15/03/24

Royal Lyceum Theatre, Edinburgh

I’m a massive fan of writer/director Emma Rice – and also of fairytales. I even wrote my own version of Blue Beard some years ago, a short story currently languishing in the proverbial drawer where unpublished fiction goes to die. So, co-produced by Wise Children, Birmingham Rep, HOME Manchester, York Theatre Royal, and – of course – Edinburgh’s Royal Lyceum, this adaptation promises to be a delight. It doesn’t disappoint.

We all know the story. Blue Beard is a charming villain: rich, handsome and very popular. Sure, he’s had more wives than Henry VIII, but he doesn’t pretend to be a saint, and it’s no surprise when a naïve young woman agrees to marry him. The surprise comes later, when he gives his new bride a key but prohibits her from using it, placing a temptation in her way that he knows she can’t resist. When, inevitably, she opens the forbidden door, she finds the dismembered corpses of his previous wives and understands immediately that she is next. Luckily, she has brothers, and they come riding to the rescue. And then – spoiler alert! – she lives happily ever after.

Naturally, things pan out a little differently here. Rice embraces the anarchic heart of the fairy tale, while simultaneously tearing it apart. The result is as chaotic and brash as anyone who knows her work will expect: maximalist and frantic and as unsubtle as the protagonist’s cerulean facial hair. I love it.

The music (by Stu Barker) is integral to the piece. It’s enthralling, and beautifully performed by the impressive cast, all of whom turn out to be quadruple-threats, not only dancing, singing and acting with aplomb, but also playing a range of instruments and, in the case of Mirabelle Gremaud, adding gymnastics and contortion to the mix.

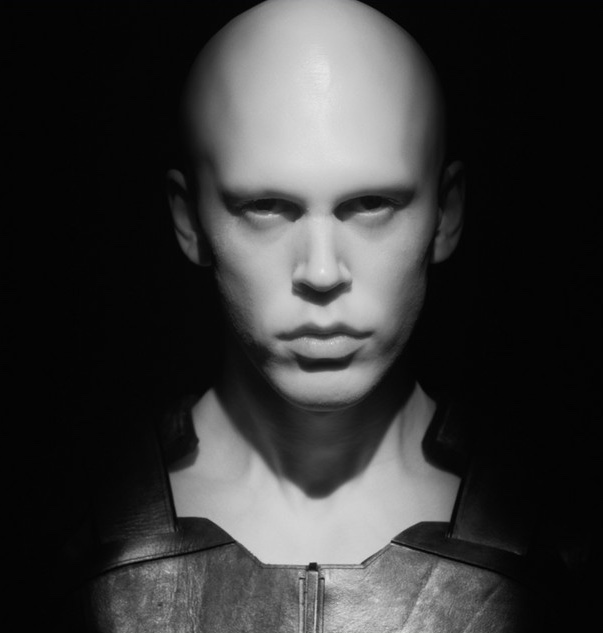

Vicki Mortimer’s ingenious set comprises boxes within boxes: indeed, the whole play is a magic show, all dazzling mirror-balls and sleights of hand. The cabaret glitz enhances the plot: no wonder Lucky (Robyn Sinclair) finds Blue Beard (Tristan Sturrock) spellbinding; he’s a magician, after all; illusions are his stock-in-trade. The thrilling, illicit pleasure draws us in: we too are seduced by Blue Beard’s ostentation and flair; excited as he conjures a horse race from nowhere; throws knives at his assistant (Gremaud); saws Lucky in half. This first act is all about the seductive allure of darkness, the impulse that makes us devour murder-mysteries and glamourise the bad guys.

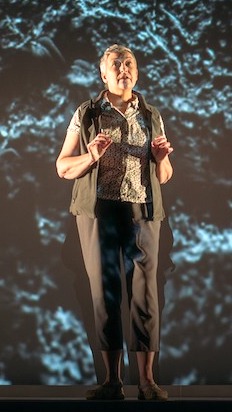

But Rice’s Blue Beard comes with a warning, in the form of Mother Superior (the fabulous Katy Owen), whose Convent of the Three Fs reminds us that real women – as opposed to their fairytale counterparts – are at once fearful, fucked and furious. She’s both narrator and chorus, veering between humour and rage, first undercutting the tension with a perfectly-placed “fuck off”, then skewering Blue Beard’s dangerous pomposity.

The second act draws all the disparate strands together. Lucky doesn’t have brothers who can rescue her, but she does have Treasure and Trouble, her mum and sister (Patrycja Kujawska and Stephanie Hockley), and Blue Beard is no match for this formidable trio.

Out in the real world, the Lost Sister (Gremaud) is not so lucky. A screen showing black and white CCTV footage of a man following a woman is a theatrical gut-punch, less visceral than the slo-mo, gore-spattered, cartoon battle we’ve just enjoyed, but much more chilling. The auditorium, which just a moment ago was a riot of whoops and claps, is silent, aghast. The Lost Brother (Adam Mirsky) weeps; the Mother Superior sheds her habit. The smoke clears; the illusion breaks.

This is theatre with a capital T.

5 stars

Susan Singfield