12/12/25

Cineworld, Edinburgh

The festive season is upon us so what better time to release a charming, romantic comedy about, er… death? That’s Eternity’s central premise, but hey, don’t let it put you off.

In the film’s opening scenes, we join elderly couple, Larry (Barry Primus) and Joan (Betty Buckley), as they drive to a gender reveal party, bickering all the way there. What they haven’t revealed to their family members is that Joan is in the final stages of cancer and only has a short time left to live. But, ironically, it’s Larry who receives notice of an urgent appointment with his own mortality, thanks to getting a pesky pretzel stuck in his throat.

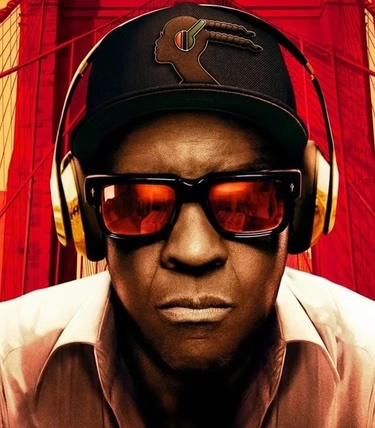

He suddenly finds himself on board a train as it arrives at ‘The Junction,’ a stopping-off place on the journey to Eternity. Larry (now played by Miles Teller) has been transformed to his younger self, able to do squats without pain, but understandably confused as to his current situation. Luckily, he’s been assigned an ‘Afterlife Co-ordinator’ called Anna (Da’Vine Joy Randolph) and, when Larry explains that his wife will be joining him any time now, Anna arranges special dispensation for him to wait for her.

In the meantime, Anna advises Larry to browse all the many brochures on offer in order to choose an Eternity that will be suitable for him and Joan. There are lots of different settings to choose from, ranging from different types of scenery to what can only be described as niche worlds. But Anna warns Larry that once a destination has been chosen, it cannot be changed – no matter what.

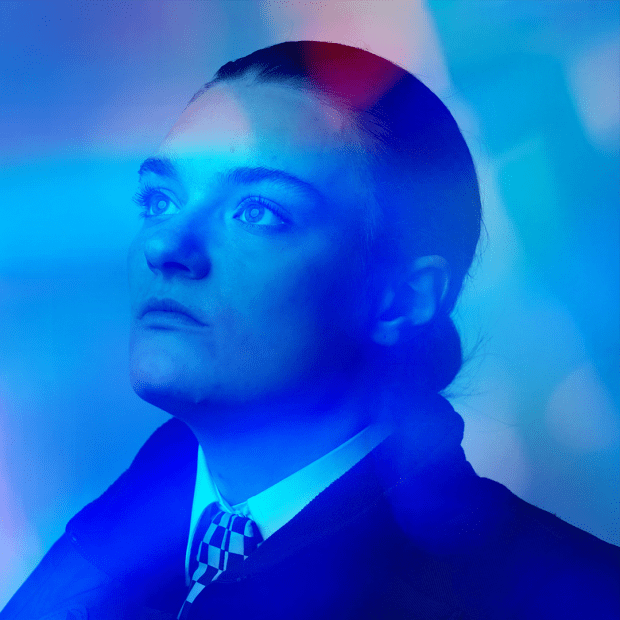

Soon enough, Joan arrives (looking uncannily like Elizabeth Olsen), and Larry is waiting eagerly to greet her. Unfortunately, so is Luke (Callum Turner), her first husband, who was killed in the Korean war. And he’s been waiting for more than sixty years to be reunited with her… which is awkward, to say the very least.

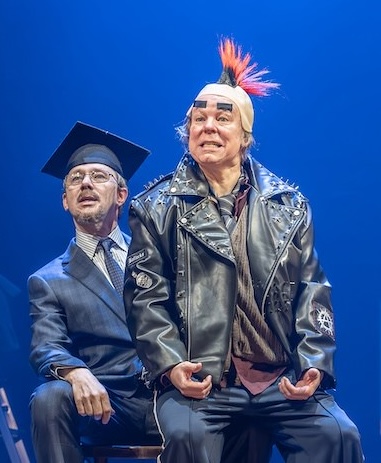

There’s lots to like about Eternity, not least its depiction of the afterlife, which has the general look and feel of a glossy holiday marketing exhibition, with representatives of the various destinations eager to sign up the recently deceased. I find myself laughing out loud at the absurdity of some of the concepts that prospective customers are offered. Germany in the 1930s but with 100% less Nazis? What’s not to like? And I love the ‘Archives’ where the dead can visit key scenes from their past, all of them presented as low-budget stage adaptations of the actual events.

The performances from the three leads are engaging and there’s some sparky interplay between Randolph’s Anna and Luke’s Afterlife Co-ordinator, Ryan (John Early). If I have slight reservations, it’s with the script, co-written by Patrick Cunnane and director David Freyne, which in its final stretches appears to bend some of the rules that it’s previously taken great pains to establish. But hey, it’s no deal- breaker. This is overall a thoughtful and engaging story with a pervading sense of melancholy.

If it occasionally invites comparisons with classics like Powell and Pressburger’s A Matter of Life and Death, well, that’s no bad thing either. Those seeking something a bit different this Christmas should find plenty here to keep them hooked. Just don’t take pretzels as your snack of choice.

4.2 stars

Philip Caveney