27/04/24

Cameo Cinema, Edinburgh

National Theatre Live has chosen a propitious subject for its hundredth project.

Nye, written by Tim Price and directed by Rufus Norris, is the story of Aneurin ‘Nye’ Bevan, the Labour MP who conceived and delivered the National Health Service. I’m somewhat embarrassed to admit that beyond that one incredible achievement, I have no other knowledge of the man’s life, so this feels like the perfect time to find out more about him.

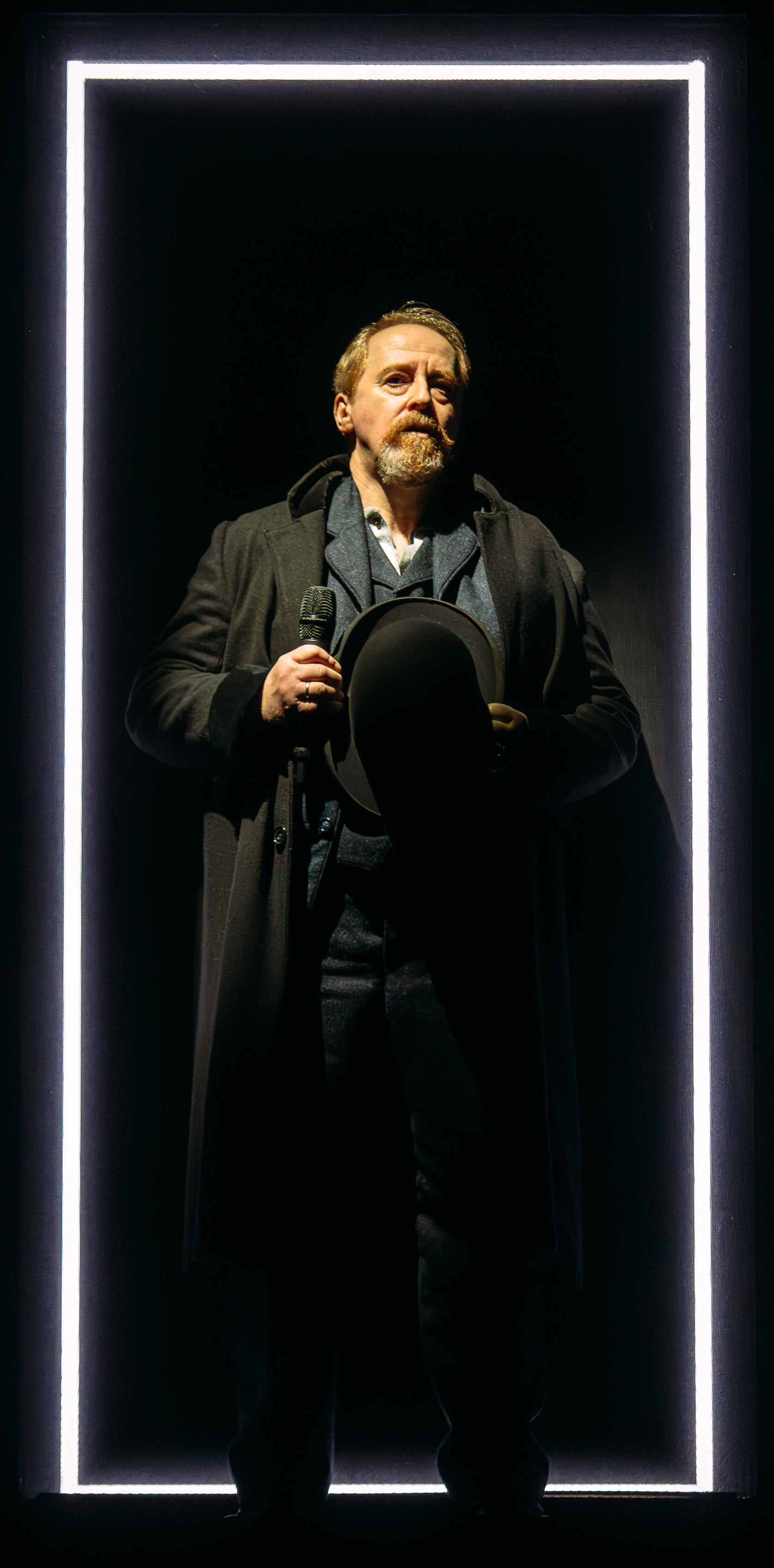

When we first encounter Nye (Michael Sheen), he’s a patient in one of the National Health hospitals he built. Accompanied by his ever-protective wife, Jennie (Sharon Small), and his best friend, Archie (Roger Evans), Nye has just undergone a routine operation for a stomach ulcer but it turns out there’s something much more serious causing the awful pains in his gut. Zonked out on drugs and hallucinating, his hospital bed takes on a magic carpet-like ability to whisk him back down the years to revisit key scenes in his life.

Vicki Mortimer’s ingenious set design is mostly achieved using curtains. They sweep from side to side, they descend from on high and sometimes they even rise magisterially from the floor, to alternatively create new spaces and reveal hidden depths within the Olivier’s expansive stage. Though Sheen remains dressed in his striped pyjamas throughout, there’s never any doubt as to where (and when) a particular memory is located.

