04/03/36

Traverse Theatre, Edinburgh

Jack (Jonathan Watson) and Kathy (Maureen Carr) are recording an online chat with their granddaughter, Molly, providing her with some recollections she might be able to use in a school project that’s looking for ‘untold Scottish stories.’ Their separate reminiscences take them both back to the long hot summer of 1976, when they set off on their first ever holiday – two years after a rushed marriage, when Kathy fell unexpectedly pregnant.

In the van that Jack borrows from work, they drive to Campbeltown near the Mull of Kintyre. Jack has a hidden agenda. He’s been a rabid Beatles fan ever since he first heard the strains of Love Me Do, and now he’s nurturing a powerful compulsion to visit the secluded cottage where he knows his hero, Paul McCartney, has been spending much of his time since the world’s most famous band went their separate ways…

This first production in the new season of A Play, A Pie and a Pint, written by Milly Sweeney, is apparently based on a true story. It’s a lighthearted, whimsical piece, deriving much of its humour from the ways in which the memories of the two contributors differ in so many important aspects. The constant cross-cutting between them is the basis of the drama but the couple’s banter is not always as precise as it be and I’m left with the feeling that this piece could have benefitted from a little more rehearsal time.

There’s an attempt to draw comparisons between the break up of the Fab Four and the disintegration of Jack and Kathy’s relationship, a central premise that occasionally feels a little too forced for comfort – but I do like the fact that the play readily accepts that not every marriage is destined to last forever, a touch of realism so often lacking in drama.

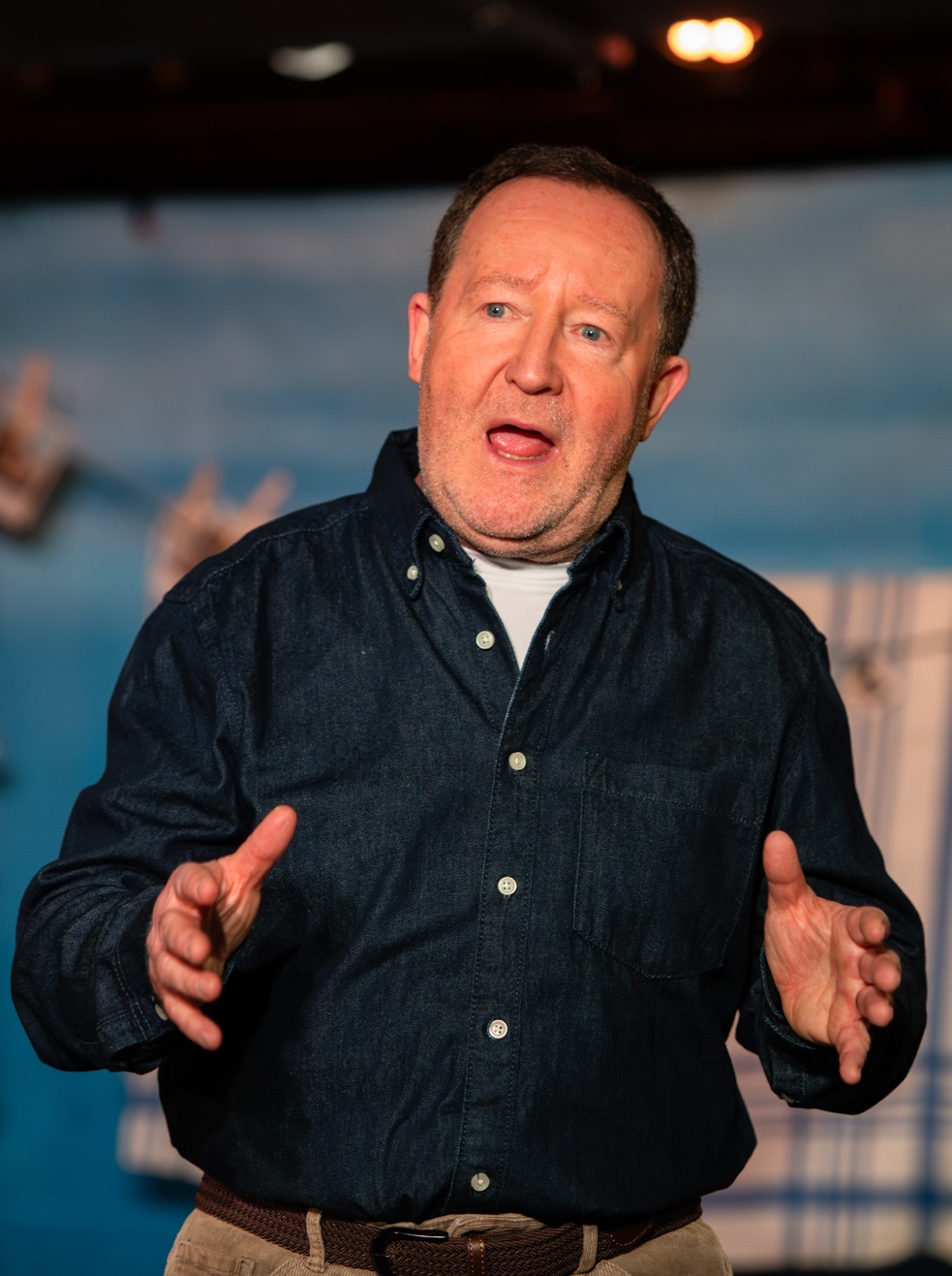

Both Watson and Carr are familiar performers at PPP and both are appealing in their respective roles. Sally Reid directs the piece with a light touch and Heather Grace Currie’s simple set design successfully evokes the era. The image of a postcard – which is an important element in this supposedly true recollection – is occasionally illuminated in the background.

Someone’s Knockin’ on the Door provides a charming, if innocuous, opening to the new season – I do however occasionally find myself wishing for a little more grit in the telling.

3.4 stars

Philip Caveney