08/07/25

Update

In the aftermath of the bombshell dropped by Chloe Hadjimatheou in this weekend’s Observer, where she exposes the lies this story is based on, it feels right to reassess our original response to the movie. Our opening sentence included the words “raised eyebrows”. Perhaps we shouldn’t have been so gullible.

But we’re in good company, including Penguin Random House, Number 9 Films and more than two million readers worldwide. Chivalrous Jason Isaacs, sitting next to Raynor Winn on The One Show sofa, gently corrects her when she says it all began when she and her husband “got into a financial dispute”. “You were conned out of everything you had,” he says sympathetically. “You might not be able to say it but I can.”

The Winns’ audacity is breathtaking. According to Hadjimatheou, the real con-artist is Raynor, aka Sally Walker. Aka embezzler of £64k from her employer; aka borrower of £100k to pay back her ill-gotten gains and thus avoid a criminal trial. When their house was repossessed, it wasn’t because a good friend betrayed them; it wasn’t a naïve business investment gone wrong. It was the simple calling-in of an unpaid debt, ratified by the courts. Did Walker and her husband Ti-Moth-y really believe the truth would stay buried as they appeared on national television to publicise their untruths?

So how gullible were we, really? Like many, we believed the basic premise. Why wouldn’t we? Sure, it was clear that the exact circumstances of the couple’s slide into destitution were being glossed over, and of course their story was shaped into a neater narrative than real life provides. But we had no reason to doubt the fundamentals. (How could anyone have guessed they had a ‘spare’ property in France?) In fact, my interest piqued by the movie, I went on to read Winn’s books. I liked The Salt Path, although I was disappointed not to learn more about the calamitous investment. I found books two and three (The Wild Silence and Landlines) less interesting: just more of the same, but – now that the couple were housed and embracing successful careers – without the jeopardy. In these sequels, the focus shifts to Moth’s terminal illness, corticobasal degeneration, and the miraculous curative effect that hiking has for him. While the first book tentatively suggests that strenuous exercise might be beneficial for those with this rare condition, by the third we’re deep into dubious ‘wellness’ territory, with Winn’s ‘own research’ supposedly trumping anything a neurologist might purport to know.

Still, we won’t be taking down our review (you can read it in full below). We stand by it as a reaction to a well-acted and nicely-crafted film that we enjoyed. Of course, its message of grit in the face of adversity doesn’t have quite the same potency it did, now that we know the protagonists are a pair of grifters, but, if we can steel ourselves to view it as a work of fiction, it’s an affecting and moving piece.

Susan Singfield and Philip Caveney

01/06/25

Cineworld, Edinburgh

I’ve often remarked that real-life stories, depicted as fiction, would more often than not be the case for raised eyebrows. Take the case of Raynor and Moth Winn, for example: a married couple who, after a badly-judged business investment went tits up, found themselves evicted from their family farm, unable to obtain any financial help, bar a paltry £40 a week benefit. Around the same time, Moth was diagnosed with a rare (and inoperable) degenerative brain condition. Their response? To set off to walk the South West Coastal Path, a trip of hundreds of miles, telling themselves that if they just kept walking, something was sure to turn up…

Okay, so in a move they could surely never have anticipated, the book that Raynor wrote about the experience eventually went on to sell two million copies… but it would be a hard-hearted reviewer who begrudged them this success.

In this adaptation by Rebecca Lenkiewicz, we first encounter Raynor (Gillian Anderson) and Moth (Jason Isaacs) as they fight to save their last real possession – a small tent – from the ravages of the incoming tide. The couples’ back story is told in a series of fragmentary flashbacks, though director Marianne Elliott is less interested in the events that brought the couple to this sorry situation, than exploring the possibilities of what their newfound freedom brings them.

