15/03/25

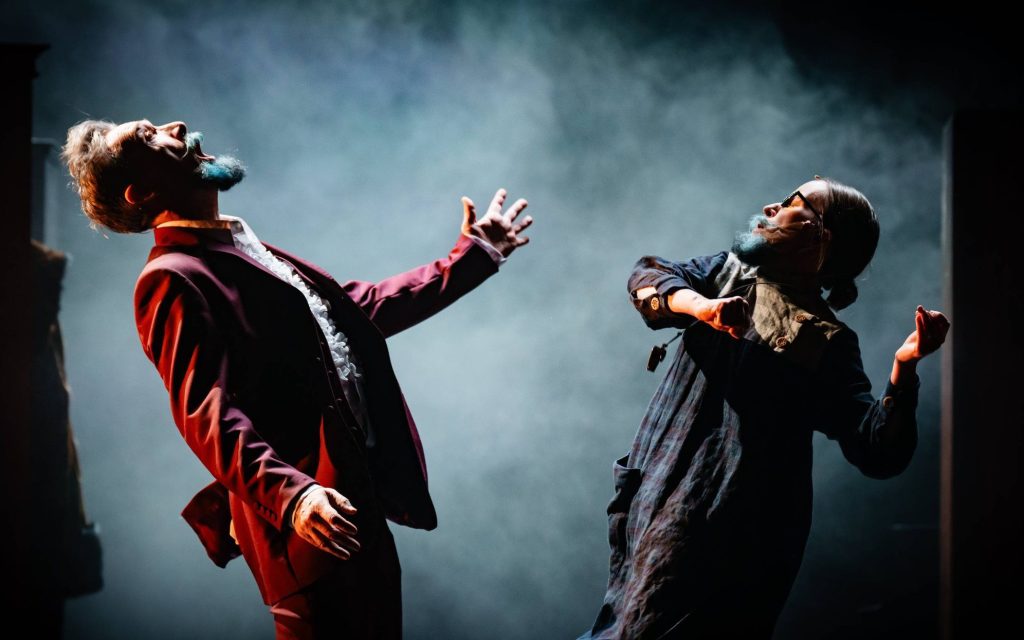

Traverse Theatre, Edinburgh

Felicity Ward’s manic energy is apparent from the moment we hear her shrieking, “Please welcome to the stage…” from the wings. She bounds on – which is in itself quite a feat, given the towering stilettos she’s wearing. And the tone is set for two hours of mayhem…

Ward is an experienced performer and it shows. The London-dwelling Aussie hasn’t done any stand-up for several months, she tells us, so why not “ease” back into it with a two-hour set? Actually, the show is a little baggy in places – I think I’d prefer a tight ninety minutes – but she has us in the palm of her hand and the Traverse 2 is rocking with laughter.

The subject matter is wide-ranging, from childbirth to the pandemic, from Quorn to, erm… fingering. There are also some weirdly wonderful animal impressions (more of these, please!), as well as some admirably frank references to mental health problems, particularly of the post-natal variety. Ward’s unfiltered openness is what makes her so engaging – well, that and her irrepressible mischievousness. She has an infectious laugh and the cheekiest smile you’ve ever seen.

I’m not usually a massive fan of comedians talking about parenthood because they mostly tread the same old ground, but Ward’s disarming admissions are bold and fresh. She makes us feel the horror of childbirth as well as the wonder; makes us laugh out loud (with schadenfreude) at her various mishaps.

I’m less keen on her weight-gain material. Previously a size 4, Ward bemoans “ballooning” to a size 14. While she aims for body positivity, claiming to love her belly, she also acknowledges that this material doesn’t really work now that she’s lost a lot of the weight, thanks to training for Australia’s Dancing With the Stars. It’s all a bit Bridget Jones and I’m not sure it ever would have sat well with me, especially as lines like, “When your leggings don’t fit, you know you’ve got a problem” and, “At least you’re never too big for a scarf” belie her supposed fat acceptance.

That aside, I have a thoroughly fabulous evening. Ward’s not lying with her titular assertion: she is exhausting. Her ADHD might be undiagnosed but it’s surely undeniable. She ping-pongs all over the place, physically and verbally – yet somehow manages to take us with her.

One thing’s for sure: I’ll be streaming the Australian version of The Office tonight. I can’t wait to see what this kinetic woman brings to the David Brent role. Meanwhile, I’ve laughed more than I have in ages. And I’ll never look at a giraffe in the same way again…

4.2 stars

Susan Singfield