24/08/23

Underbelly Cowgate (Belly Button), Edinburgh

One Way Out by Theatre Peckham’s NO TABLE productions is a deserving winner of Underbelly’s Untapped award, “a game-changing investment in early and mid-career theatre companies wanting to bring their work to the world’s biggest arts festival”. Hats off to Underbelly: if we want the Fringe to be an inclusive event, one that celebrates vibrancy and creativity, then financial support like this is a must. And One Way Out is certainly worth backing.

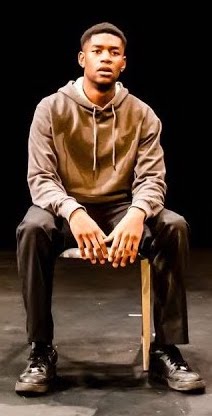

Written and directed by Montel Douglas, this is the tale of four friends, poised on the brink of adulthood, awaiting their A level results and planning their futures. The performances are high-octane; the direction bold and energetic. The boys are nervous about leaving school, but excited too. Tunde (Marcus Omoro) is focused on getting to university, the first step towards his dream of “a job with a suit”. Salim (Adam Seridji) plans on expanding his family’s business; his Uncle has one shop, but Salim will have many. Meanwhile, Paul (Sam Pote) is struggling academically. He does like performing magic tricks though. Maybe he could do something with that? Of the four, Devonte (Shem Hamilton) is the least certain of what he wants. He’s too busy worrying about his mum, who is on dialysis. Tunde is concerned about him. “You’re clever,” he tells his friend. “You’ve got to think about yourself as well as your mum. You should at least apply to university.”

But Jamaican-born Devonte’s UCAS application is his undoing. He doesn’t have the relevant documentation, can’t prove his leave to remain in the UK. He’s been here since he was nine years old, but now he’s being sent away…

Inspired by Douglas’s own memories of a cousin who was given a deportation notice at nineteen, One Way Out is a deceptively clever piece. Beneath all the fun and banter, all four young men are preoccupied with the question of what will happen to them, what their futures will look like. They’re dizzy with possibility. Devonte’s misfortune sends shockwaves through the group – and through the audience. It seems impossible that he should be uprooted against his will, torn from everything he knows – his friends, his sick mother – punished, as if he is a criminal. It should be impossible. Tragically, it is not. The Windrush scandal shames Britain, and Devonte’s plight highlights the atrocity. “It’s seventy-five years since the Windrush arrived,” Devonte says. “And seventy-five years since the NHS was founded. That’s not a coincidence.”

I like that the piece is brave enough not to offer a solution. There isn’t one. Three of the boys move on, for better or worse, into their adult lives, but we don’t find out what happens to Devonte because he’s gone. His friends’ efforts to save him fail. The system is brutal and its consequences dire. The audience just has to hope that Devonte will find happiness, and that Jamaica treats him better than the UK ever did.

4.3 stars

Susan Singfield