13/08/23

Summerhall (Main Hall), Edinburgh

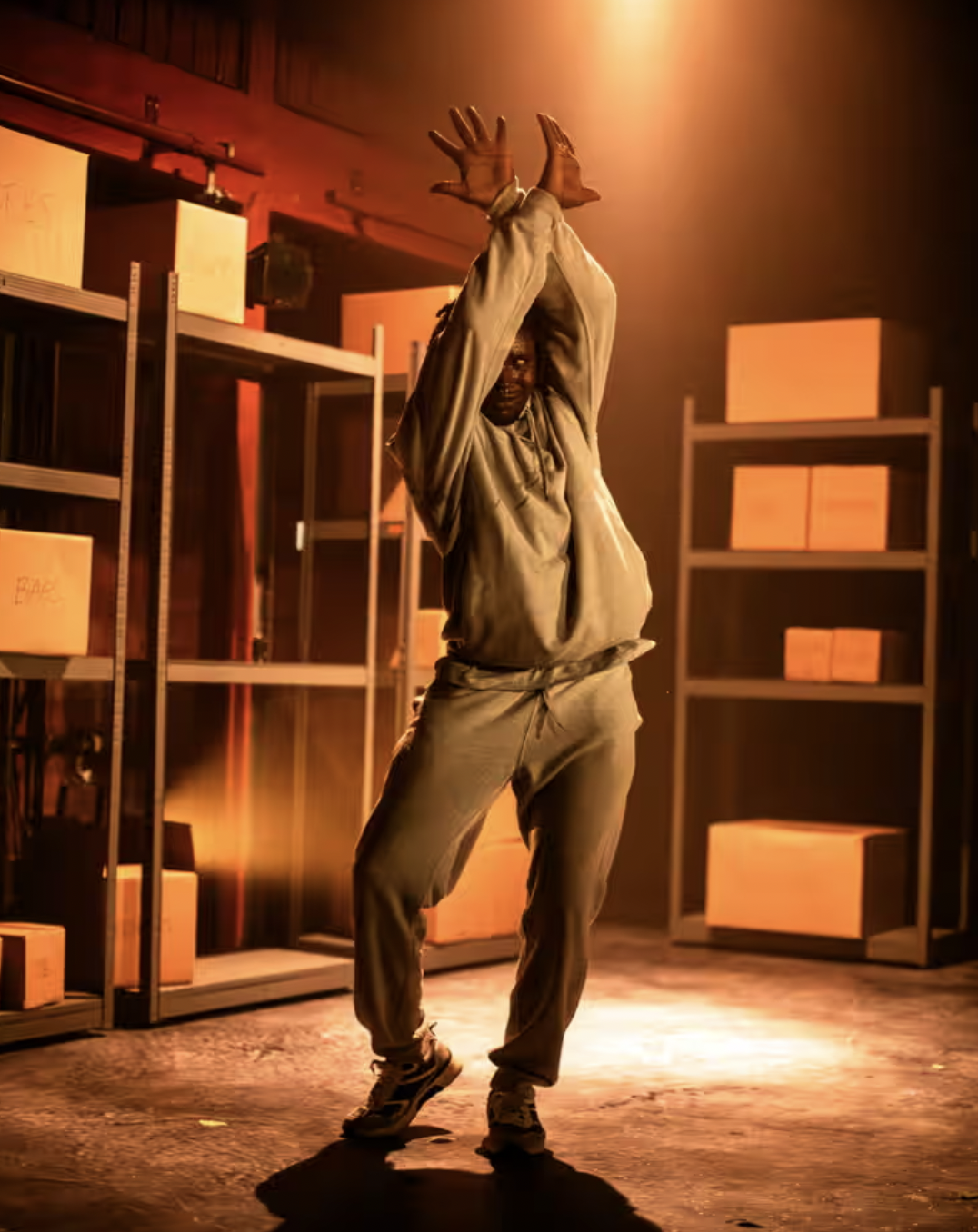

Lung is a verbatim theatre company, whose raisin d’être is to make hidden voices heard. “We use people’s real words to tell their stories; our shows always have a wider campaign and political aim.” In tonight’s show, those hidden voices belong to people failed by the UK prison system, specifically three young men who died in HMP Woodhill and the families who mourn them. It’s the first interpretative dance/verbatim mash-up I’ve ever seen, and it’s astonishingly powerful.

Recorded voices play over a soundscape by Sami El-Enany and Owen Crouch. Meanwhile, Chris Otim acts as the ghosts of the lost boys, and Tyler Brazao, Marina Climent and Miah Robinson play their relatives. Alexzandra Sarmiento’s choreography highlights the trauma inflicted on whole families by our punitive system, as they move like desperate Zombies through the years, reeling from blow after blow.

Director Matt Woodhead spent four years interviewing seventy people for this play – including inmates, prison officers, lawyers, and politicians, as well as the families featured here. The main focus is on three individuals – an urgent reminder that the awful statistics hide real people. Stephen Farrar, Kevin Scarlett and Chris Carpenter were all found dead in their cells at Woodhill. They all ostensibly took their own lives. But did they? “Woodhill killed them,” their families say. “The state killed them.”

The UK has the highest prison population in western Europe. Why? Do more than 83,000 of our people – more than 130 per 100k – really need to be locked up? Who benefits? Not the inmates, that’s for sure. And not wider society either – there is plenty of research proving prison doesn’t work. But private for-profit companies run prisons here, and they’re incentivised to lock people up, and incentivised to keep costs down once they’re inside. It shouldn’t come as a surprise that a recipe for disaster results in, well, disaster…

I get frustrated by our failure to look north: we have a model education system to look to in Finland, but we ignore it; likewise, Norway’s criminal justice system is a huge success: fewer people locked up (just 46 per 100k), low rates of recidivism, a compassionate prison culture based on rehabilitation. It’s kinder, cheaper and actually reduces crime. But still our politicians forge ahead with our failed revenge model, punishing people for being poor, for struggling with their mental health, for being Black.

Woodhill is relentless and startling, and there’s a moment, about fifteen minutes in, where I begin to feel restless, wanting a break from the dancing and recorded voices, perhaps some dialogue from the actors onstage. But I guess that’s the point: this is hard to bear, even as an audience member, even for an hour. And, of course, the fact that the actors never actually speak underscores how voiceless these people usually are. Woodhill offers them a rare chance to be heard.

Woodhead’s production, though unnervingly bleak, does offer a glimmer of hope. The piece is designed to educate, to change people’s minds. At the end, we are asked to sign a petition, to ensure that recommendations made at inquests – such as Stephen’s, Kevin’s and Chris’s – are implemented. It’s not enough, but it’s a start.

4.2 stars

Susan Singfield