Another varied year of theatre-going presents us with the usual problem of choosing what we think were the twelve best shows of the year. But once again, here they are in the order we saw them.

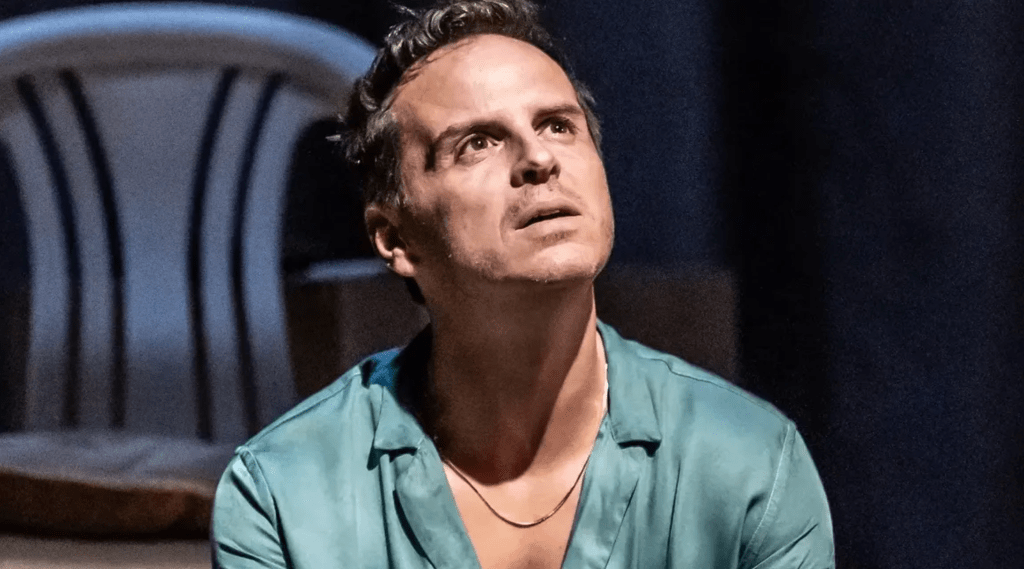

Vanya (National Theatre Live)

“Glides like gossamer through the cuts and thrusts of a family drama – even a scene where Scott is obliged to make love to himself unfolds like a dream…”

Dr Strangelove (National Theatre Live)

“This brilliantly-staged production is a weird hybrid – part play, part film – and at times astonishing in its sheer invention…”

Wild Rose (Lyceum Theatre, Edinburgh)

“A fabulously entertaining story about ambition and acceptance, anchored by a knockout performance from Dawn Sievewright…”

Chef (Traverse Theatre, Edinburgh)

“Sabrina Mahfouz’s Chef is an extraordinary play, a monologue delivered in a lyrical, almost poetic flow of startling imagery…”

Lost Lear (Traverse Theatre, Edinburgh)

“Dan Colley’s beautifully-conceived script intertwines excerpts from Lear with moments in the here and now, gently but relentlessly uncovering the horrors of cognitive decline…

Alright Sunshine (Pleasance Dome, Edinburgh)

“Directed by Debbie Hannan, Cowan’s taut, almost poetic script is brought powerfully to life by Geddes’ mesmerising performance: a tour de force with real emotional heft…”

A Streetcar Named Desire (Lyceum Theatre, Edinburgh)

“Eschews the victim-blaming that so often blights interpretations of this play and turns up the heat on the sweaty, malevolent scenario, so that the play’s final half makes intense, disturbing viewing…”

Common Tongue (The Studio at Festival Theatre, Edinburgh)

“A demanding monologue, Caw’s performance is flawless, at once profound and bitingly funny: the jokes delivered with all the timing and precision of a top comedian; the emotional journey intense and heartfelt…”

Little Women (Bedlam Theatre, Edinburgh)

“Watching events play out, I feel transported back into the cocoon of my childhood, curled up in bed reading about these faraway adolescents and their travails…”

The Seagull (Lyceum Theatre, Edinburgh)

“There’s so much to enjoy here and not just Quentin’s perfectly-judged performance as the conceited, self-aggrandising Irina, intent on making every conversation all about her…”

Wallace (Traverse Theatre, Edinburgh)

“Whip-smart, caustically funny and actually pretty informative (I come out knowing a lot more about the titular Scot than I previously did), Wallace snaps from song to song and from argument to argument like the proverbial tiger on vaseline…”

Inter Alia (National Theatre Live)

“Doesn’t offer any easy answers or let anyone off the hook, but expertly straddles the fine line between trying to understand assailants without diminishing their victims…”

Susan Singfield & Philip Caveney