25/04/25

Cineworld, Edinburgh

I first saw this film in the cinema fifty-three years ago…

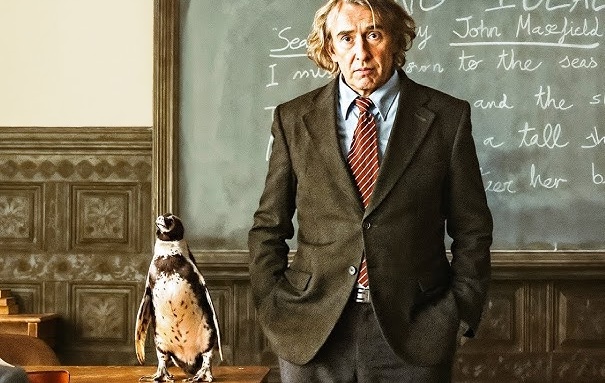

Wait. Stop. Can that be right? I mean, I understand that I’m getting old but… fifty-three years? But, yes, the dates do check out. And amazingly in 1972, when Pink Floyd at Pompeii was released, I had already been a fan of the band for half a decade. In 1967, in what was my final year at a rather horrendous boarding school in Peterborough, I was entranced enough by the Floyd’s second single, See Emily Play, to actually use some of my pocket money to buy a mono copy of their debut album, The Piper At the Gates of Dawn. Returning to school with it held proudly under my arm, I found myself surrounded by a gang of bigger boys, who sneeringly informed me that the Floyd were ‘degenerates who took drugs’ -unlike their favourite band, The Beatles. They then threw me to the ground and attempted to stamp all over my new purchase but luckily I was able to shield the album with my own body and it survived to be played another day.

I took great delight the following morning in strolling over to my assailant’s breakfast table and dropping a copy of a newspaper in front of them. The banner headline on page one was, “‘I took LSD,’ says Paul McCartney.”

The years rolled on. In 1969 I finally saw the band live at the Liverpool Philharmonic performing Umma Gumma, managing to procure a ticket for the equivalent of what might these days fall down the back of the average sofa. I emerged with the demeanour of somebody who had just witnessed the second coming of Christ. I remember that at one point the band wore gas masks and played in the midst of bright red smoke. I was by now a rabid fan.

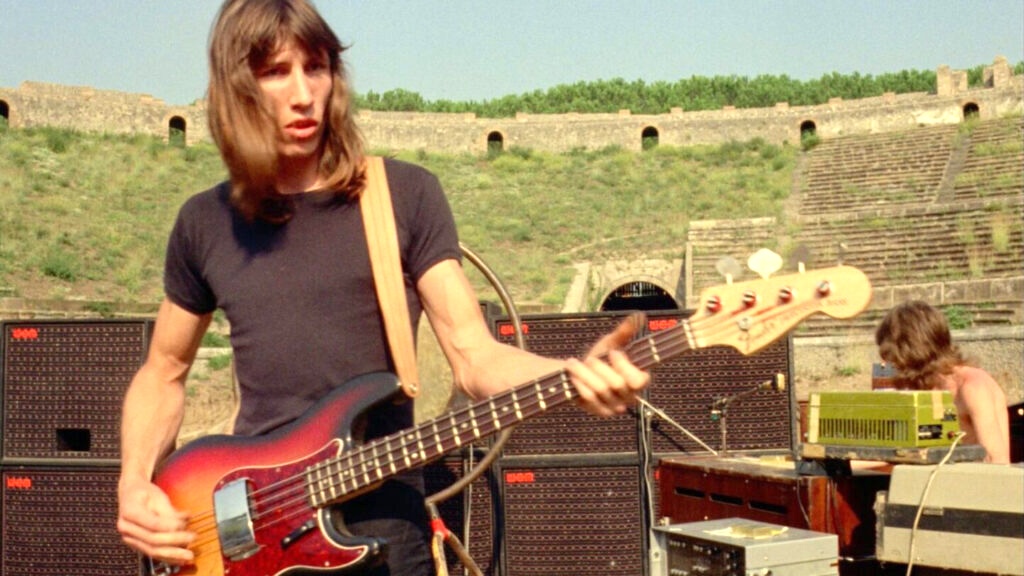

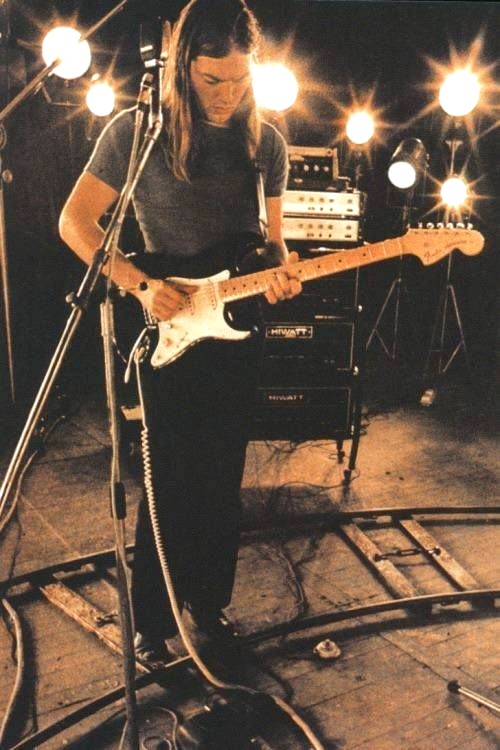

Which finally brings me to this re-release. In 1972, director Adrian Maben persuaded the band to go to the ancient ruins of Pompeii, set up their equipment in an empty arena and run through excerpts from their new album, Meddle, plus a selection of live favourites (Careful With that Axe, Eugene; A Saucerful of Secrets; Set the Controls for the Heart of the Sun). There’s no audience present unless you count the various film technicians and road crew, standing stripped to the waist in the baking sun and watching with apparent indifference as David Gilmour, Roger Waters, Richard Wright and Nick Mason unleash a barrage of sonic mayhem. On the directorial side there’s little in the way of special effects. Cameras, mounted on rails, prowl restlessly around the musicians as they play, sometimes tracking along behind stacks of sound equipment. At key moments in the Blitzkrieg, images of ancient statues, bubbling lava pits and fiery sunsets are inserted into the mix, Maben seeming instinctively to know when to augment a particular sound with a visual counterpoint.

What’s new here is the massive scale of an IMAX screen, a pin-sharp print and a crisp, clear digital sound mix that captures every last musical nuance in perfect detail. There are cutaways to the band ensconced at Abbey Road studios, working on what will be Dark Side of the Moon. The wonderful advantage of hindsight shows four young men who are quietly confident that their new brainchild will be good, but completely unaware that in just one year, they will be releasing one of the biggest-selling – and many would claim – greatest albums in history.

The next time I saw Floyd live, it was at Wembley Stadium, with that massive state-of-the-art show that included the infamous exploding aeroplane and levels of technical razzle-dazzle that changed the rock business forever. But it’s at Pompeii that I prefer to remember them, a youthful quartet just beginning to nuzzle hungrily at the edges of greatness, blissfully unaware of everything that’s about to follow. And I’m amazed to discover that Maben’s film is so ingrained in my memory that I can remember key shots and images as they unfold. It’s one hour and thirty-two minutes of sheer heaven for me and, glancing around the packed auditorium, I can see I’m not alone.

Stars? For me, this one can’t be anything less than the maximum allowed. After all, I’ve waited a very long time to see it. Again.

5 stars

Philip Caveney