10/08/24

Underbelly George Square (Wee Coo), Edinburgh

Tracey Emin… stereotype… train wreck. Oops! Sorry. Wrong notes. Let’s try again…

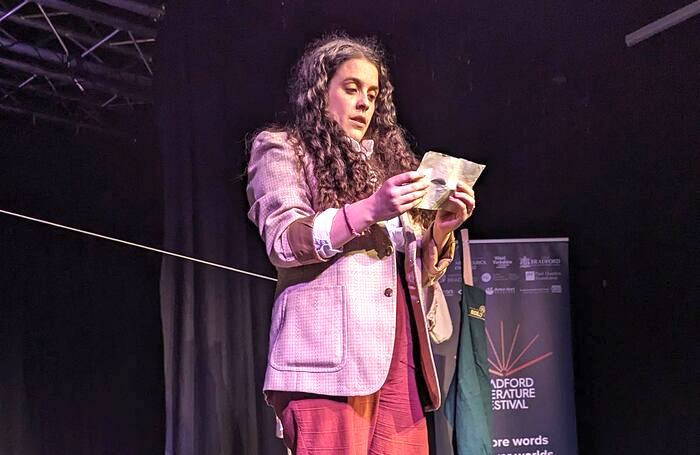

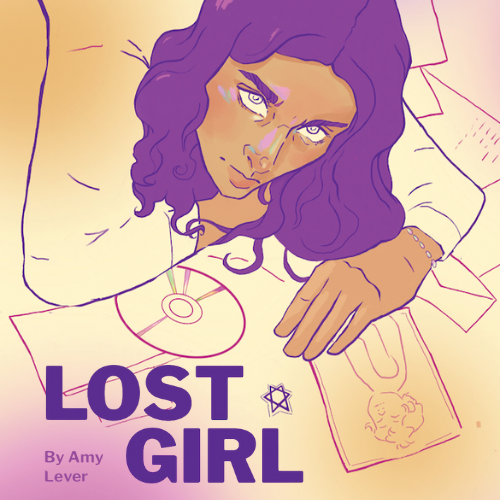

Amy Lever’s Lost Girl is a fascinating monologue, charting nineteen-year-old Birdy’s search for self-acceptance. She’s never been particularly clever (as her A level results confirm); she hasn’t any special talents and she doesn’t know what she wants to do with her life. Until now, none of this has really mattered, because she’s had her best friend Bex by her side, and they’ve been battling the world together. So what if Birdy didn’t make it into uni? Neither did Bex – or Jeremy Clarkson, for that matter – and they’re both doing okay.

But now Bex – resolutely Catholic – has unearthed some hitherto unknown Portuguese Jewish ancestry, which means she can claim an EU passport, and so she’s gone off travelling. Birdy, meanwhile, who is actually Jewish, has no such useful connections. “Hey, Siri,” she asks. “Is Syria in the EU?” Even Siri, who surely hears all sorts, isn’t programmed to deal with this level of ignorance. “Don’t be stupid,” he responds.

So Birdy feels lost. She’s plagued by recurring nightmares and angry with Bex for deserting her. She’s angry with her family too because… well, because they’re her family. Who else is going to bear the brunt of her frustration?

But when Birdy gets a job working in the archives of a local Jewish museum, she begins to unearth some secrets that make her see her relatives in a whole new light…

Lever is an accomplished actor, quickly earning our sympathy with her heartfelt performance. Her depiction of wannabe actor Bex’s disastrous one-woman show is very witty, as is her portrayal of the monosyllabic Sammy Morrison. The writing is good too, often causing us to laugh out loud, as well as giving us plenty to think about.

