16/04/25

Cineworld, Edinburgh

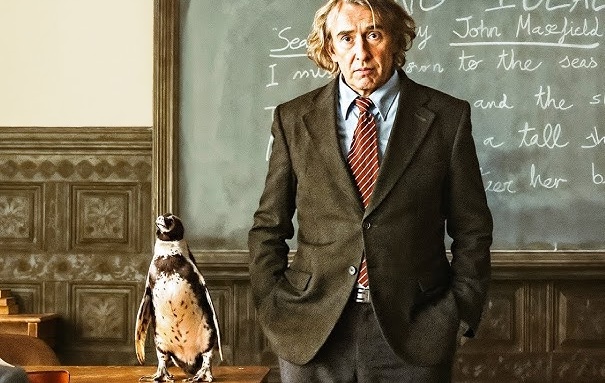

Adapted from Tom Michell’s memoir by the ever industrious Jeff Pope, The Penguin Lessons begins in 1976, when Michell (Steve Coogan) is a somewhat disaffected English teacher, beginning a new post in a private school in Argentina. He arrives in a country that has recently undergone a brutal coup and takes up his post under the watchful gaze of Headmaster Buckie (Jonathan Pryce), a man who prefers to put the needs of the school first and pretend that the current political upheaval is of no consequence. The only friend Tom makes on the staff is Tapio (Björn Gustafsson) a well-meaning but humourless Finlander, who seems to have the knack of saying the wrong thing every time he opens this mouth.

On a brief visit to Ecuador, Tom chances upon a group of oil-covered penguins washed up on a beach. One of them is still alive and – mainly because he’s trying to impress a young (married) woman he’s met in a dancehall – Tom takes the luckless bird back to his hotel room and cleans him up. Having acquired the penguin – Tom dubs him ‘Juan Salvador’ – he finds it impossible to get rid of it, the penguin following him hopefully everywhere he goes. Eventually, Tom has no option but to take Juan Salvador back to the school and keep him hidden in his room… until, in a moment of madness, fuelled by the indifference of his privileged pupils, Tom is prompted to bring the creature into the classroom…

The Penguin Lessons could so easily descend into a mawkish comedy at this point – and there’s no denying that Juan Salvador (or at least the penguin actor who portrays him) is impossibly cute, coaxing adoring sighs from the audience every time he waddles engagingly onto the screen. But Pope’s script skilfully touches on darker themes, dealing with the brutal regime of the Junta and the plight of the ‘disappeared,’ the thousands of people arrested by Perón’s forces. Tom manages to distance himself from the situation until Sofia (Alfonsina Carrocio), the daughter of the school’s housekeeper, Maria (Vivian El Jaber), is arrested on the street and taken away to be ‘interrogated.’

Coogan is on impressive form here, portraying Tom as a cynical, hardbitten loner with something lurking in his past. The short scene where we discover the reason for his remoteness is affecting because it is so understated and yet so utterly believable; likewise, the scene where Tom is prompted to confess to Maria that he could have tried to help Sofia as she was being arrested but was ‘too scared.’

Peter Cattaneo directs with a lightness of touch that effortlessly fuses the film’s disparate elements. There are many who will criticise its ambition but, to my mind it’s beautifully handled: a funny, touching story set against a tumultuous background.

And now, if you’ll excuse me, I’m off to p-p-p-pick up a penguin.

4 stars

Philip Caveney