30/05/24

Lyceum Theatre, Edinburgh

Lewis Grassic Gibbon’s Sunset Song is widely regarded as one of the most important Scottish novels of the 20th century. There are many who first encountered it as a set text in school and have carried it in their hearts ever since. Playwright Morna Young was evidently one such teenager and this is her adaptation of the tale in collaboration with Dundee Rep. I’ll confess that I’ve never got around to reading the book myself. Set in the 1900s, it’s a dour and sometimes bleak story based around the misadventures of the Guthrie family, farmers who live and work in (the fictional) Kinraddie in the wilds of Aberdeenshire.

When we first meet Chris Guthrie (Danielle Jam), she’s young and ambitious, a keen reader and already planning to seek a career as a teacher. In this, she has the grudging support of her father, John (Ali Craig), though he’s a hard taskmaster, never slow to hand out physical punishment to Chris and her siblings whenever they step over what he perceives as ‘the line.’

Chris’s much-loved mother, Jean (Rori Hawthorn), mentally broken by the recent birth of twins, takes matters into her own hands, killing herself and her new babies. Two younger children decide to flee the family home to start a new life in Aberdeen and it isn’t long before Chris’s older brother, Will (Naomi Stirrat) follows their example and heads off to seek his own fortune in Argentina. This leaves Chris to run the farm with her father and, after he suffers a debilitating stroke, to fend off his sexual advances. When tragedy strikes yet again, Chris finally has an opportunity to start over but (maddeningly) she decides to stay where she is and marry local boy Ewan (Murray Fraser). But by now, the world is heading into a massive global conflict and it’s hardly a spoiler to say that more heartbreak is looming on the horizon…

While it does of course feature more than its fair share of harrowing occurrences, it’s to this production’s credit that it manages to convey difficult themes without ever feeling too prurient. Young’s adaptation remains true to the novel’s Doric dialogue, though occasionally I feel I’m told things that I would rather see – and the decision to have no costume changes when actors embody several different characters does mean that I’m occasionally confused as to who is who.

Emma Bailey’s simple but effective set design is based around a large rectangular section of soil, across which the characters walk barefoot, fight, make love and celebrate. The story’s central theme couldn’t be more evident. To the Guthries, the earth is all-important. It provides sustenance, a wage and a reason to go on living. And of course, it is also the place to which they will eventually return. As if to accentuate this, the backdrop is a closeup of a field of wheat.

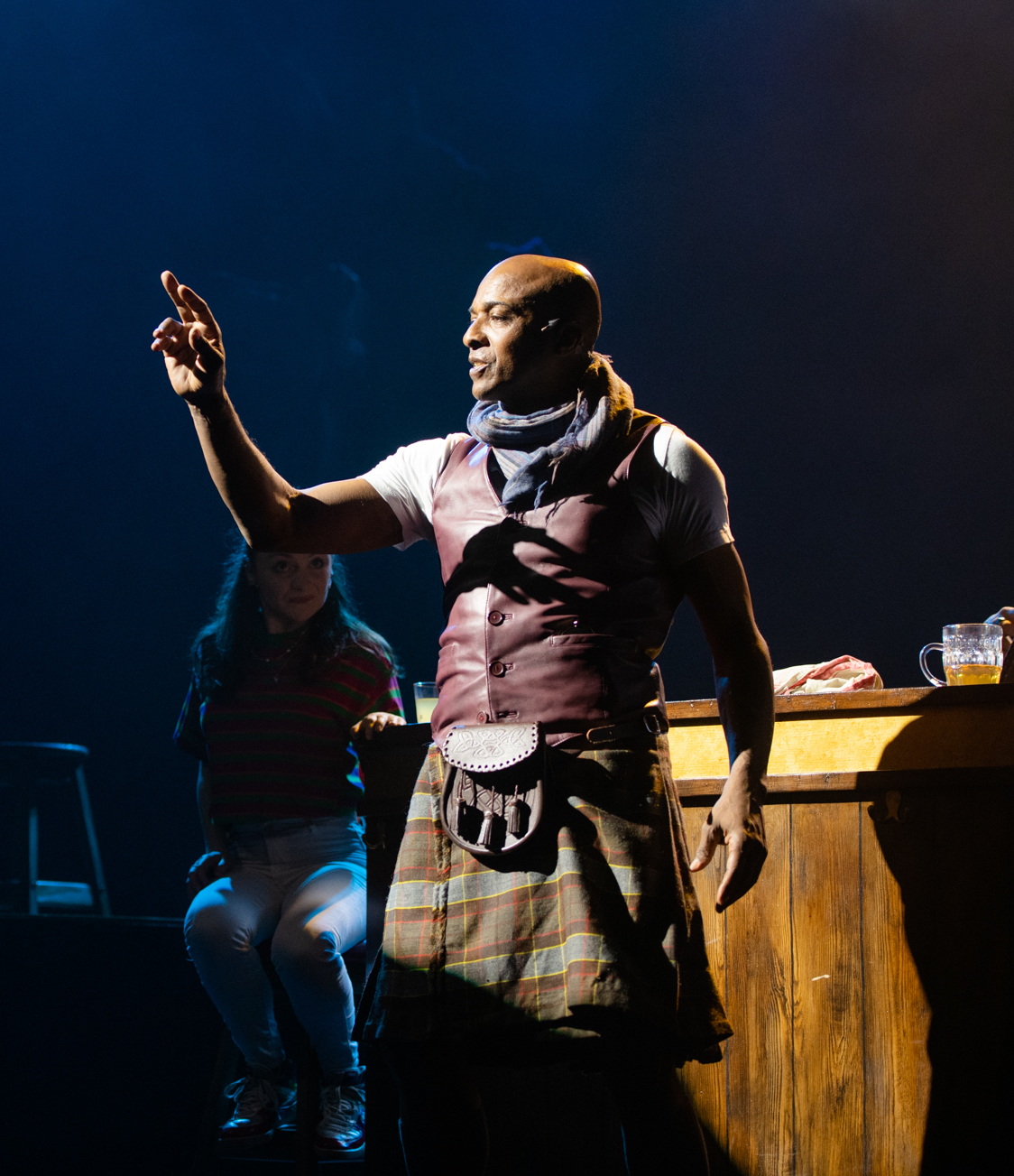

On either side of the soil, musical instruments are arranged and the cast occasionally break off to deliver Finn Anderson’s evocative songs, singing in plaintive harmonies, pounding propulsive drums, strumming electric guitars and at one point even launching headlong into a spirited wedding ceilidh. These elements offer a welcome respite from the unrelenting bleakness of the story.

Finn de Hertog’s direction is assured and I particularly enjoy Emma Jones’ lighting design, which manages to convey that simple slab of soil in so many different ways. I like too that many of the props the actors require are clawed up out of the ground like a strange crop.

But much as I’d like to, I can’t really warm to the story, which at times feels uncomfortably like a series of disasters unleashed upon one luckless family.

3.6 stars

Philip Caveney