02/10/25

Traverse Theatre, Edinburgh

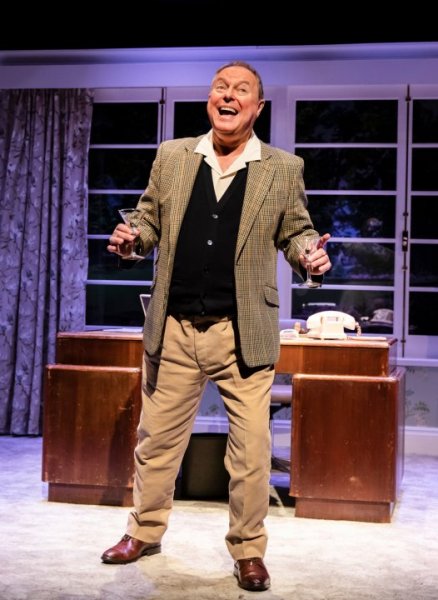

High school can be a minefield for some students, as Her (Eleanor McMahon) discovers when partially- clothed photographs of her start to appear on social media and are gleefully shared around her class, fuelling heartless gossip and ill-founded assessments of her character.

But who is to blame? Is it her so-called boyfriend, Ryan, who took the photos without her consent? Is it his friends, who shared them without his? Is it Him (Reno Cole), the boy she grew up alongside and who has always seemed so supportive but doesn’t stand up for her now? She knows that he has problems at home and that he sometimes struggles with his own issues, but how could he let her down like this?

Meanwhile, B1 (Zara-Louise Kennedy) and B2 (Alex Tait) are always on hand to analyse things, making snarky, acerbic observations like some kind of teenage Greek chorus, moving swiftly from role to role as they deliver their characters’ different reactions to the situation.

Strange Town’s tightly-structured production, written by Jennifer Adam and directed by Steve Small, is an object lesson in how to deliver a polemic and should be required viewing for teenagers across the land. Tight, propulsive and perfectly-pitched, its anchored by excellent performances by its four young actors, the serious message punctuated (but never diluted) by the quirky witticisms expertly delivered by Kennedy and Tait.

In the age of social media, moral lines can sometimes seem blurred, but Her sets out its premise with absolute clarity. As the show embarks on its third tour, its message seems more relevant than ever – and, while it’s clearly aimed at young audiences, it’s a production that speaks to people of all ages.

4.5 stars

Philip Caveney