21/01/22

Cineworld, Edinburgh

Kenneth Branagh’s semi-autobiographical film, Belfast, opens in supremely confident style.

We are presented with sleek, full-colour images of the city as it is now – the kind of scenes that might grace a corporate promotional video. And then the camera cranes up over a wall and, suddenly, we’re back in the summer of ’69, viewing events in starkly contrasting monochrome, as children run and play happily in the streets of humble terraced houses.

Amongst them is Buddy (Jude Hill), eight years old, wielding a wooden sword and a dustbin-lid shield. But the serenity of the scene is rudely disrupted by the arrival of a gang of masked men brandishing blazing torches and Molotov cocktails, extremist Protestants come to oust the Catholics who have dared to dwell on these streets. Buddy and his family are Protestant too and have happily lived alongside their Catholic neighbours for years, but now find themselves swept up in the ensuing violence.

It’s a powerful moment as we witness Buddy’s terror, the unexpected suddenness of this sea change literally freezing him in his tracks.

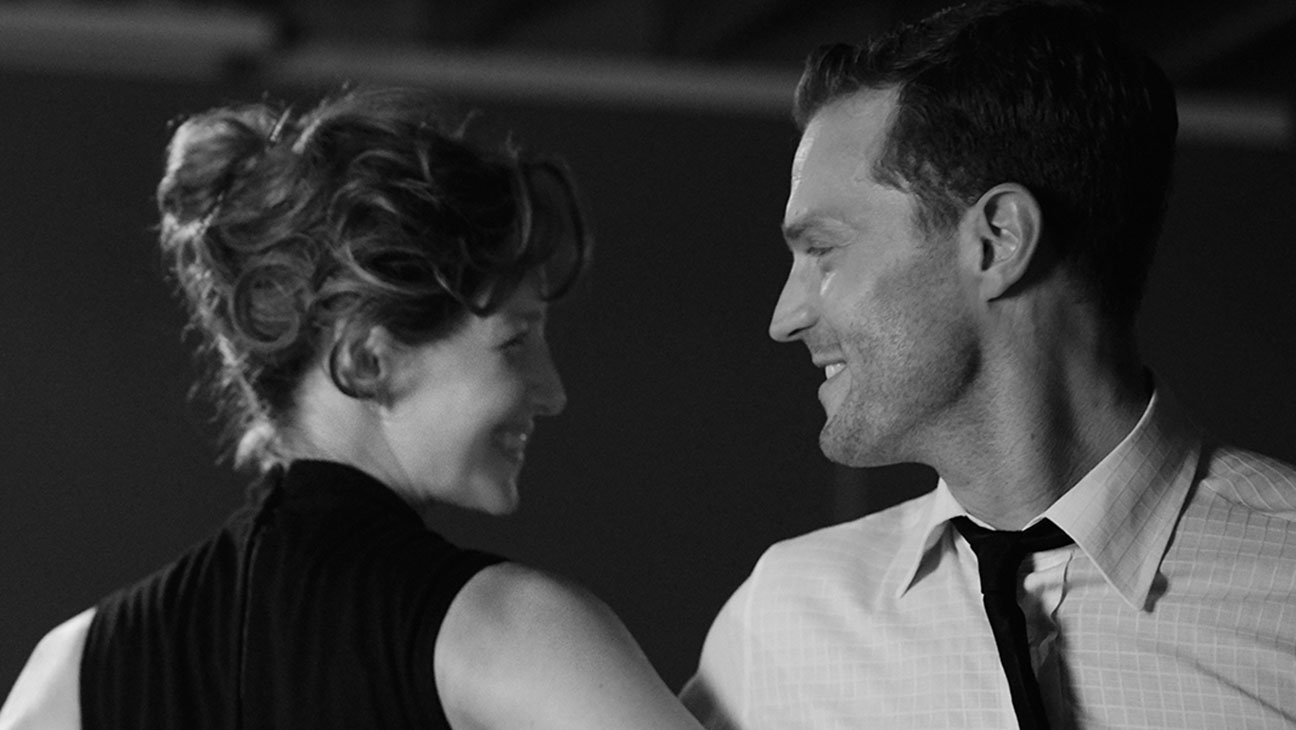

Then a gentler story begins to unfold, and we witness key events through Buddy’s naïve gaze. We are introduced to his Ma (Caitriona Balfe), to the father he idolises (Jamie Dornan), to his grandparents (Judi Dench and Ciarán Hands), and to the various neighbours and acquaintances who live in his familiar neighbourhood, a world he cherishes, suddenly transformed into something ugly and unpredictable.

Buddy’s father, a joiner by trade, works away from home in England, struggling to pay off his crushing tax debts. He’s keen to leave the city of his birth, to forge a new life for the family in England – but his wife is reluctant to leave and Buddy is obsessed with staying close to the girl at school he’s fallen in love with and hopes to marry one day.

Besides, how could he even think of leaving his beloved grandparents behind?

Branagh writes and directs here and handles both crafts with consummate skill, walking with ease the perilous tightrope between affection and sentimentality. Happily, he rarely puts a foot wrong. Buddy’s formative experiences include a visit to the theatre to see A Christmas Carol (with a lovely final performance from John Sessions – to whom the film is dedicated) and regular forays to the cinema, where we see extracts from Westerns High Noon and The Man Who Killed Liberty Valance. (If a cinema showing of One Million Years BC doesn’t exactly tie-in with the year in which the film is set, well no matter. Buddy is an unreliable narrator and his memories are built on uncertain foundations.)

I love Belfast. It’s a classy production, from the vintage Van Morrison soundtrack to the brilliant performances from the supporting cast. Young Jude Hill is simply perfect as Buddy, offering up a range of emotions that challenge the abilities of veteran performers Dench and Hinds. Watch out for some delicious Easter eggs that point to Branagh’s destiny. This film is all about formative experiences, the kind that shape a young boy’s future forever.

Belfast is an absolute joy, ready to be sampled at cinemas across the UK.

4.6 stars

Philip Caveney