26/05/25

Cineworld, Edinburgh

Cinema fans can hardly have failed to notice that a new Wes Anderson movie is on general release. As ever, it features his usual bag of tricks: impeccably-framed images arranged in perfect symmetry on the screen; an extended set of famous faces, all of whom show up for every successive project and seem happy to put in cameo performances for shirt buttons; and, as ever, a plot that appears to have been created simply to redefine the term ‘off-beat.’

Anderson has long been a disciple of Verfremdungseffekt – the distancing technique devised by playwright Bertolt Brecht, employed to prevent an audience from easy identification with his characters. It’s always been there in Anderson’s work to some degree but, this time around, I can’t help feeling that it might have been too enthusiastically applied.

Call me old-fashioned, but I do like a character I can root for. Here, there really isn’t one.

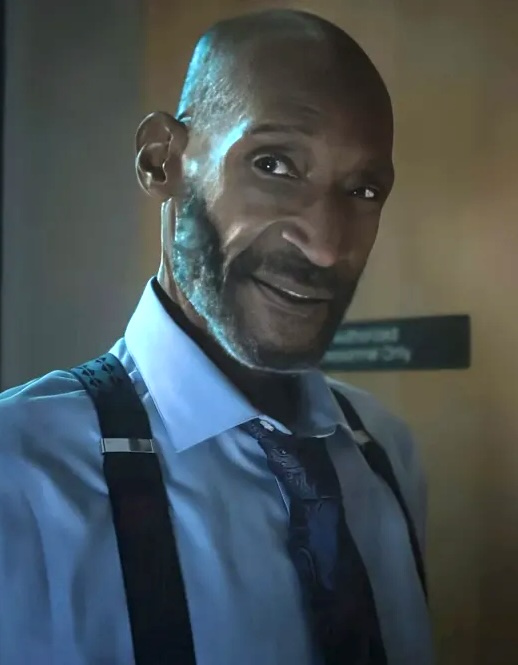

Wealthy and indomitable business magnate Zsa zsa Korda (Benicio del Toro) continues to thrive, despite the many assassination attempts that have been made on him by his rivals. After a near-fatal plane crash, he gets in touch with noviciate nun, Liesl (Mia Threapleton), who may just be his only daughter. (Korda has nine sons, several of them adopted, but he tends to spend as little time with them as possible.) Now, realising that he might be getting close to the end of his life, he has decided to offer Liesl a trial run as the sole heir to his considerable estate. He also takes on a new assistant, Bjørn Lund (Michael Cera), his last sidekick having been blown in half in the aforementioned plane crash.

The threesome must now travel around the fictional country of Phoenicia, where Korda has heavily invested in several major projects. A shadowy cabal of businessmen, led by Mr Excalibur (Rupert Friend), have raised the price of an all-important rivet used in the manufacturing process. This means that, unless Korda can persuade his business associates to take smaller profits, he is at risk of losing everything…

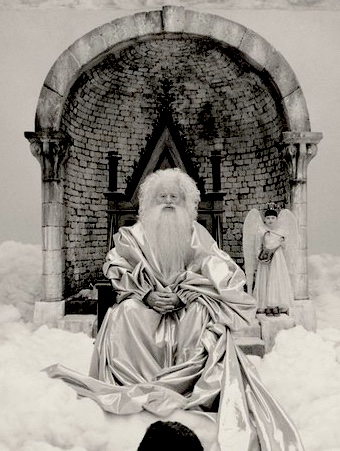

Even as I write this plot outline, I wonder why I’m bothering. Wes Anderson films are like art exhibitions. Some you love, though you cannot exactly pinpoint why. And others leave you flat for no easily-discernible reason. I’m not saying that The Phoenician Scheme is without merit. I sit watching it unfold, approving of its incomparable look and style, occasionally chuckling at some absurd lines of dialogue, even spotting the occasional movie reference. That Moroccan style club run by Marseille Bob (Mathieu Amalric), that’s a nod to Casablanca, right? And the black and white dream sequences, where Korda meets up with God (Bill Murray, naturally), are surely a reference to…

But this is pointless. I loved Anderson’s previous release, Asteroid City, which many viewers dismissed as another exercise in style over content. But this time, even I can’t seem to make myself care enough about the many characters I’m presented with. Korda’s growing relationship with Liesl could perhaps have been the hook that pulled me in, but that element feels somewhat under-developed.

That said, Anderson is one of the few film makers who walks his own path and refuses to compromise his vision. With names like Tom Hanks, Scarlett Johannsson and Benedict Cumberbatch ready and willing to bury their egos in walk-on roles, he’s in the rare position of being free to do exactly as he wishes.

So, why not give this a go? Chances are, you’ll completely disagree with me.

3.6 stars

Philip Caveney