08/02/26

Cineworld, Edinburgh

I’m a sucker for a modern interpretation of Shakespeare, illuminating the continued relevance of his themes. I’m also a menopausal woman who needs to pee quite frequently, so when I read that Aneil Karia’s Hamlet has a tight sub-two-hour running time, I’m sold. I might actually be able to sit through the whole film!

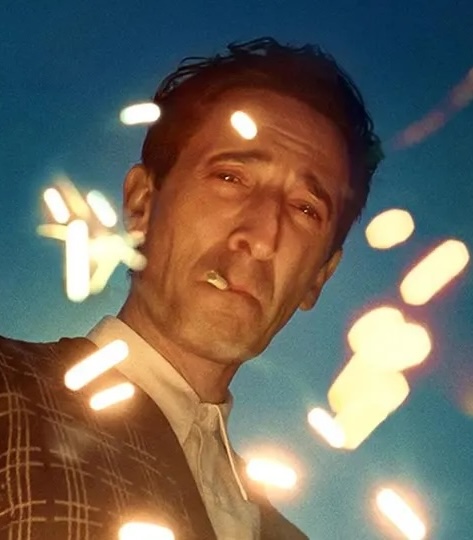

London, 2025. Hamlet (Riz Ahmed) is devastated by the death of his father (Avijit Dutt), the mega-rich owner of a controversial construction company, Elsinore. Numb with grief, the young heir is horrified when his mother (Sheeba Chaddha) announces she plans to remarry without delay – taking Old Hamlet’s brother, Claudius (Art Malik), as her new husband.

As if things weren’t difficult enough, Hamlet soon has a lot more to deal with, when his father’s ghost appears before him, accusing Claudius of killing him and urging his son to seek revenge. True to Shakespearean form, Hamlet devises a convoluted scheme to prove his uncle’s guilt. He’ll pretend to be mad, verbally abuse his girlfriend, and interrupt his mum’s wedding with a play that shows the groom committing murder. What could possibly go wrong?

In this version, Hamlet and his family are British Indians, and we’re in England, not Denmark. In my favourite change to the original, Fortinbras is no longer the defeated King of Norway, but instead the name of a collective of homeless people, who’ve been displaced by Old Hamlet’s cruel business practices. Here, Hamlet’s madness is not just a reaction to his own situation, but a response to the belated realisation that his family’s wealth comes from theft and exploitation. His struggle, in the end, is to restore social justice, as well as to avenge his dad.

There’s a lot to like about this film. It’s exciting and propulsive, stripping Hamlet down to its most interesting parts, while retaining enough soul-searching to make us understand the young protagonist’s despair. I love the depiction of the players’ performing Old Hamlet’s murder, and the famous soliloquy (“To be or not to be…”) is utterly thrilling, as Hamlet – driving through London’s busy night-time streets – floors the accelerator and takes his hands off the steering wheel…

I’m not sure that the omission of Horatio works particularly well: the contrasting counsel of Horatio and Laertes (Joe Alwyn) adds an interesting dimension to the play that is lacking here. I also think that, in a contemporary adaptation such as this, Ophelia (Morfydd Clark) could be given more to do. On the other hand, I like the subtle changes to Gertrude’s character, cleverly rendering her innocent of any crime while also giving her more agency. Chaddha’s performance is nuanced and convincing – and Timothy Spall was surely born to play Polonius.

But this is Riz Ahmed’s film, and he’s as fine a Hamlet as I’ve ever seen: a flawed young man tormented by grief and guilt, behaving badly and impulsively, hurtling towards his own demise. It’s a tale as old as, well, four hundred years. And still it endures.

4 stars

Susan Singfield