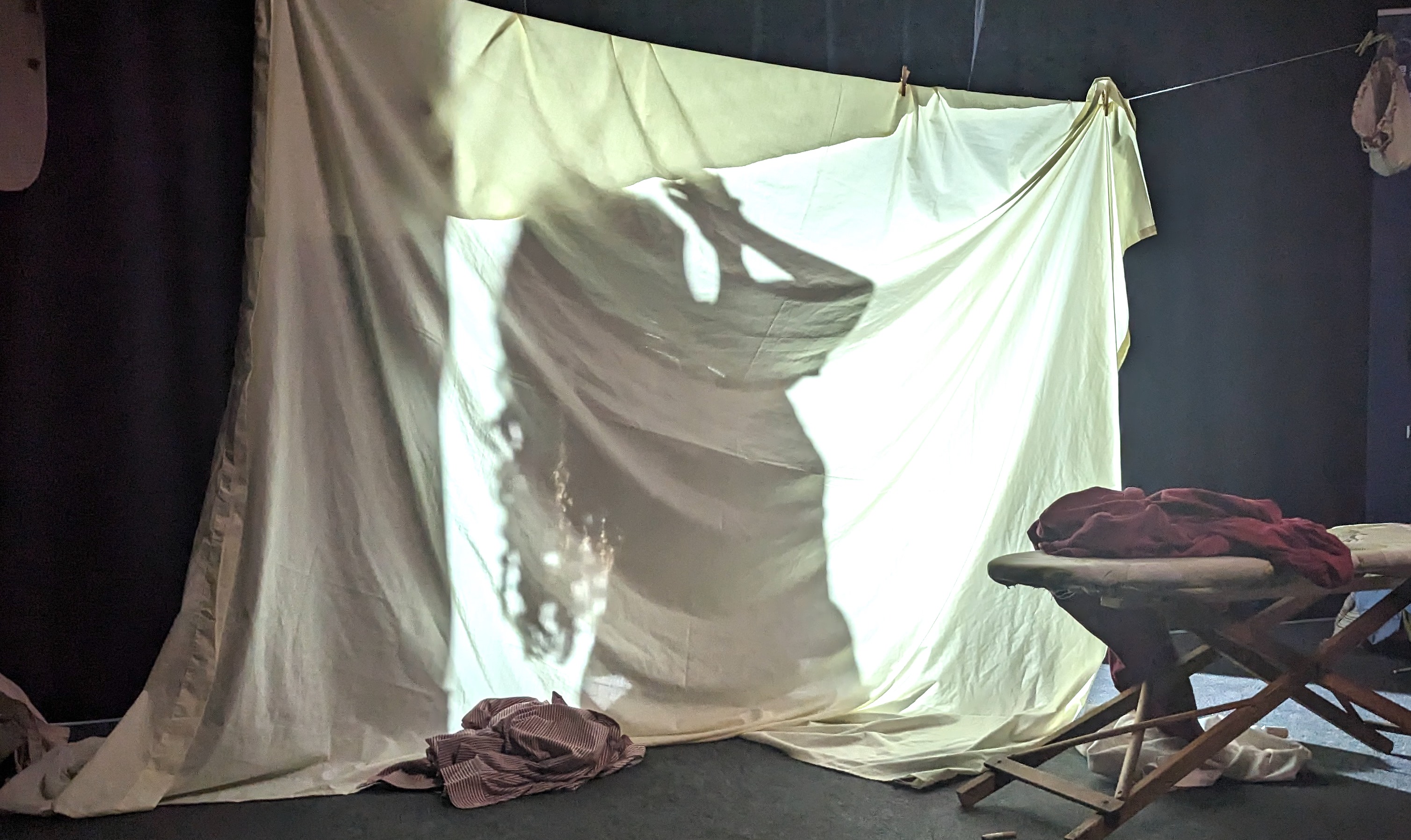

The simple, unfussy staging is well-suited to the piece, the frame of documents and photographs symbolising both cage and portal, illuminating Birdy’s contradictory impulses for stasis and for flight.

As much a character study as a play, Lost Girl offers a fascinating insight into the mind of a teenager seeking validation and coming to terms with her cultural identity.

4 stars

Susan Singfield