15/08/25

Cineworld, Edinburgh

Yes, I know it’s the Fringe and I do appreciate that cinema is supposed to be taking a back seat this month, but anyone who caught Zach Creggar’s debut movie, Barbarian, back in 2022, will doubtless be as fired up for his sophomore feature as I am. Like its predecessor, Weapons is a wild ride, one that has more twists and turns than a passenger could ever anticipate. I sit spellbound as I am thrown this way and that, sometimes mystified, occasionally terrified, but never ever bored.

The story begins with an inexplicable event. In the little town of Maybrook, Pennsylvania, teacher Justine Gandy (Julia Garner) arrives at school, ready to teach her class – to find only one pupil waiting for her. He’s Alex (Cary Christopher) and he’s the only kid left because, earlier that same morning (at 2.17am precisely), all his classmates woke up, got out of their beds and ran off into the night with their arms held out at their sides.

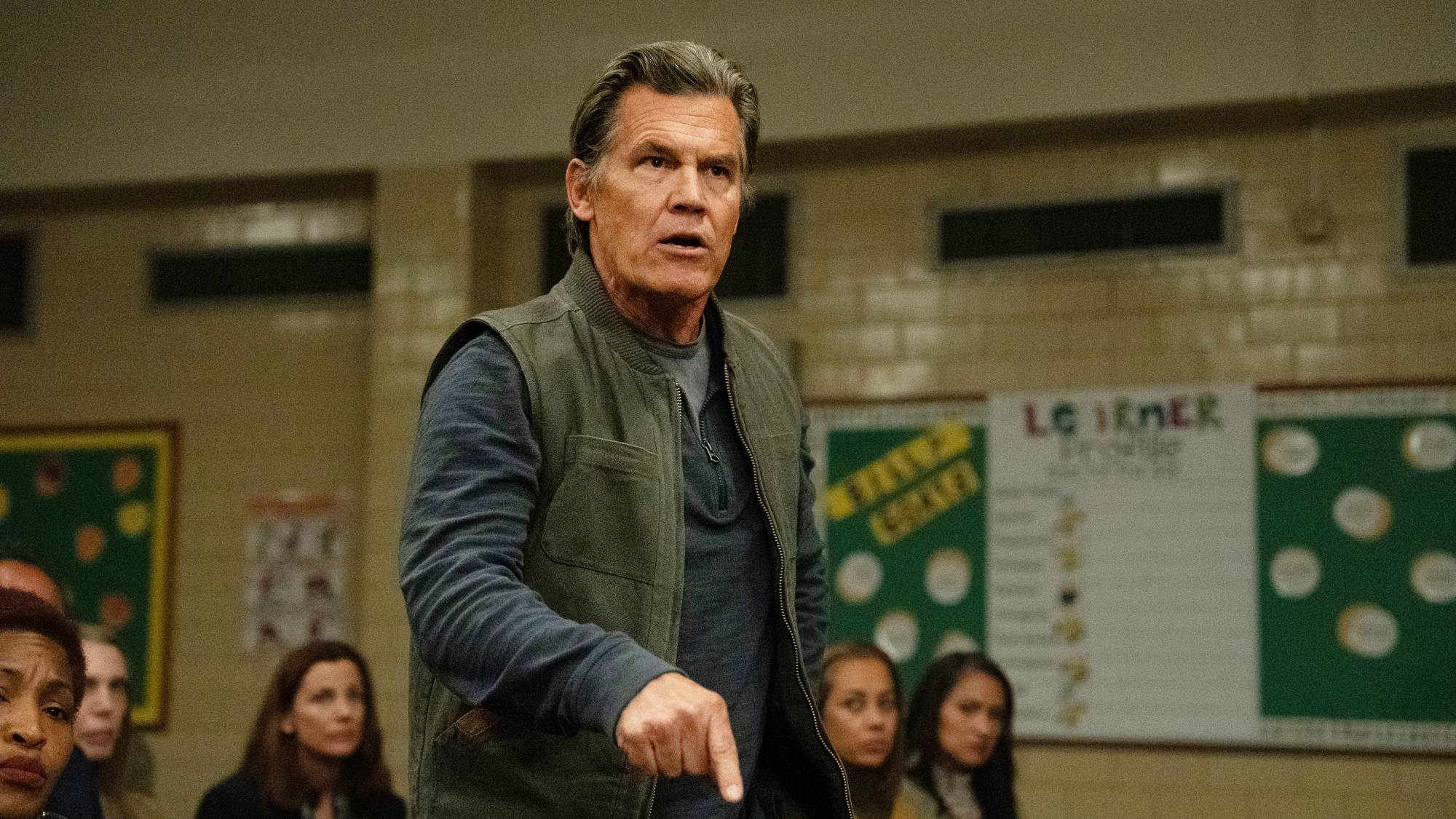

Now, nearly a month after that event, the children still haven’t been located. Archer Graff (James Brolin), the father of one of the pupils, wants to know why Justine hasn’t been arrested. After all, it’s only her class that has vanished; she must know more than she’s letting on!

Archer wants an explanation and so does the film’s audience, but, just as he did in Barbarian, writer/director Creggar refuses point blank to offer a straightforward, linear narrative. Instead, he gives us seven different points of view, allowing us to gradually piece the events together as we are flung back and forth in time.

As well as Justine’s and Archer’s observations, there’s the story of what happens to mild-mannered school principal, Marcus Miller (Benedict Wong); the misadventures of Justine’s old squeeze, police officer, Paul Morgan (Alden Ehrenreich); there’s Paul’s clash with vagrant drug addict, James (Austin Abrams); and, of course, Alex’s account. Dare I mention a propitious visit by Alex’s Great Aunt Gladys (a bone-chilling performance by veteran actor, Amy Madigan), who provides the final piece in the puzzle?

I really can’t say any more about the plot without giving too much away; suffice to say, Weapons is an absolute smorgasbord of delights, by turns poignant, tense, bloody and, in its later stretches, darkly comic. It keeps me enthralled from start to finish and, happily, my initial fears that the central premise would remain unexplained prove to be completely unfounded. The explanation might be as mad as the proverbial box of frogs, but it’s right there, waiting to punch you in the kisser, then run gleefully away with its arms held out at its sides.

If Barbarian was a promising debut, Weapons is proof that horror has a brilliant new exponent. Creggar has created one of the most downright unmissable films of 2025 and I’m already hyped to see whatever he comes up with next.

5 stars

Philip Caveney