15/01/2026

Cineworld, Edinburgh

The ’28 Years’ trilogy moves confidently into its second act, with Danny Boyle handing the directorial reins to Nia DaCosta. She rises to the challenge with her customary zeal and delivers a film that, for my money, comes close to equalling its predecessor. This time out there’s less emphasis on the blood and mayhem and more on the interplay between characters. Gore-hounds may complain they’ve been short-changed but, ironically, there’s still enough spine-ripping and brain-munching to ensure that this episode earns itself an 18 certificate. Young actor Alfie Williams is, once again, unable to officially attend the film’s premiere. (He was thirteen for the last one’s 15 classification.)

Did he get a private viewing? I hope so.

We pick up pretty much where we left off with Alfie (Williams) now a captive of ‘The Jimmys,’ the track-suited, blonde-bewigged followers of Sir Lord Jimmy Crystal (a malevolent Jack O’Connell, sporting a pretty convincing Scottish accent). Alfie soon learns that, if he wishes to remain alive, he’s going to have to fight for his place in the gang and, once a member, somehow embrace the heinous cruelty that Crystal likes to inflict on anyone he encounters – including, if the mood takes him, his own followers. Luckily, one of the gang, Jimmy Ink (Erin Kellyman), seems to have taken a sisterly shine to Alfie.

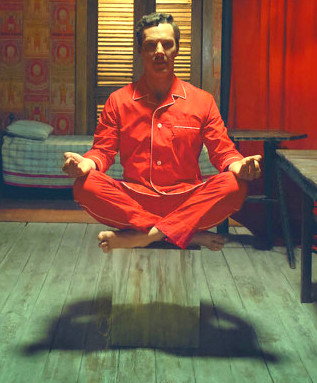

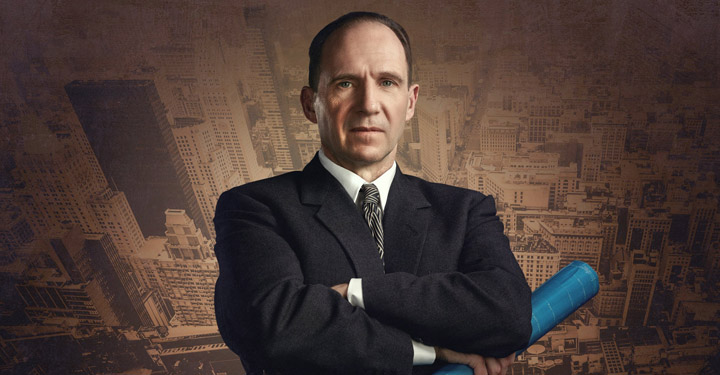

Meanwhile, Dr Ian Kelson (Ralph Fiennes) continues his gruesome work in the titular temple, with particular emphasis on trying to develop his growing ‘friendship’ with Samson (Chi Lewis-Parry), an infected Alpha. Kelson is attempting to tame the angry giant with regular doses of morphine, applied via a strategically-aimed blowpipe. Could it be that these experiments are leading Kelson tantalisingly closer to finding a cure for the deadly infection that has overtaken the world? More bafflingly, why is he listening to so much Duran Duran?

If the two main story strands are frankly bonkers, they nonetheless make for riveting viewing. DaCosta’s strong visual style combines with Alex Garland’s storytelling and the powerful music of Hildur Guǒnadóttir, to exert an almost hypnotic spell. There are kinetic action sequences, some astutely-handled flashbacks (Samson’s recollections of a childhood experience on a crowded train is particularly powerful), and Fiennes’ outrageous climactic dance routine, backed by Iron Maiden’s The Number of the Beast, is something I never expected to see – a slice of pure theatre writ large on a cinema screen. I also respond strongly to the film’s obsession with religion and the way that Kelson cleverly uses it to his own advantage.

And then, just when you think it’s all over, we’re treated to a short coda which neatly flips the whole concept back to its origins and reintroduces a character I had pretty much given up hope of ever seeing again – all of which ensures that I leave the cinema already looking forward to part three.

Job done. Bring it on.

4.6 stars

Philip Caveney