24/08/23

Traverse Theatre, Edinburgh

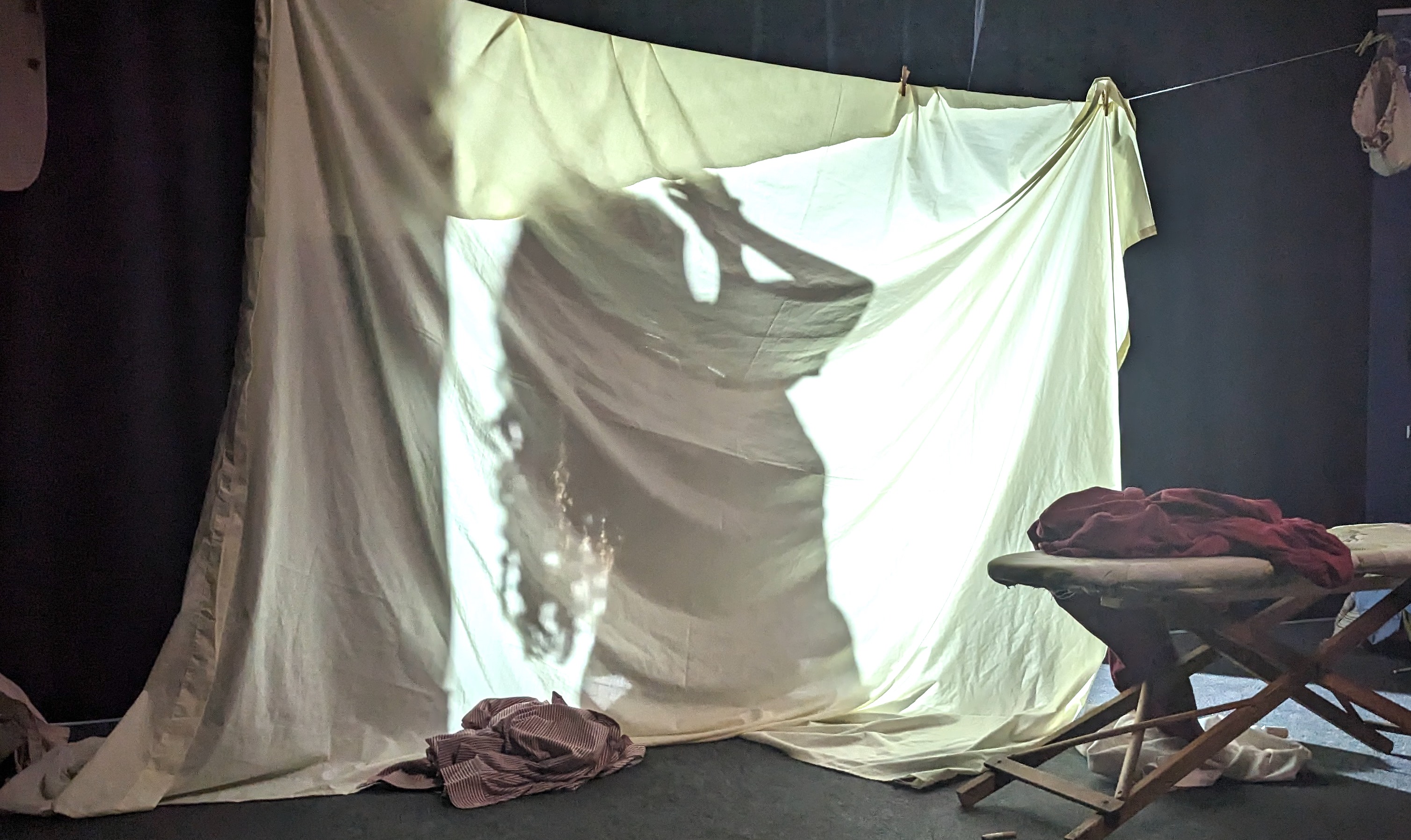

Nassim (the play) is six years old, and has been performed by hundreds of acclaimed actors, including Whoopi Goldberg, David Greig and Cush Jumbo. The conceit is simple: each actor only performs the show once – without any rehearsal and having never seen the script. Nassim (Soleimanpour – the playwright) directs via a backstage camera and a loose-leaf script. Soleimanpour is Iranian but his plays have never been performed in Iran; Nassim is about his attempts to express himself creatively without being able to use his mother tongue. One by one, the actors speak for him, acting as a conduit for Soleimanpour’s words. It’s powerful and affecting.

