10/01/26

Cineworld, Edinburgh

There is a tide in the affairs of [wo]men, which taken at the flood, leads on to fortune – and the confluence of Maggie O’Farrell, Chloé Zhao and Jessie Buckley exemplifies this theory. All three are at the pinnacles of their respective professions and their combined talents make for a flawless film. Hamnet is artfully crafted and beautifully realised, a privilege to watch.

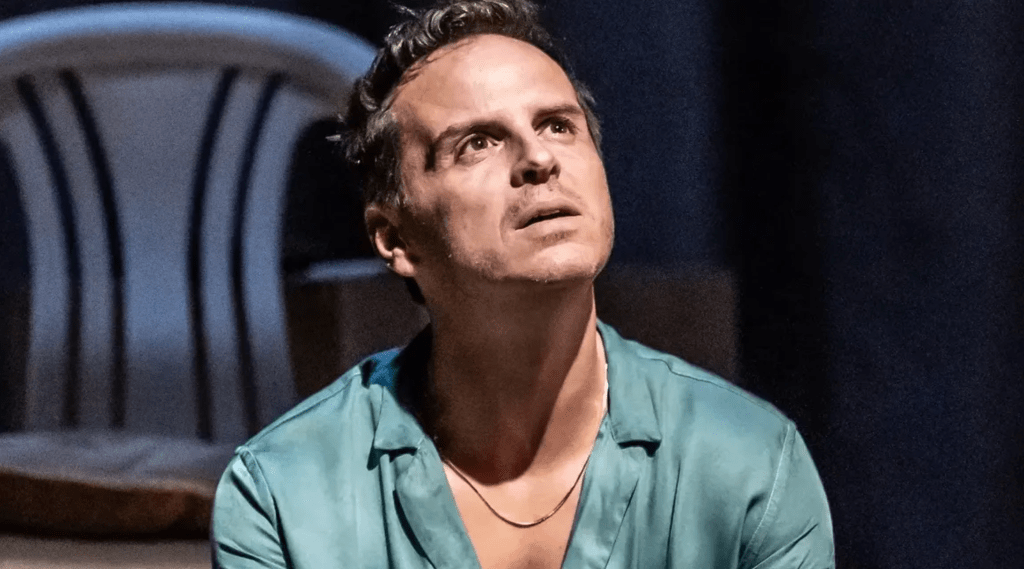

Adapted by O’Farrell and Zhao from the former’s critically-acclaimed novel, Hamnet stars Jessie Buckley as Agnes, more commonly known as Anne Hathaway or, let’s be honest, “Shakespeare’s wife”. Here, she is reimagined as a kind of woman-of-the-woods, her deep connection to nature a central tenet of her character. Her nephews’ Latin tutor, William (Paul Mescal), is beguiled by her, and – before long – they are pledging their commitment to one another in a secret ‘hand-fasting’ ceremony. Their families are horrified when Agnes falls pregnant, and only reluctantly agree to making their marriage official.

Agnes and William don’t care: they are deeply in love and adore their three children, Susannah (Bodhi Rae Breathnach), Judith (Olivia Lynes) and Hamnet (Jacobi Jupe). But that doesn’t mean it’s all plain sailing. While William can’t bear the confines of country life, Agnes knows she couldn’t survive in the city, away from the natural world. William doesn’t want to become a glove-maker like his father; he’s driven: he needs to write, to tell stories, to make his mark in the capital. Agnes realises there’s only one option, and tells him to go, to seek his fortune on the London stage, while she and the children remain in Stratford.

And so William departs for a double life with his wife’s blessing, at once successful playwright and loving family man. Meanwhile, Agnes grows ever more concerned about Judith’s health, fretting over her premonition that she will have only two children when she dies. And when calamity comes, she has to deal with it alone…

Readers often worry about movie adaptations of their favourite books, but I don’t think anyone needs to be concerned about this one. With O’Farrell on board as co-writer, the screenplay complements the novel perfectly. Buckley is magnetic, the intensity of her performance drawing us deep into her heartbreak and recovery, turning Agnes into a living, breathing woman instead of a mere footnote in her husband’s history, a cast-aside irrelevance, mother of his children but inheritor only of his “second best bed”. Mescal is also well-cast as William, torn between his vocation and his love for Agnes, turning his own anguish into a dramatic memorial to his lost child.

Under Zhao’s direction, Hamnet moves at a dreamy pace, yet never feels slow or dull. Lukasz Zal’s cinematography captures the symbolic importance of the forest, both to Agnes and – by extension – Shakespeare’s plays, where it is a place of magic and transformation, simultaneously dangerous and healing. The colour palette emphasises Agnes’s singularity, her red dresses distinctive in a sea of brown and green and grey. In her own way, she is every bit as extraordinary as William.

The three children play their parts well, and props to Nina Gold for casting Jupe’s real-life brother Noah as Hamnet’s fictional counterpart in the original Globe Theatre production of Hamlet. Their likeness adds to the cathartic effect of the performance, underscoring Agnes’s realisation that this is William’s theatrical expression of his grief. This final section is also a hymn to the shared experience of live theatre, the way plays can touch their audiences made literal as Agnes reaches for the hand of the young actor so reminiscent of her son, inspiring those around her to do the same.

Flawless from start to finish, Hamnet is an unmissable film, fully deserving of its Oscar nominations, and certainly worth a trip to the cinema to see it on the big screen.

5 stars

Susan Singfield