We see Nye in childhood, afflicted by a stutter and brutalised by a sadistic teacher, but uniting his classmates in a show of defiance. We see him and Archie as older children, discovering the wonders of a library where… unbelievably…books can be borrowed and read – for free! And we see an older Nye, a fledgling politician now, arguing with his sister, Arianwen (Kezrena James), over the care of their father, David (Rhodri Meiler), a former miner succumbing to a slow and horrible death from black lung.

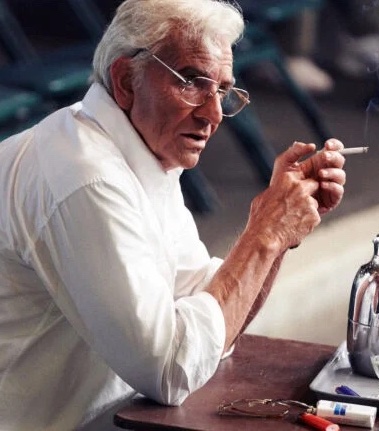

Later, Nye crosses swords with a bombastic Winston Churchill (Tony Jayawardena), who is violently opposed to handing out free health care to the oiks. Then, under a new Labour government, he accepts an offer from Clement Attlee (Stephanie Jacob, silently gliding around the stage behind a desk like a Doctor Who villain) to become Minister for Health – and Housing.

If certain elements of Nye’s life have been simplified for dramatic purposes (his huge collection of siblings is whittled down to a single sister, for instance), it matters little. The central premise of this story is so huge that it can’t be overburdened with detail.

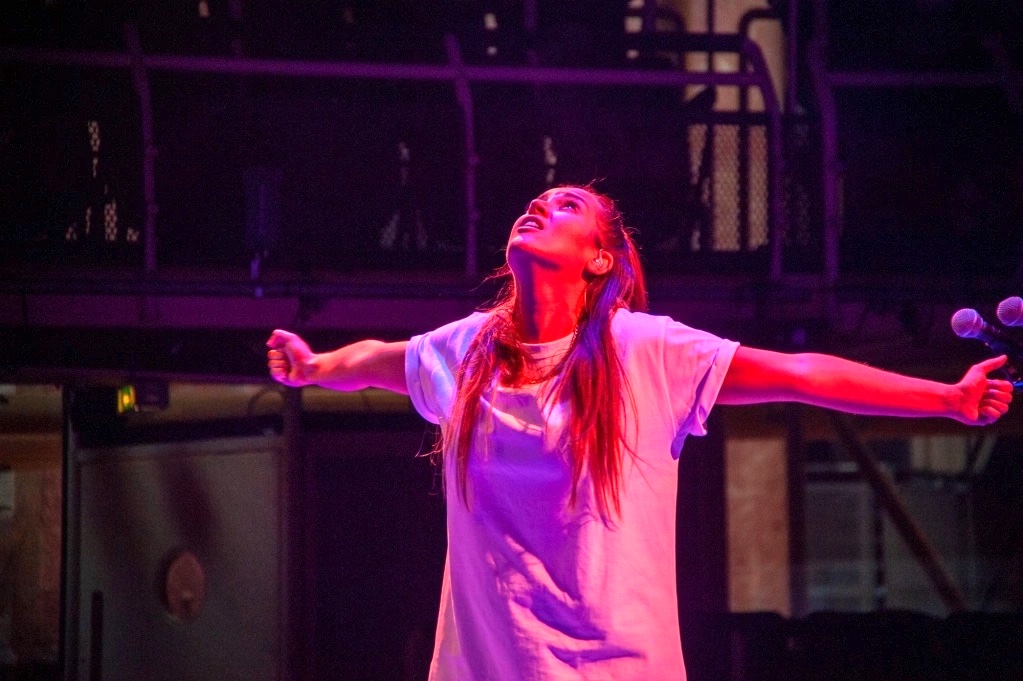

Sheen is terrific in the central role, giving Nye an understated and strangely vulnerable charm. Small is also marvellous as the firebrand, Jennie Lee – so good in fact that she should perhaps be given a little more to do, but that’s only a niggle. A sprightly rendition of Get Happy with Sheen singing and dancing his way around a busy hospital ward conveys Nye’s playful, engaging nature.

I love Jon Driscoll’s projection design, which utilises cinematic techniques. A key scene, depicting the death toll on the UK population after the end of the war, features hordes of monochromatic figures shambling helplessly towards the camera, only to morph into actual actors, appearing as if by magic, pleading for our help. Another sequence has Nye being scrutinised by the medical profession, scores of masked faces staring blankly at him across an abyss of prejudice. Who is this upstart who wants to change everything?

The play’s climax is almost unbearably poignant and I’m left sitting in the semi-darkness, tears in my eyes, marvelling at the sheer scale of one man’s glorious ambition. It seems particularly significant that. as I write this, a Tory government (which has spent so much time and effort trying to dismantle Aneurin Bevan’s wonderful achievement) looks set to be finally given its marching orders. Please let that happen!

Nye will doubtless be given other screenings soon, so keep an eye out for more opportunities if you missed it this time around. This is National Theatre Live at its most creative and enjoyable.

4.7 stars

Philip Caveney