09/03/26

The Studio at Festival Theatre, Edinburgh

“Bloody Greek tragedies are like bloody buses,

You wait for several years,

And as soon as one approaches your local theatre,

Another one appears.”

(With apologies to Wendy Cope)

Hot on the heels of Medea at the Traverse comes The Bacchae at the Festival Theatre’s Studio, a striking solo version of Euripides’ compelling – and many-peopled – play. Written and performed by Company of Wolves’ artistic director Ewan Downie, this has been intelligently condensed from the sprawling original.

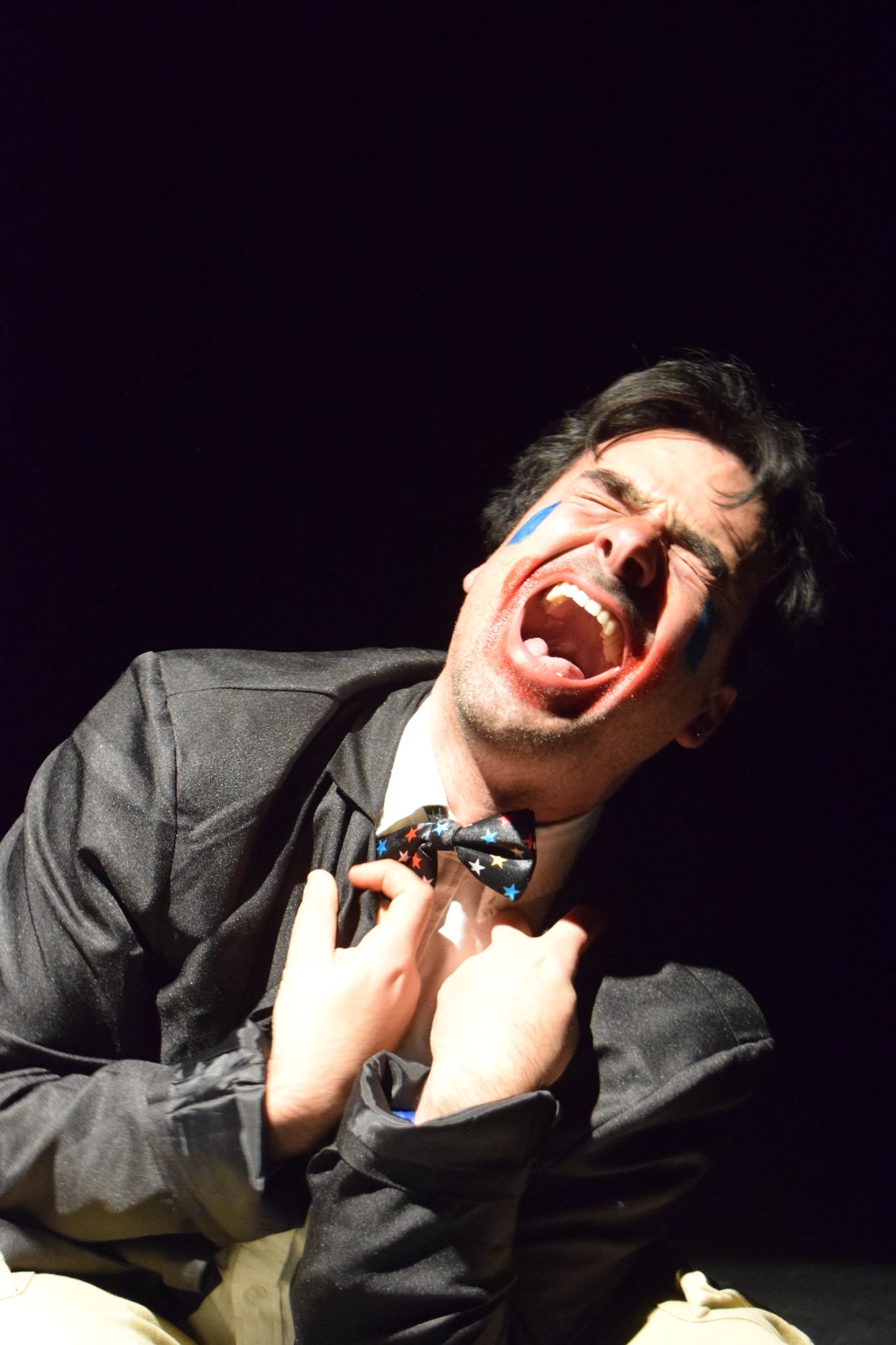

Downie is Dionysus, the god of change – a conceit that lends itself well to the multi-rolling necessary here. The son of Zeus and a mortal woman, Semele, Dionysus both narrates his own story and transforms into a raft of other characters, all perfectly distinct thanks to Downie’s precise physicalisation.

