15/10/25

Lyceum Theatre, Edinburgh

Sometimes a particular production of a play can be a revelation. The Royal Lyceum’s The Seagull is a good case in point. Chekhov famously insisted that his plays were actually comedies – yet every time I’ve gone along to see one, I have been presented with something ponderous and rather miserable.

This inspired interpretation of the Russian’s best-known play, adapted by Mike Paulson, finally sets the record straight. While it’s indisputable that the story has a tragic conclusion, the journey there is spirited and so chock-full of acerbic humour that, from the opening lines, I’m laughing.

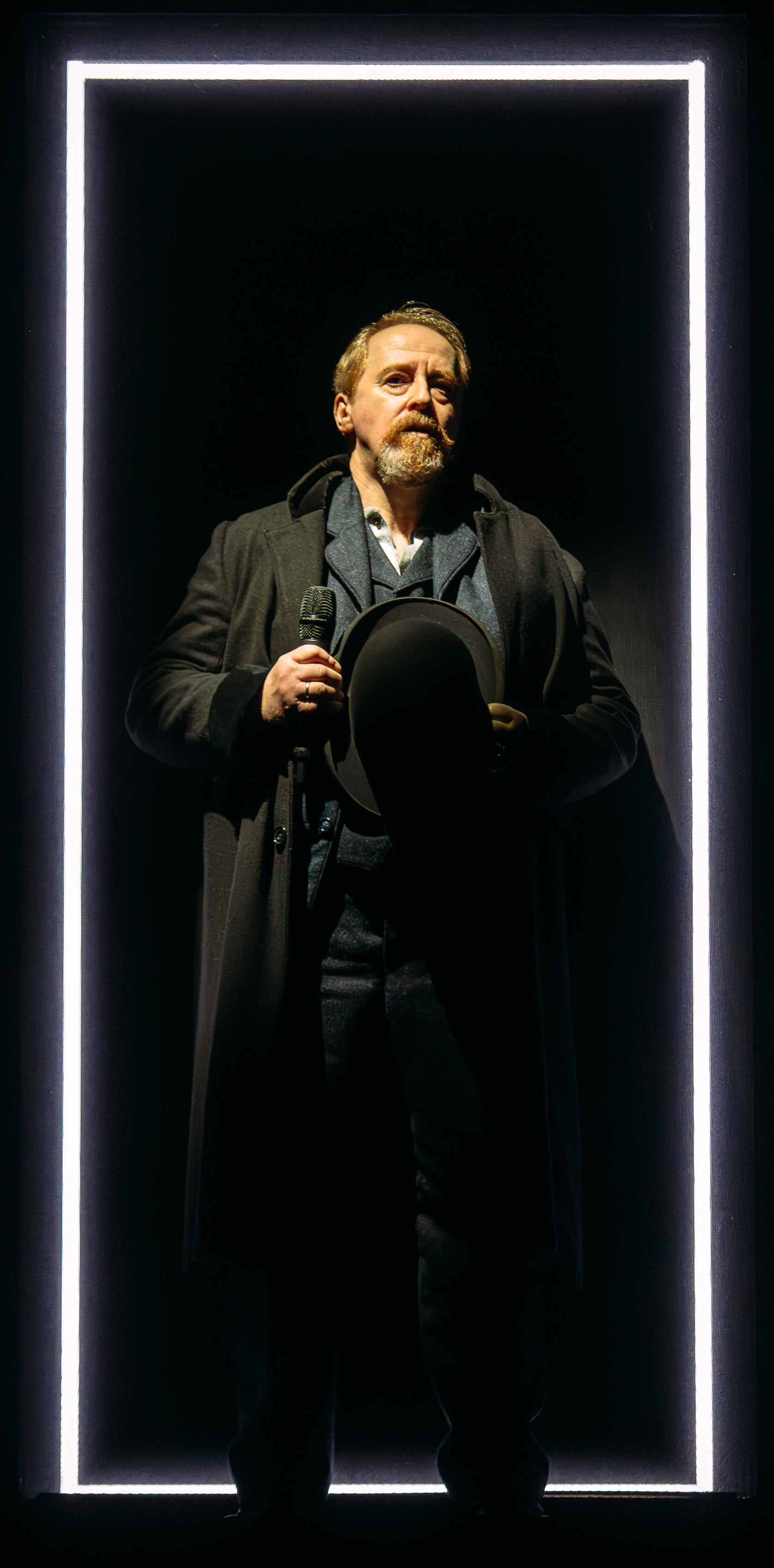

In the first act, the elderly and infirm Pyotr Sorin (John Bett) is entertaining his family and their friends at his country estate. His younger sister, former actress Irena Arkadina (Caroline Quentin), has brought along her son, Konstantin (Lorn McDonald), who is deeply in his mother’s thrall and has aspirations to be a playwright. Irena is also accompanied by her lover, Trigorin (Dyfan Dwyfor), a fêted young writer, though it’s clear he derives very little pleasure from his success.

Although unnerved by Trigorin’s presence, Konstantin presses ahead with a performance of his latest project. He’s enlisted the help of an aspiring actress, Nina (Harmony Rose-Bremner), who lives on a neighbouring estate. He claims to be seeking a ‘new theatrical form’ and he’s devastated when his mother airily dismisses the monologue as ‘incomprehensible.’ He’s even more upset when Nina (who he clearly adores) seems much more interested in talking to Trigorin than to him.

Meanwhile, Masha (Tallulah Greive), the daughter of the estate’s boorish steward, Shamrayev (Steven McNicholl), is hopelessly in love with Konstantin, though he seems barely aware of her existence. She views the fact that shy local schoolteacher, Medvendenko (Michael Dylan), is in love with her as something of a major irritation.

In such a tangle of unfulfilled longing, it’s inevitable that tragedy is waiting somewhere in the wings…

There’s so much to enjoy here and not just Quentin’s perfectly-judged performance as the conceited, self-aggrandising Irena, intent on making every conversation all about her. The gathering of disparate characters is well-realised, with Bremner excelling in the role of the increasingly-unsettled Nina, whose obsession with becoming an actress threatens to lead her headlong into madness. Dylan generates a goodly share of the laughs as the hapless and self-critical Medvendenko, in particular during his pithy exchanges with the local physician, Dr Dorn (Forbes Masson), who seems to have brought along enough laudanum to put everyone out of their misery.

I’m entranced by Anna Kelsey’s autumnal set design, particularly in the first act where Konstantin’s outdoor stage has an ethereal beauty. Director James Brining brings out all the nuances of Chekhov’s witty script and the piece seems to zip along, buoyed by what I assume is the simple intention of making this one of the most accessible Chekhovs you’re ever likely to see – an aim that is accomplished with élan.

4.5 stars

Philip Caveney