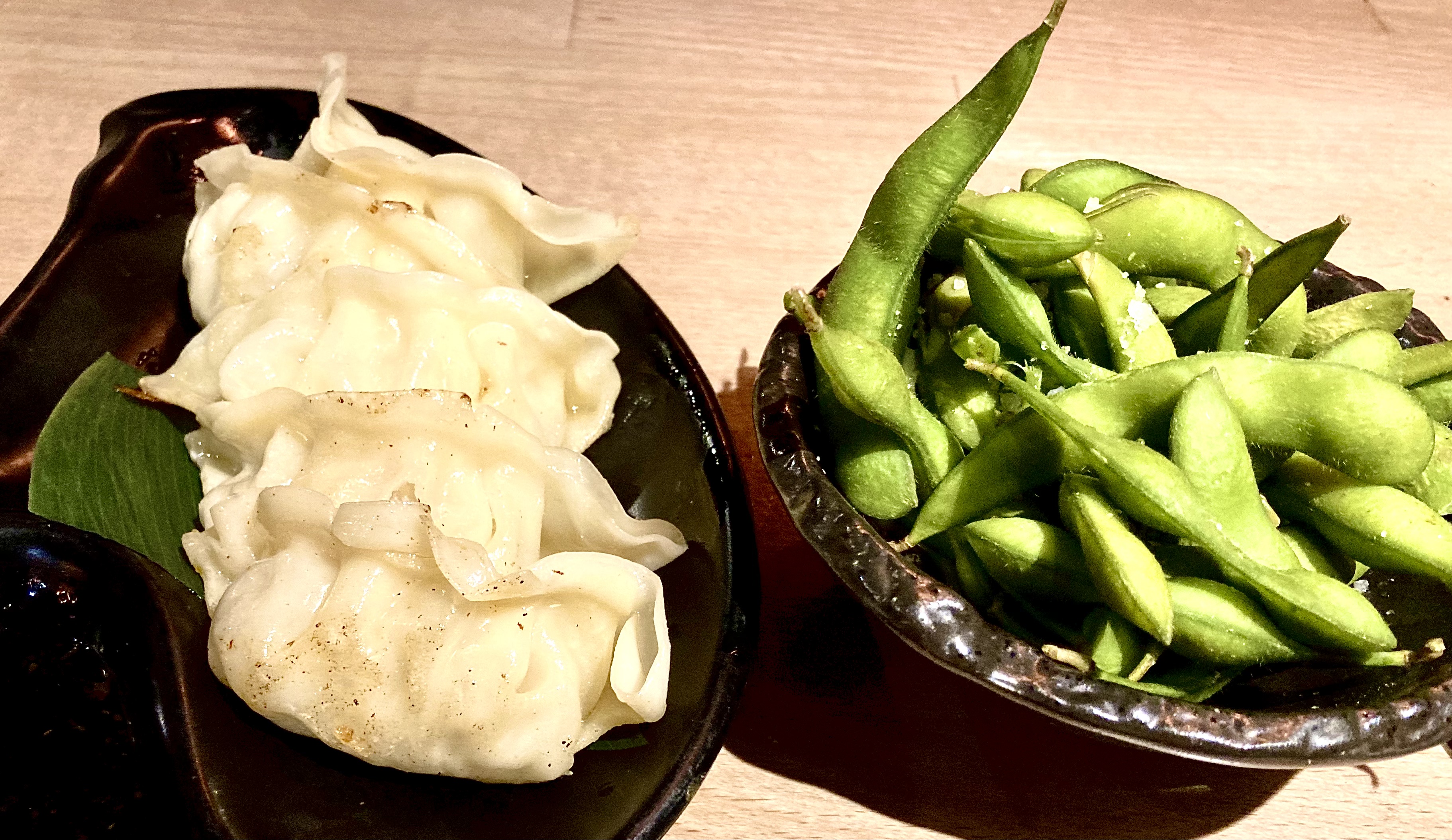

Brad (Ore Oduba) and Janet (Haley Flaherty) are two wholesome (okay, repressed) people, whose car breaks down one stormy night. They take refuge in that creepy-looking castle they passed a couple of miles back. Here they meet their unconventional host, Frank N Furter (Stephen Webb), his handyman, Riff Raff (Kristian Lavercombe), his maid Magenta (Suzie AcAdam) and a whole gaggle of deranged characters with a propensity for dissolute behaviour.

Furter, it transpires, has been working on a special project and Brad and Janet have arrived on the very night he plans to unveil Rocky (Ben Westhead), the perfect sexual companion.

