07/09/25

Cineworld, Edinburgh

What Suzie (Miller) Did Next was bound to garner a lot of attention. The mega-success of Prima Facie, starring the inimitable Jodie Comer, has catapulted the Aussie playwright into the limelight, and left the theatre world waiting with baited breath to see what else she has up her silk sleeve.

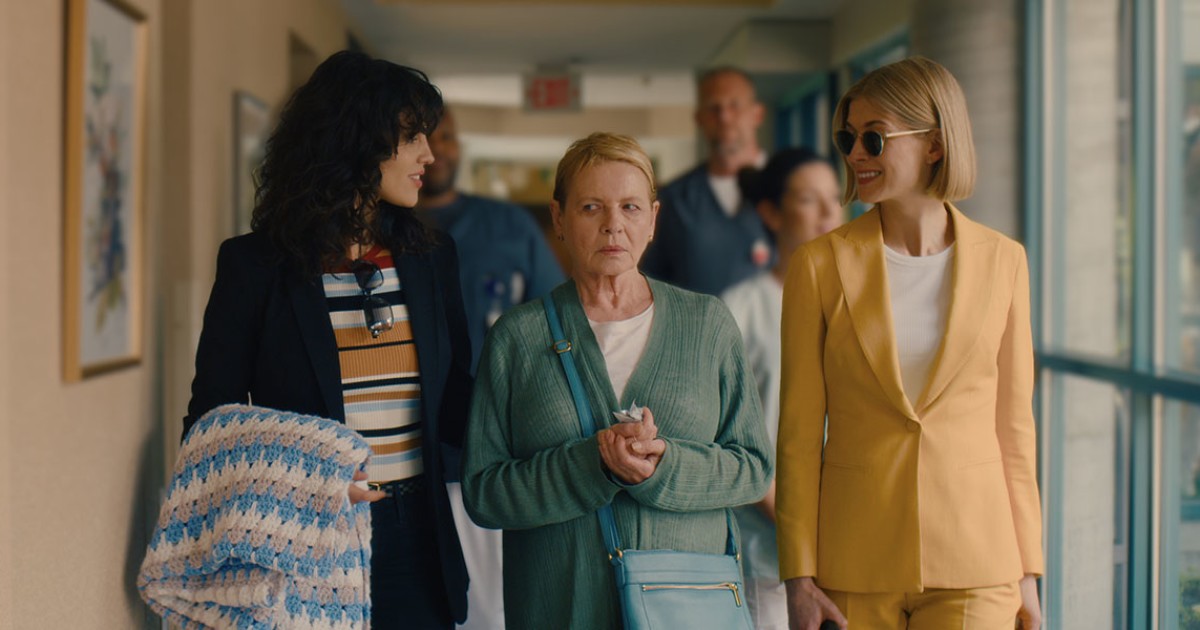

Inter Alia, a three-hander starring Rosamund Pike, serves as a kind of companion piece to the 2019 monologue, this time examining the legal system’s response to sexual assault from the vantage point of the Bench. Pike plays Judge Jessica Parks, a high-flying professional, juggling work and family life. She’s got the drive and energy to give both her all, but there’s no escaping ‘mom guilt’, however feminist you are. Still, she and her barrister husband, Michael (Jamie Glover), seem to be managing well: their teenage son, Harry (Jasper Talbot), isn’t exactly happy – he doesn’t really fit in at school and is the victim of some mild bullying – but he’s generally okay, mooching through his days and studying for A levels. He’s a gentle, sensitive boy, nothing like the entitled defendants Jess encounters in court, with their swaggering justifications for rape…

Until, one fateful night, when the ideals Jessica has long-espoused are suddenly called into question, along with her integrity. Who is to blame when a floundering young man commits a crime? And is it possible to be guilty and innocent at the same time?

Prima Facie‘s director, Justin Martin, is back on board for this follow-up polemic, and it’s just as gorgeously kinetic as the earlier piece, perfectly encapsulating the frantic nature of Jess’s life as she hurtles from conviction to kitchen, from case files to karaoke. The set, designed by Miriam Buether, is ingenious, a combination of the domestic and the professional, with props, costumes and doorways cunningly concealed in the kitchen units. At key moments, a wooded park is revealed beyond the dominant interiors, a glimpse into the outside world – both real and online – where Jessica isn’t in control, and which Harry has to learn to navigate for himself.

This is a gentler play than its predecessor, but no less audacious or thought-provoking. Pike is extraordinary in the lead role, and ably supported by her fellow actors. Miller doesn’t offer any easy answers or let anyone off the hook, but she expertly straddles the fine line between trying to understand assailants without diminishing their victims. Like those around us, we leave the cinema deep in discussion, trawling through our own experiences, trying to work out what we would do in Judge Jessica’s place.

I’m still not sure. But I do solemnly, sincerely and truly declare and affirm that Inter Alia is another searing commentary on our times, and – as such – another must-see from the National Theatre.

5 stars

Susan Singfield