20/05/23

Apple TV

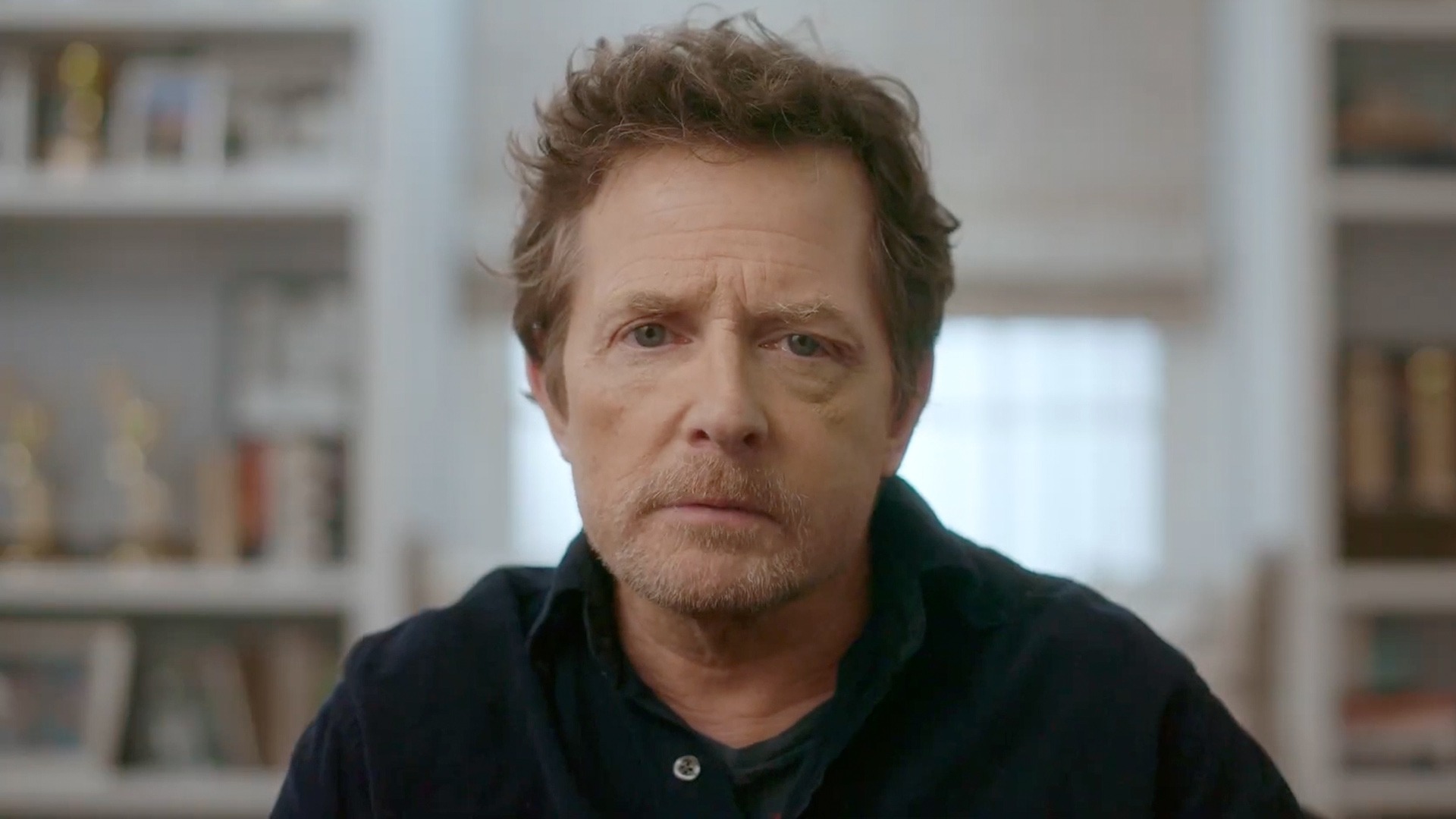

The name Michael J Fox is synonymous with three things: Marty McFly; a teenage, basketball-playing werewolf; and Parkinson’s disease. Mega-famous in the 1980s for smash hit films Back to the Future and Teen Wolf, Fox is just as well-known these days for his candid communications about living with a degenerative brain disorder. This inventive documentary, by Davis Guggenheim, is revelatory – about Fox, as well as about Parkinson’s.

Fox has always exuded on-screen warmth. He’s the epitome of likeable: wry, self-deprecating and funny. Whatever role I’ve seen him in, he brings these qualities to bear. Watching Still, it soon becomes apparent that that’s just who he is, which isn’t to denigrate his acting ability: he’s played a range of types – but always with a hint of sweetness shining through.

Guggenheim’s biopic is thoughtful and meandering, cutting between past and present, making clever use of film clips to illustrate key details of Fox’s life and character. From tiny live-wire working-class Canadian kid to tiny live-wire Hollywood star, we see how Fox’s kinetic energy (and general niceness) propelled him to success. It also enables him to live contentedly: unusually for someone in his career, he’s sustained a long and happy marriage and is clearly close to his four kids. Fox’s wife, Tracy Pollan, is an actor too (they met on hit TV show Family Ties) and the pair seem truly devoted. It’s lovely to see.

In some ways, the film is harrowing, because it doesn’t pull any punches about the realities of living with Parkinson’s. Fox falls over a lot and hurts himself when he lands: he’s broken all the bones around his left eye. He shakes uncontrollably, all the time; he struggles to walk. He relies on medication, very aware of when it’s wearing off and he needs his next pill. He has a lot of physio, which helps to keep him mobile. Presumably Parkinson’s sufferers without his kind of money can’t access quite so much one-to-one therapy; even with it, things are tough.

But in other ways, the film is uplifting, because – while it steadfastly avoids the ‘disabled person as inspiration’ trope – it also shows how the condition doesn’t really change the man. Michael is still very much Michael, with the same twinkle, the same humour, the same candour.

It’s fascinating to listen to him describe the tricks he employed in the early days of his diagnosis (aged only 29), when he was desperate to hide his tremors from the world. Once you know what he’s doing, footage from Spin City, the TV show he was making back then, takes on a whole new significance.

Still is a weirdly feelgood film – a testimony to a life well-lived.

4.6 stars

Susan Singfield