Employing Ancient Greek specialist, Dr Michael Carroll, as a creative consultant is a masterstroke, lending this radical interpretation a sense of authenticity. The narrative is typically convoluted. When the pregnant Semele dies at the sight of her lover, Zeus, in his divine form, the god seizes the embryonic Dionysus and gestates him in his thigh. Raising a baby isn’t on Zeus’s agenda though, so he tasks Semele’s sister, Agave, with parenting the boy. She obliges, but her own son, Pentheus, is understandably jealous of his half-god cousin. This resentment follows the men into adulthood, leading Pentheus, now King of Thebes, to forbid his people from worshipping the increasingly popular Dionysus, who preaches liberation from social restraints, encouraging his followers to indulge in frenzied, wine-fuelled rituals. Where else can their enmity lead but to murder?

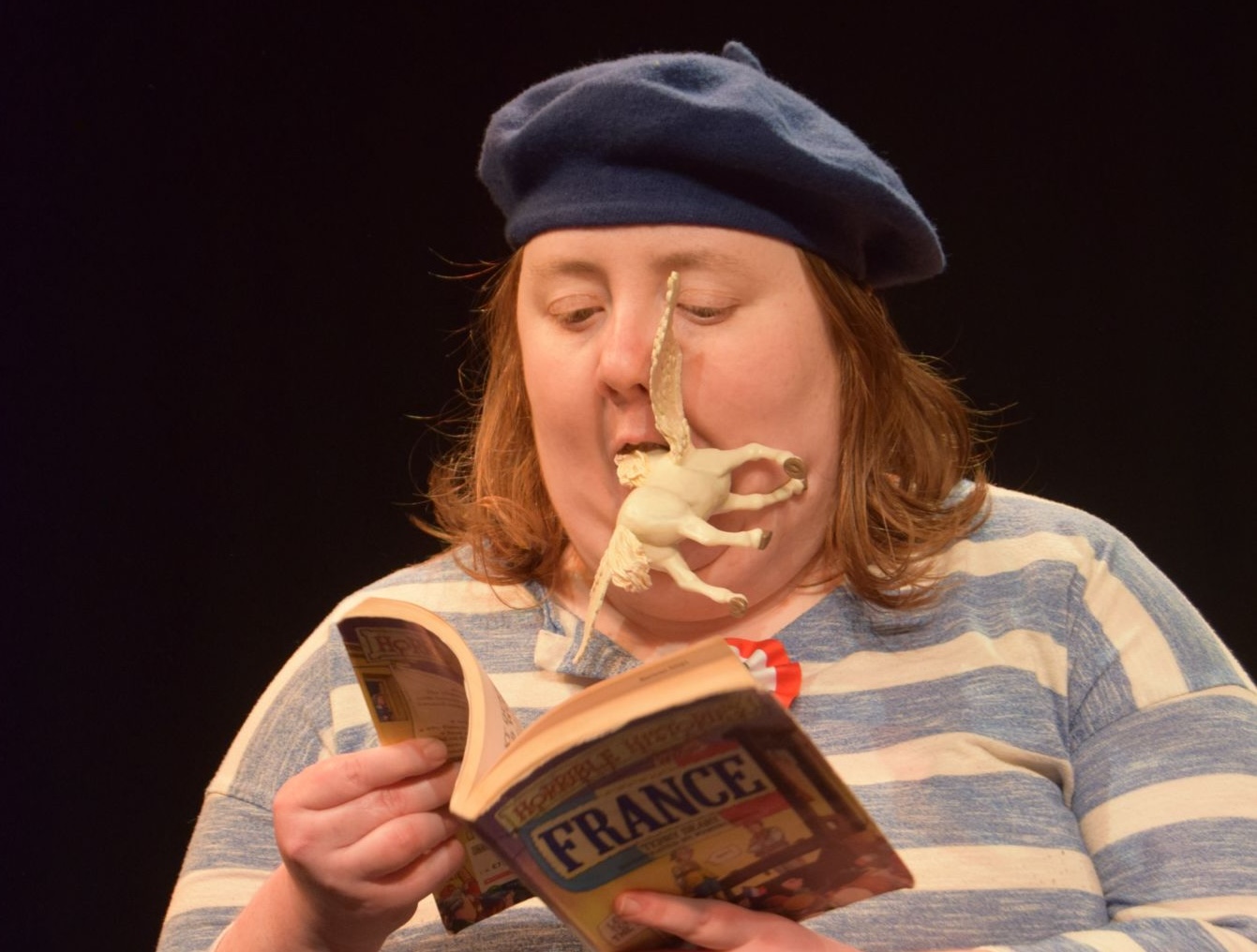

This is as much a piece of performance art as it is theatre: a visual spectacle set to poetry and song. Downie’s commitment is absolute, and it’s his sincerity and conviction that holds our attention. The contemporary set design (by Alisa Kalyanova) clashes with the millennia-old narrative, but I like this discordancy: it reflects the dissolution of boundaries highlighted by the queer subtext. The only off-note for me is the use of a plastic bottle of water. I’m sure there’s some reason behind the decision, but it looks pragmatic rather than intentional, unlike anything else on the stage.

Originally directed by the late Ian Spink and with Heather Knudsten now holding the reins, CoW’s The Bacchae is a fascinating, labyrinthine drama, anchored by an extraordinary central performance.

4 stars

Susan Singfield