10/03/24

Cineworld, Edinburgh

Origin isn’t like any film I’ve seen before. Structurally, it’s akin to a dramatised lecture – but if that sounds dry, then I’m doing it a huge disservice. Writer/director Ava DuVernay has taken an academic text and created an artist’s impression of both the work and its author. The result is multi-layered: at once instructive and provocative – and absolutely riveting.

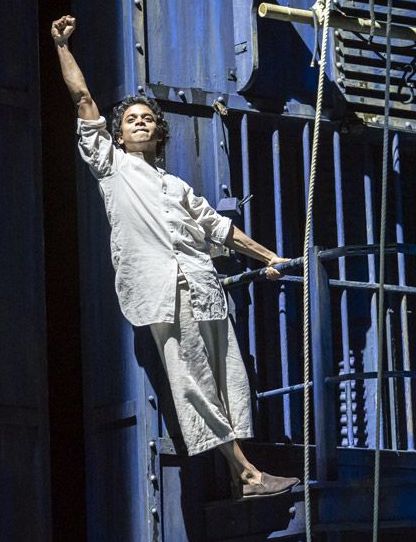

Based on Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents by Isabel Wilkerson (played here by Aunjanue Ellis-Taylor), Origin isn’t an easy watch. Wilkerson’s central conceit is that all oppression is linked – that the Holocaust, US slavery and India’s caste system all stem from the same fundamental practice of labelling one group of people ‘inferior’. This perception is entrenched via eight ‘pillars’, including endogamy, dehumanisation and heritability. DuVernay has done a sterling job of distilling these complex ideas and making them accessible, but the volume of cruelty on display is devastating. Who are we? Why do we keep on letting this happen? Some scenes are particularly heartbreaking, for example the young Al Bright (Lennox Simms)’s humiliating experience at a swimming pool in 1951, and I can hardly bear to mention the visceral horror of seeing people crammed into slave ships.

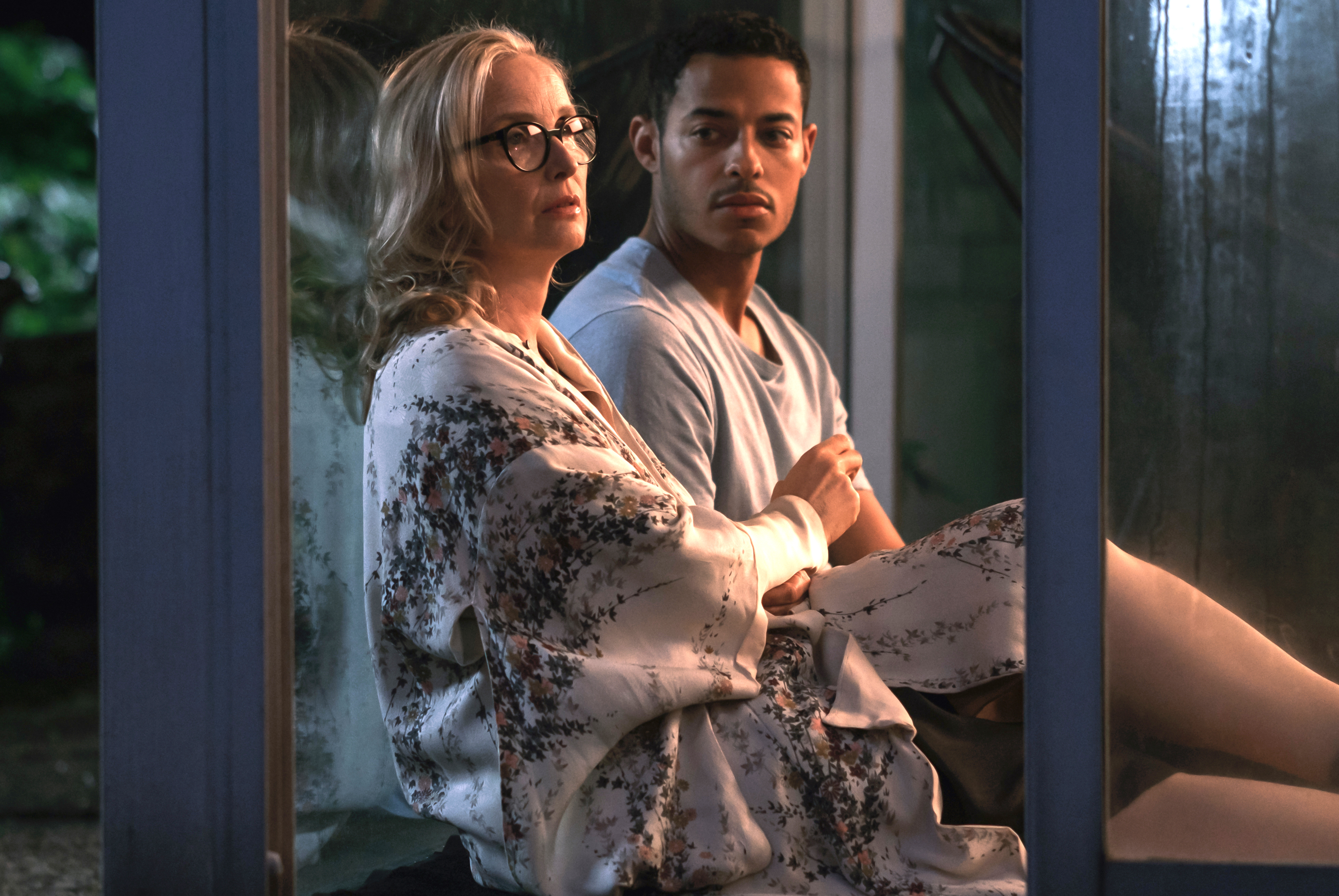

Ellis-Taylor’s Wilkerson is very engaging. She’s not only fiercely intelligent, but also thoughtful and gentle. Despite the weighty topics that dominate her working life, she finds time to have fun with her husband, Brett (Jon Bernthal), and to look after her mum, Ruby (Emily Yancy). She feels real.

Wilkerson’s personal life anchors the movie, which begins with her looking at retirement homes with Ruby. We see how Trayvon Martin (Myles Frost)’s shooting sows the first seed of her thesis, and then we jump back and forth in time and place, bearing witness to Nazi book burnings and Bhimrao Ambedkar’s ‘untouchable’ status; to Elizabeth and Allison Davis’s undercover work with Burleigh and Mary Gardner, documenting the everyday realities of racism in 1940s Mississippi. It is to DuVernay’s credit that we are never in any doubt about where we are or what point is being made.

There are moments when the concepts need bullet-pointing for clarity, and this is neatly achieved by the addition of a literal whiteboard. We see Wilkerson laboriously erecting it, before covering it in notes about the pillars that hold oppression in its place. This helps to anchor the key arguments, making them easy to grasp and remember.

Origin is a demanding piece of cinema, but it’s worth the effort. I come away feeling both horrified and educated, looking at the world in a different way.

4 stars

Susan Singfield