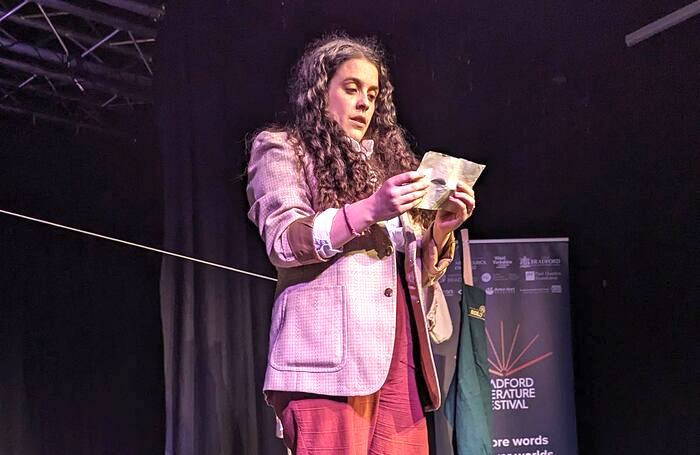

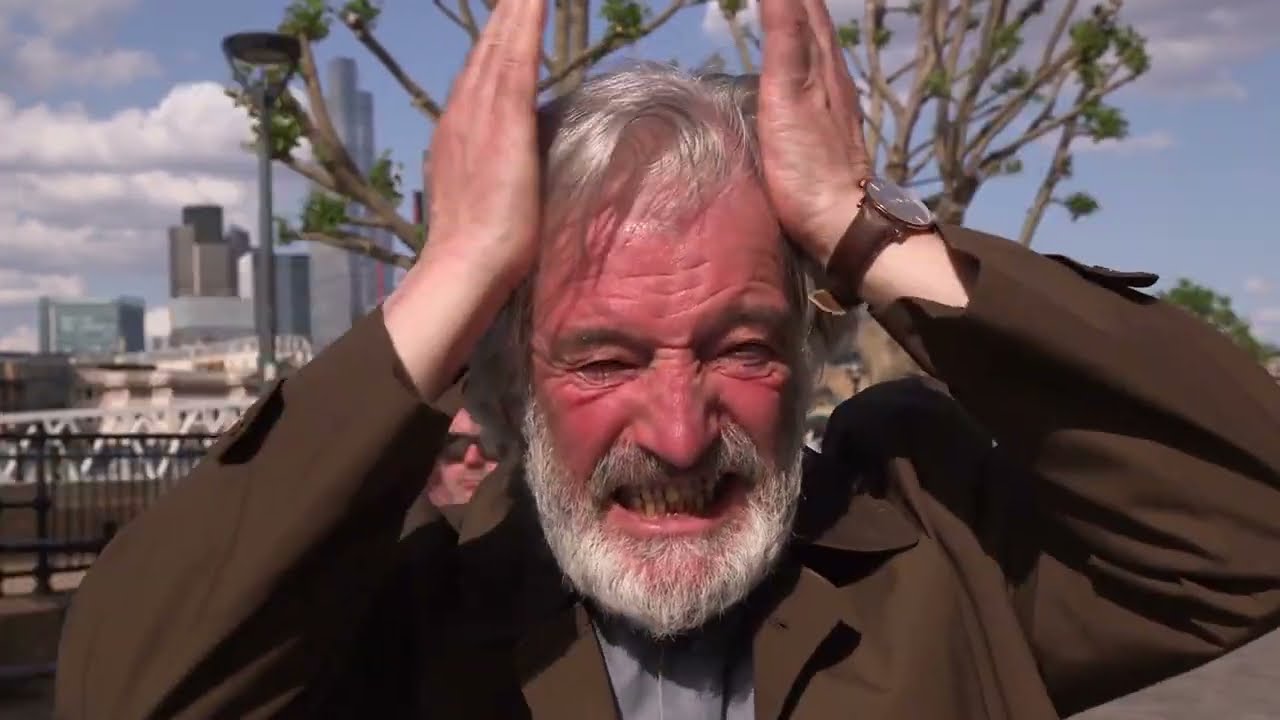

Tonight’s actor is Greg McHugh, best known to us as the terrifying Teddy in BBC Scotland’s Guilt. I’m happy to report that he seems a lot cuddlier in person, approaching Soleimanpour’s script with warmth, respect and humour. He gamely follows all of the instructions, including the more out-there ones, such as holding a sugar lump in his teeth (it makes sense soon after) and accepting cherry tomatoes as punishment for errors in a language game.

But Nassim isn’t just a play: it’s a lesson in Farsi and a reaching out across divides. The tone is gentle and benevolent, provoking smiles rather than laughs – and then, finally, tears. It’s a way for Soleimanpour, a conscientious objector, to reclaim his voice, to subvert the Iranian government’s attempts to silence him. For years, he was unable to leave Iran, and so he sent his scripts out into the world without him; now, he lives in Germany, and travels with them, joining the paper-doll chain of performers onstage, forging those connections in person. He’s freer than he used to be, but it comes at a price. He’s left behind his home, his family. His mother. Mumun. He teaches us a phrase: Delam tang shod barat. I miss you.

Only the hardest of hearts could fail to melt.

4.5 stars

Susan Singfield