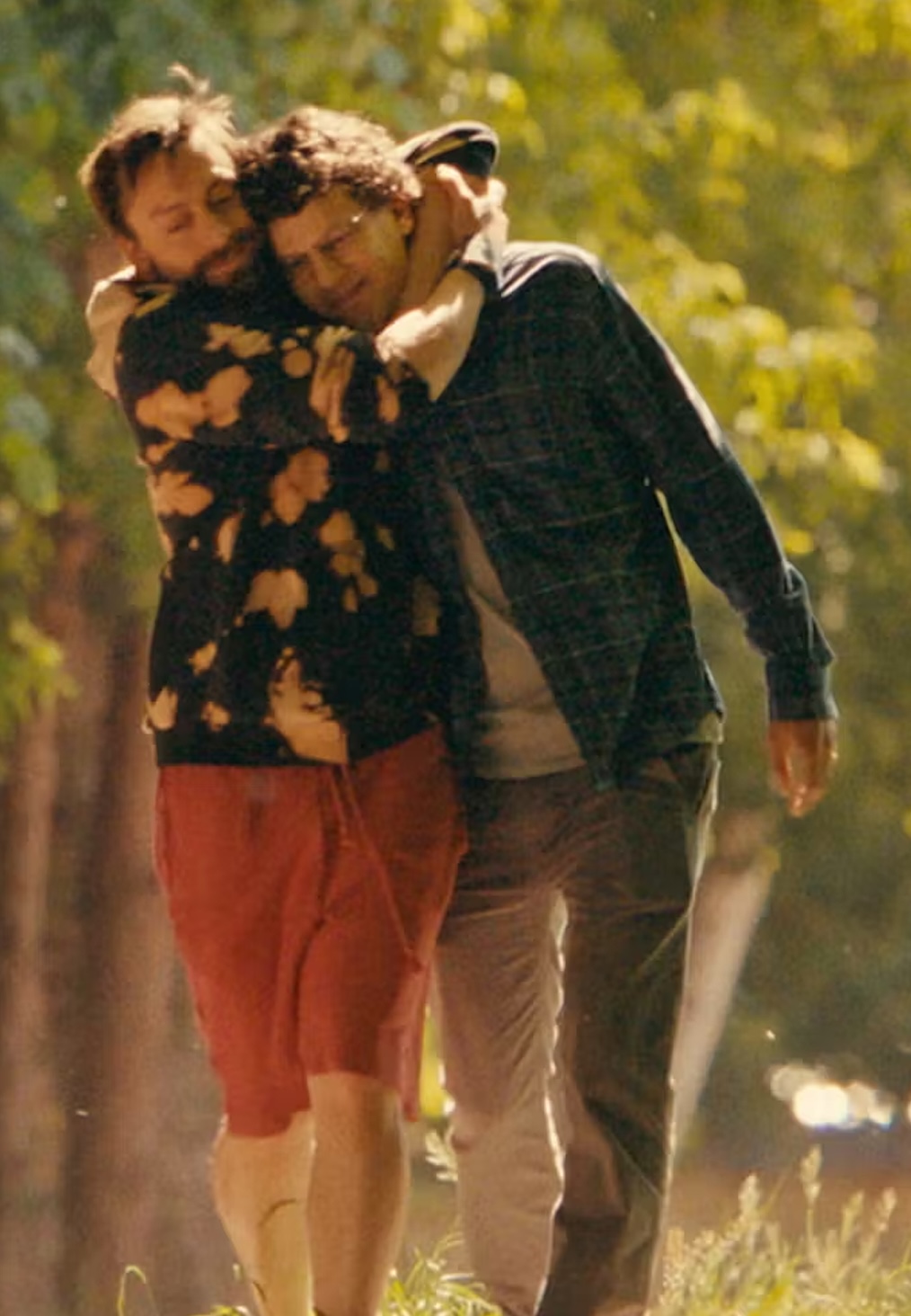

As the two of them progress on their journey, struggling at first but gradually adapting to a different kind of life, it becomes clear that there is something to be said for casting off the familiar shackles of a home and a mortgage. The couple find an inner strength they didn’t know existed and, along the way, they rediscover what drew them together in the first place. This could easily have been overly -sentimental but manages to pursue a less obvious route.

The story takes the duo across some jaw-dropping locations around Cornwall and Devon and the majesty of the scenery is nicely set against Chris Roe’s ethereal soundtrack. Anderson and Isaacs make a winning duo, conveying the real life couple’s indomitable spirit and genuine devotion to each other, while the various situations they stumble into range from the comical to the deeply affecting.

The film’s final drone sequence cleverly encapsulates its central message in one soaring extended shot. There have been some mean-spirited early reviews for The Salt Path but I find it genuinely moving and a cinematic journey worth sharing.

4.2 stars

Philip Caveney and Susan Singfield