21/07/22

NT Live, The Cameo, Edinburgh

It is a truth universally acknowledged that Jodie Comer is a formidable talent, and I am more than happy to add my voice to the fangirl choir. Not only is she a chameleon, she’s also bristling with charisma, and she’s perfectly cast to play this complex, demanding role. The only difficulty is in believing this is her stage debut – because she seems born to it. She is a theatrical tour de force.

Prima Facie is, essentially, a feminist polemic, and a much-needed one. Art, as Aristotle sort of said, is multi-purpose, and can be used to educate as well as simply entertain. And boy, do we need educating. In the UK, a shocking 99% of reported rapes don’t even make it to court, and – of those that do – fewer than a third lead to a guilty verdict. When we take into consideration the enormous number of sexual assaults that are never reported at all (an estimated 83%), there’s only one conclusion to draw: the system isn’t working. Rape is a horrendous crime, but it’s one you’re likely to get away with.

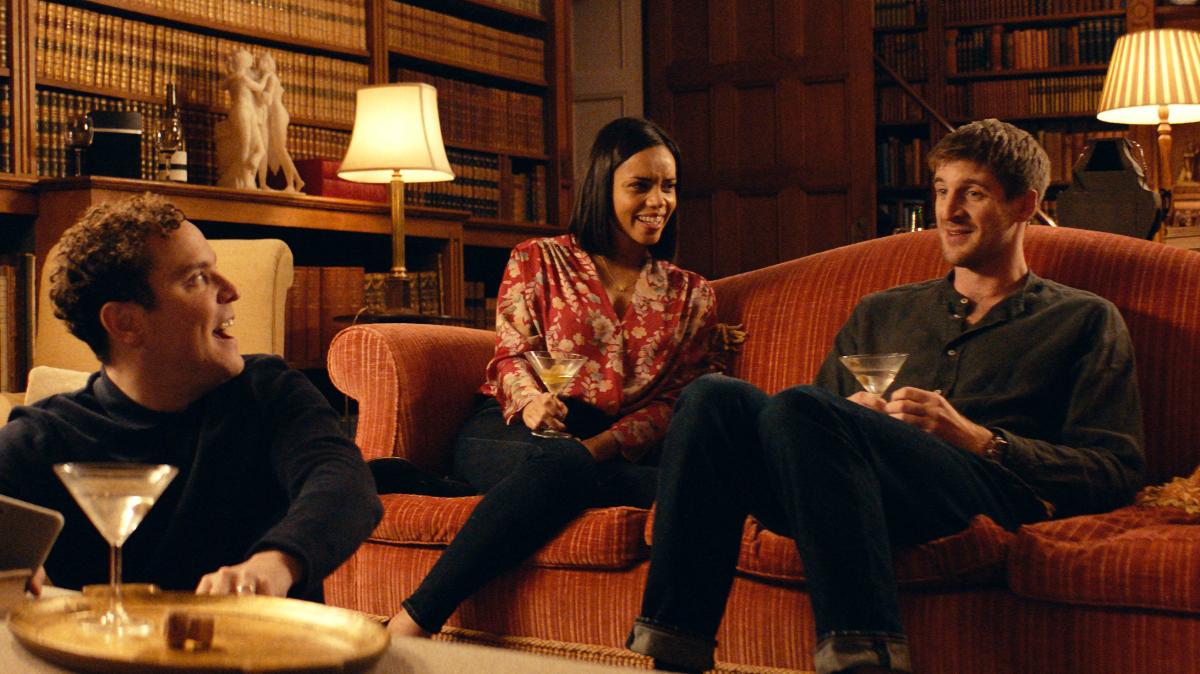

Australian playwright Suzie Miller is on a mission to address this. She used to be a criminal defence lawyer, specialising in human rights, and she realised then that something was amiss. The law, she says, is built on assumptions that don’t acknowledge the realities of rape, without any real understanding of what consent looks like in practice, nor of how a victim might present. And so Prima Facie, directed by Justin Martin, comes howling into the void, forcing us to consider the urgency of change. The sold-out run at London’s Harold Pinter theatre, and the packed live-streamings at cinemas across the land, suggest there’s a lot of support for the idea (as well as a lot of Killing Eve fans, of course).

Comer plays Tessa, a brilliant young woman, who’s made it against the odds. Her first battle – as a state-educated Scouser – was getting into Cambridge law school; her second was graduating; her third becoming a barrister. She’s on the up, winning, sniggering at a young wannabe who asks of a rapist, ‘But is he guilty?” – because objective truth isn’t what she seeks. It’s “legal truth” that matters, which lawyer is best at playing the game. And she’s a fine player, one of the best. Lots of accusees are walking free because of her.

Until, one day, Tessa is raped. It’s a messy, complicated case, the type she knows she’ll never win. She was drunk; she’d had sex with the perpetrator before; she hasn’t any evidence. The whole legal edifice – the thing she’s dedicated her life to – comes crumbling down; the scales fall from her eyes. Her rapist will get off scot-free, thanks to someone like her, just doing their job. And the change in her is utterly and devastatingly believable. She’s always been determined. This might be a losing battle, but she’ll go down fighting.

The staging (by Miriam Buether) is an interesting blend: the piece opens in the naturalistic confines of a stuffy, traditional chambers, but the tables are soon being utilised as a courtroom, the chair as a toilet; costume changes happen slickly, on stage: Comer is her own dresser, as well as her own stage hand. Out on the street, after the assault, rain falls almost literally on her parade, washing away her former swagger. The lights change, the stage becomes a suffocating black box, and a projected calendar reveals the shocking truth of just how many days it takes to get your case to court. Years are lost.

The score, composed by the ever-fabulous Self-Esteem (Rebecca Lucy Taylor) perfectly complements the piece – it’s an intelligent marriage of art forms.

I won’t reveal whether Tessa wins; you can consider the statistics and place your bets. What she does do is deliver a final speech that, while it isn’t necessarily believable, is a perfect piece of wish-fulfilment. It’s all the conversations she’s had in her head during the three years she’s been waiting; it’s her fantasy moment, raising her voice and finally being heard.

This is a call to action that walks the walk, directly supporting The Schools Consent Project, “educating and empowering young people to understand and engage with the issues surrounding consent and sexual assault”. It’s also a powerful, tear-inducing play.

More, please.

5 stars

Susan Singfield