22/08/25

Assembly George Square (Studio 3), Edinburgh

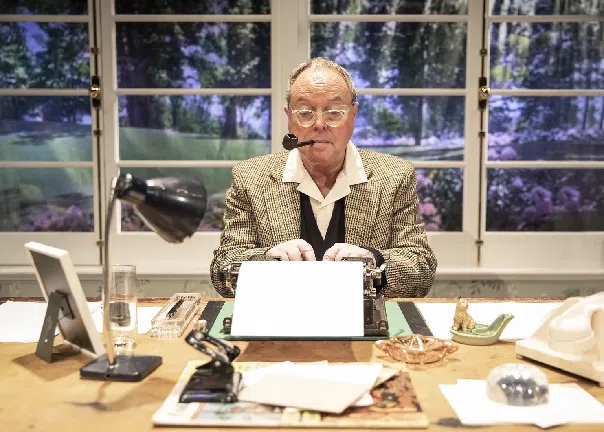

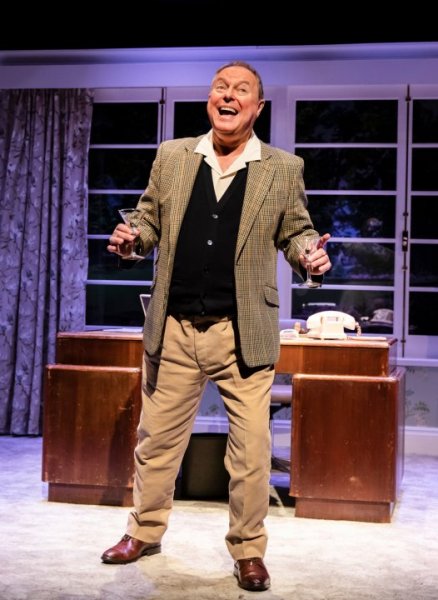

Not so much an impersonation as a celebration, Robert Daws is clearly having a whale of a time in William Humble’s Wodehouse in Wonderland, and, after a few minutes of uncertainty while I tune in to the tone of the piece, so am I. Wodehouse is, of course, one of those writers who almost defy belief: incredibly prolific, very successful in his own lifetime – but remembered now for the accusations levelled at him for his ‘collaboration’ with the Nazis during World War Two.

We meet him in the 1950s, living in exile in Long Island and reluctant to return to his British homeland. He’s still writing fiction (though a book now takes him six months rather than three) and he’s also hankering after another shot at writing for the theatre with his old partner, Guy Bolton, who lives nearby.

Daws offers a relaxed and jovial performance as Wodehouse, mixing martinis as he talks, expressing his intense dislike for the great Russian authors (too gloomy) and making slyly humorous observations about his wife, Bunny’s profligacy. He also speaks lovingly about his adopted daughter, Leonora – or ‘Snorkles’ as he prefers to call her – who he claims is his ‘Number 1 critic.’

He talks – with great reluctance – to his American biographer, who eventually nudges him in the direction of that unfortunate business with the Germans… and, lest the tone grow too serious, every so often, Daws interrupts proceedings to launch into a rendition of one of the author’s comic songs.

Wodehouse in Wonderland is a revelation in many ways. I was a fan of Jeeves and Wooster back in the day and read several of their adventures when (just like Wodehouse in his youth) I was sequestered in a rather unpleasant boarding school. I learn quite a lot about the author over the hour and realise that I have been misinformed about that ‘collaboration’ business – so it’s nice to have the record set straight.

Towards the conclusion, there’s also a moment of sweet sadness, which Daws handles with absolute assurance. While this may be best suited to those familiar with Wodehouse’s work, it’s not essential. Those looking to spend a pleasant and rewarding hour on the Fringe should find plenty here to keep them thoroughly entertained.

4.4 stars

Philip Caveney