17/06/25

The Cameo, Edinburgh

Lollipop is writer-director Daisy-May Hudson’s debut feature film – and what a promising start this is. Sure, she’s treading in the footsteps of working-class champions such as Ken Loach and Mike Leigh, but – if this fiercely female and decidedly 2020s tale is anything to go by – Hudson is also forging her own path.

‘Lollipop’ is Molly (Posy Sterling)’s childhood nickname, but she’s come a long way since those innocent days. She’s just spent four months in prison – for an unspecified crime – and is looking forward to getting out and being reunited with her kids, Ava (Tegan-Mia Stanley Rhoads) and Leo (Luke Howitt). But things have gone awry while she’s been away: not only has she had to give up her flat, but her flaky mum, Sylvie (TerriAnn Cousins), who was supposed to be looking after the children, has handed them over to social services instead. “Don’t start,” she says, when Molly confronts her, aghast. “I can’t cope with you starting.”

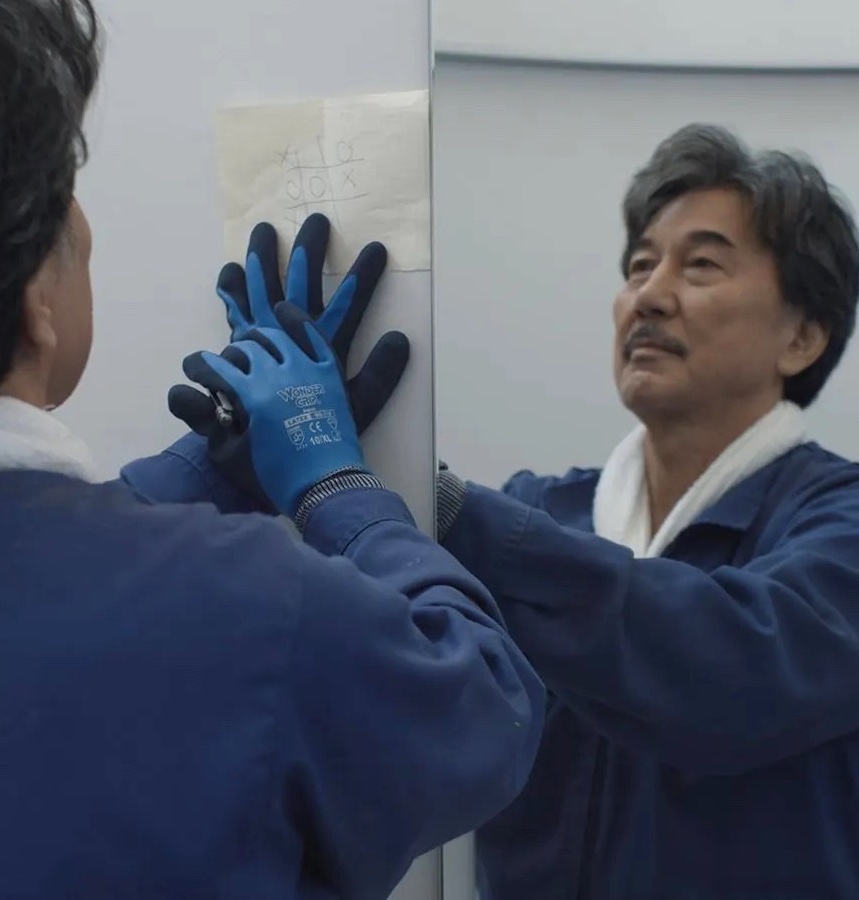

Of course, once they’re in the system, the children can’t just be handed back. There are teams of people tasked with ensuring their welfare. How can they return Ava and Leo to Molly’s care when she’s homeless, pitching her tent illicitly in the park, washing in a public loo? But it’s Catch 22: Molly isn’t a priority for housing because she hasn’t got her kids with her. She’s going round in circles, and that’s not helping her already fragile mental health. However caring the individual professionals are – and they are decent, compassionate women, on the whole – the process seems designed to deny her any possibility of making good.

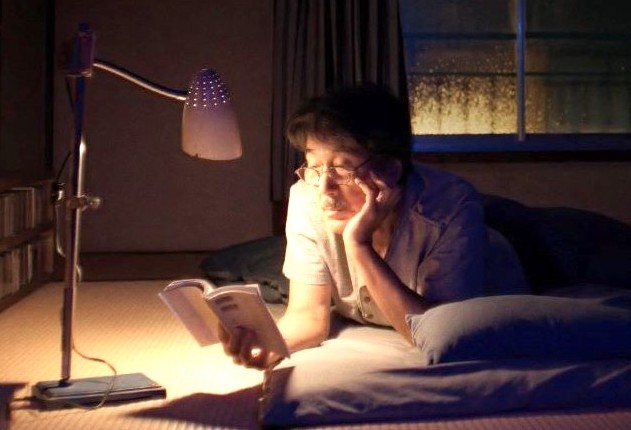

A chance encounter with an old school friend, Amina (Idil Ahmed), offers a glimmer of hope. Amina has her own problems: she’s separated from her husband, and living in a hostel with her daughter, Mya (Aliyah Abdi). But Amina is a natural optimist with an abundance of energy, spreading joy in the simplest of ways. She hosts a daily ‘party’, where she and Mya dance to their favourite tunes, while a disco ball transforms their dismal walls with colour and light. When Molly reaches breaking point, afraid she’s going to lose her kids forever, it’s Amina who breaks her fall…

It’s impossible not to draw comparisons with the second series of Jimmy McGovern’s acclaimed TV series, Time, which saw Jodie Whittaker’s Orla facing a similar situation, fighting against a failing and underfunded system that not only hurts people but also encourages recidivism. This doesn’t detract from Lollipop‘s power; sadly, it only serves to highlight the ordinariness of this extraordinary horror.

Sterling imbues the central role with so much heart that I defy anyone not to cry when they see Molly lose the plot at a resource centre, not to hold their breath while they wait for the court’s verdict. Newcomer Ahmed is also perfectly cast, lighting up the screen with her ebullience, although Amina also experiences great pain. Cousins infuriates as the selfish Sylvie, letting Molly down at every turn, but somehow still evoking our pity, and young Rhoads is heartbreakingly convincing as a little girl negotiating adult trauma before she’s even hit puberty.

Lollipop is a devastating but beautifully-realised film, as vital and engaging as Sean Baker’s The Florida Project (with which it shares some DNA). It’s the sort of potent story that ought to be the catalyst for change. Let’s hope.

4.5 stars

Susan Singfield