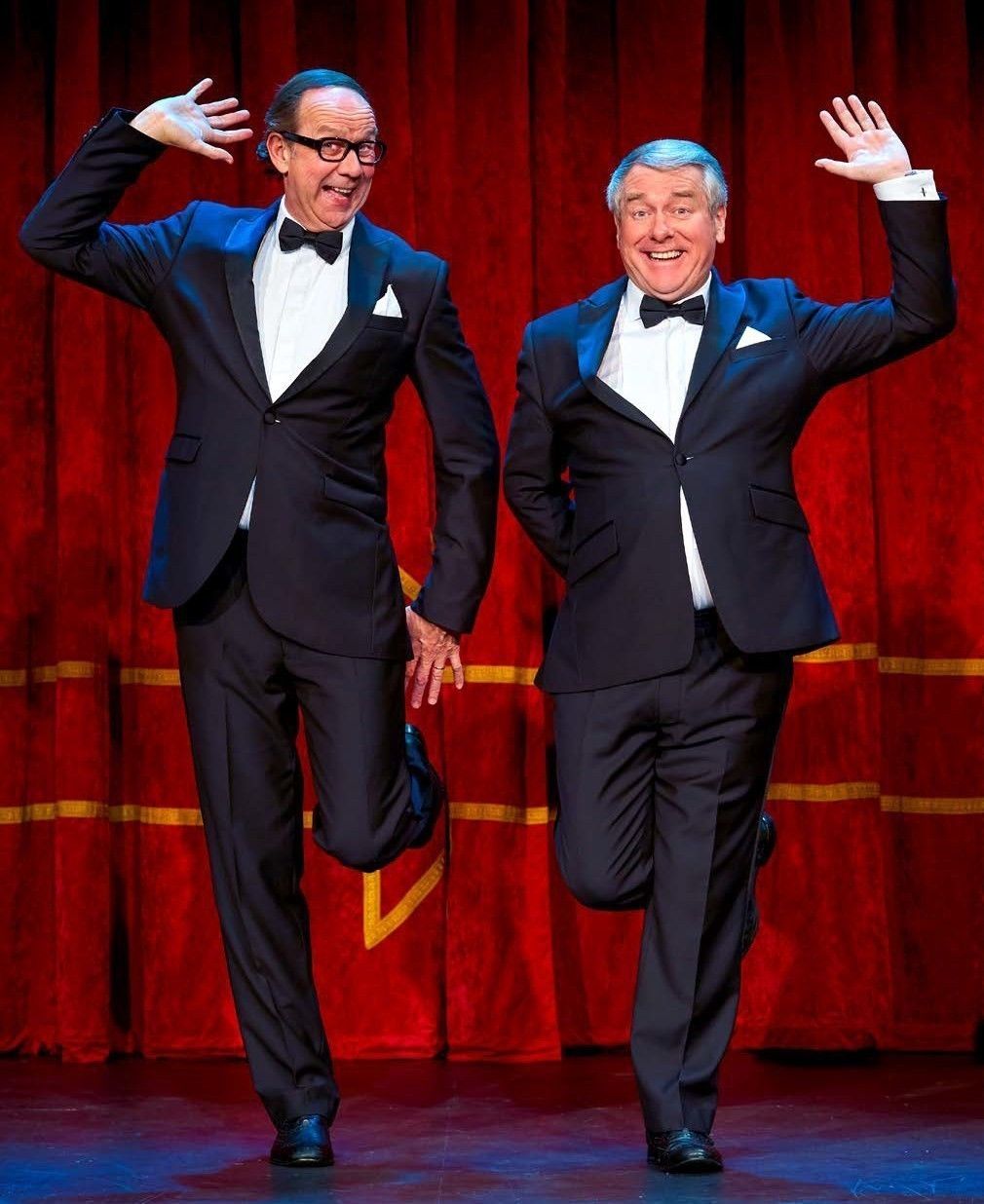

This production, directed by Christopher Luscombe, moves like the proverbial tiger on vaseline – the dance routines are brilliantly executed, Webb is wonderfully flamboyant as Furter and, of course, the presence of The Narrator (Philip Franks) is the production’s trump card. Suave, sophisticated and delightfully potty-mouthed, he fields interjections from the more vocal followers and offers a few pithy observations in return. One of them, about Prince Andrew, has the entire audience applauding.

Okay, so the first half still features the lion’s share of the best songs – which has always slightly unbalanced the production – and there are a couple of scenes in the second half that, viewed through a contemporary gaze do feel a bit… well, rapey… but of course, this was written at a time when the subject of sexual politics was in its infancy. O’ Brien’s main theme – that people should embrace and celebrate their sexual identities – still seems somehow ahead of the game forty-nine years after the show’s birth. And it seems highly unlikely that anybody is going to attempt an update this late in the game.

This is an absolute delight. As the performers thunder into a reprise of the show’s two best songs, the entire audience is up on its feet, clapping, dancing and singing along. Few nights out at the theatre are as deliriously enjoyable as this – and as we wander out into the night, we’re still humming The Time Warp.

After so long shut away in glum silence, we all deserve a large helping of Rocky. If this doesn’t put a great big stupid grin on your face, then nothing will.

4.6 stars

Philip Caveney