03/10/25

The Studio at Festival Theatre, Edinburgh

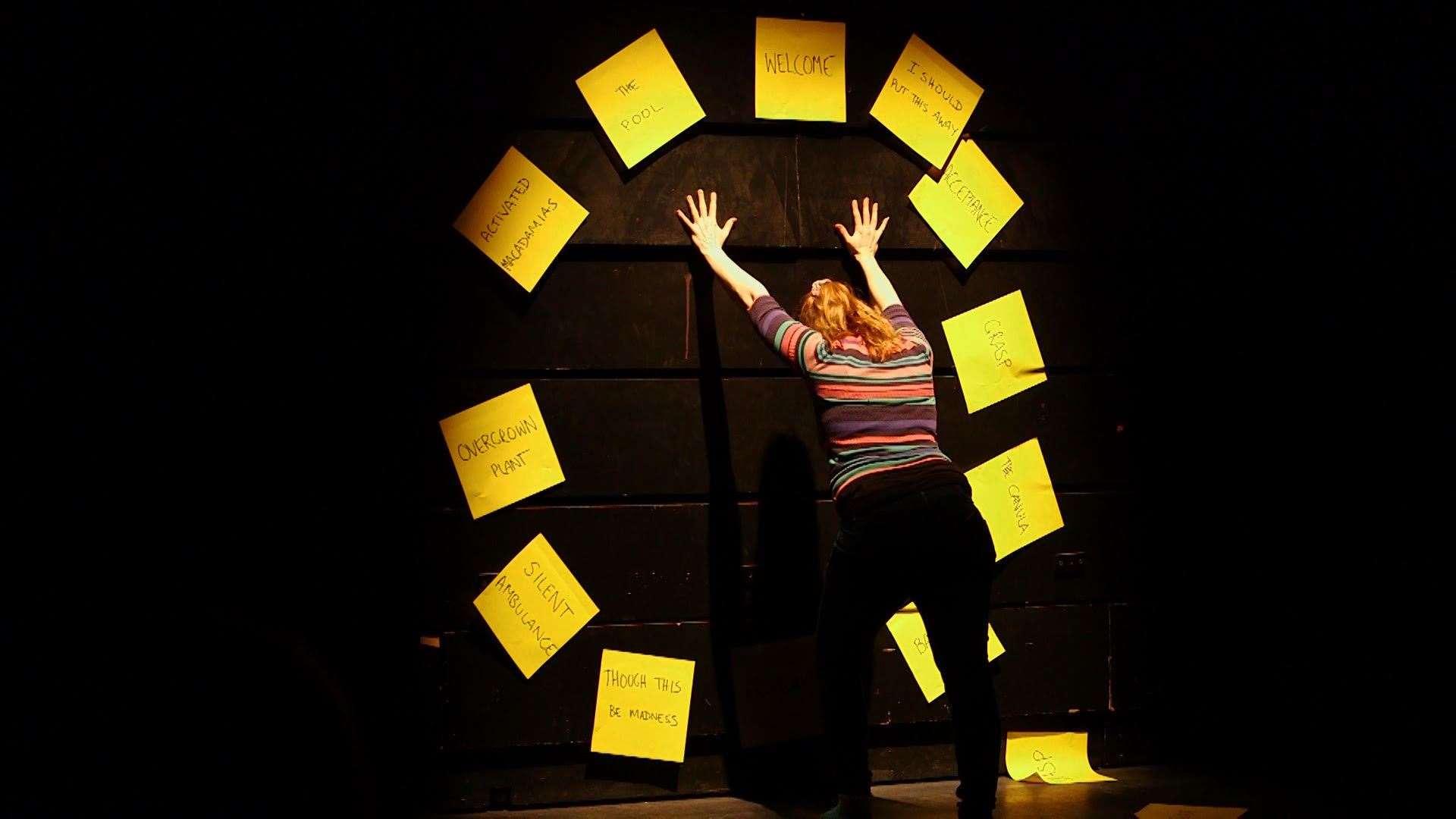

Writer-director Fraser Scott explores the knotty relationship between language and identity in this searing polemic, which – despite the complexity of the subject – is both accessible and very funny.

Bonnie (Olivia Caw) is fae Paisley, where she lives with her beloved Papa and speaks like him too. She’s sparky and clever and, as she grows up, keen to spread her wings and see the world.

Step one is St Andrew’s University, where her flatmates are all from England or Edinburgh – “aun a dinnae ken which is worse.” They tease Bonnie about the way she speaks, and she gives as good as she gets, mocking their accents in turn. But of course it’s not the same. The English girl who says, “You have to be okay with how we sound too,” is missing the point. The way she sounds isn’t always on the brink of being wiped out, has never been banned, will never disadvantage her. But Bonnie doesn’t yet have the words to articulate this point.

Step two is a year in the USA, where even those who enthusiastically claim their “Scotch” ancestry struggle to understand anything Bonnie says. She finds herself having to speak slowly and Anglicise her language, which seems harmless enough but it’s tiring. It takes its toll.

Back on home turf, a graduate now, killing time while she works out what she wants to do with her life, Bonnie is disconcerted by Papa telling her that she sounds different: “pure posh.” She realises she has to make a choice. Will she sacrifice her voice to achieve success in an unequal world, or will she roar at the injustice and fight to be heard on her own terms?

This is a demanding monologue and Caw’s performance is flawless, at once profound and bitingly funny: the jokes delivered with all the timing and precision of a top comedian; the emotional journey intense and heartfelt.

Patricia Panther’s sound design is integral to the production, and I especially like the use of multiple microphones, clustered to denote new places and people. Admittedly, there’s a lot of competition from Storm Amy raging outside and rattling the pipes, but it’s effective nonetheless.

Fraser makes his points cogently, probing both the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis (that the language we use shapes the way we think) and the repercussions of linguistic colonialism. As a Welsh woman, I’m familiar with historical tales of school-kids being punished for speaking Cymraeg, but the Scots issue is clearly ongoing. In fact, as I leave the theatre tonight, I bump into one of the teenagers who attends the drama club I teach. He tells me that he was sent out of class recently for saying, “I ken,” that his teacher deemed his language “cheeky.” I think his teacher needs to see this play.

Kinetic and engaging, Common Tongue has a lot to say and a braw way of saying it.

5 stars

Susan Singfield