14/02/26

Traverse Theatre, Edinburgh

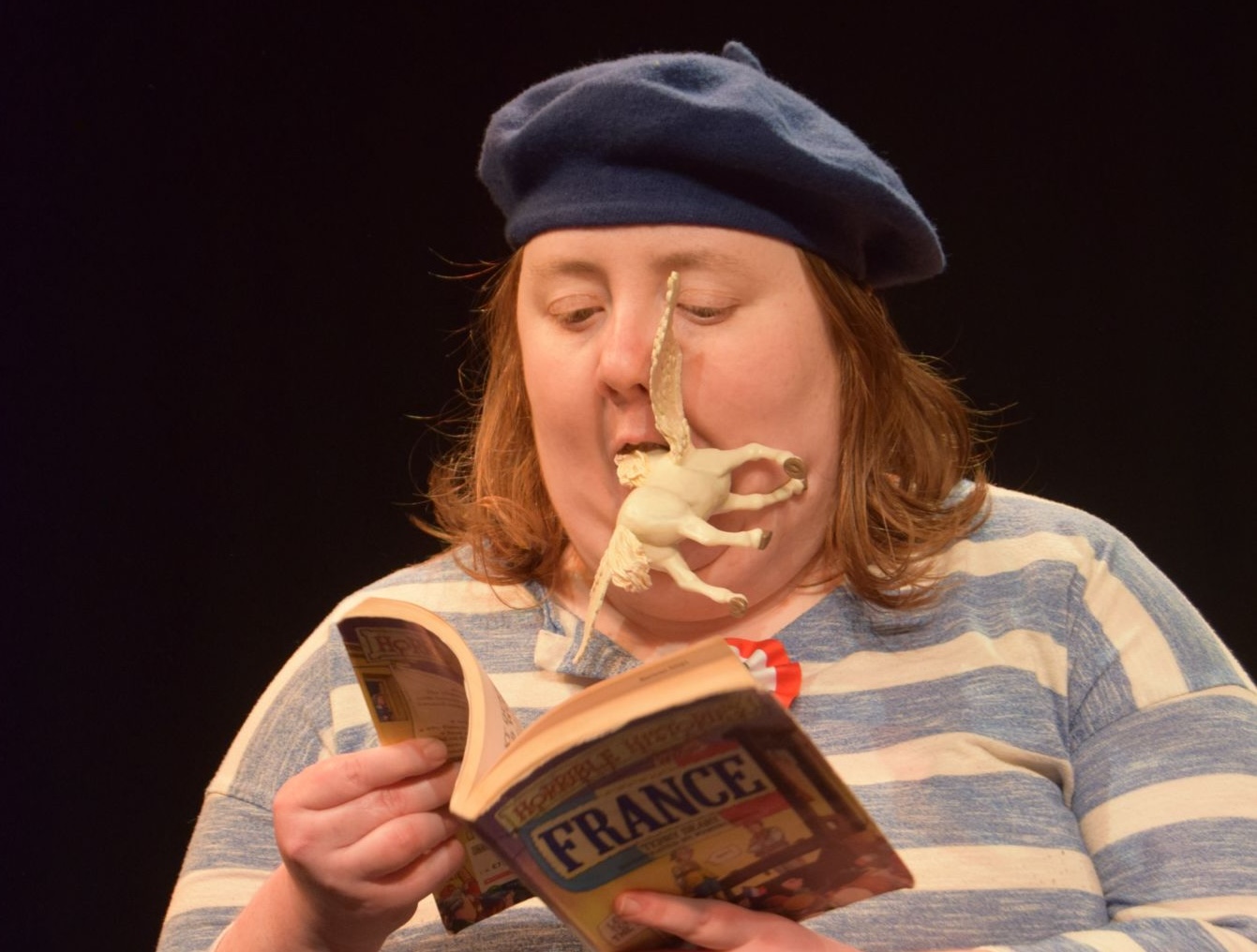

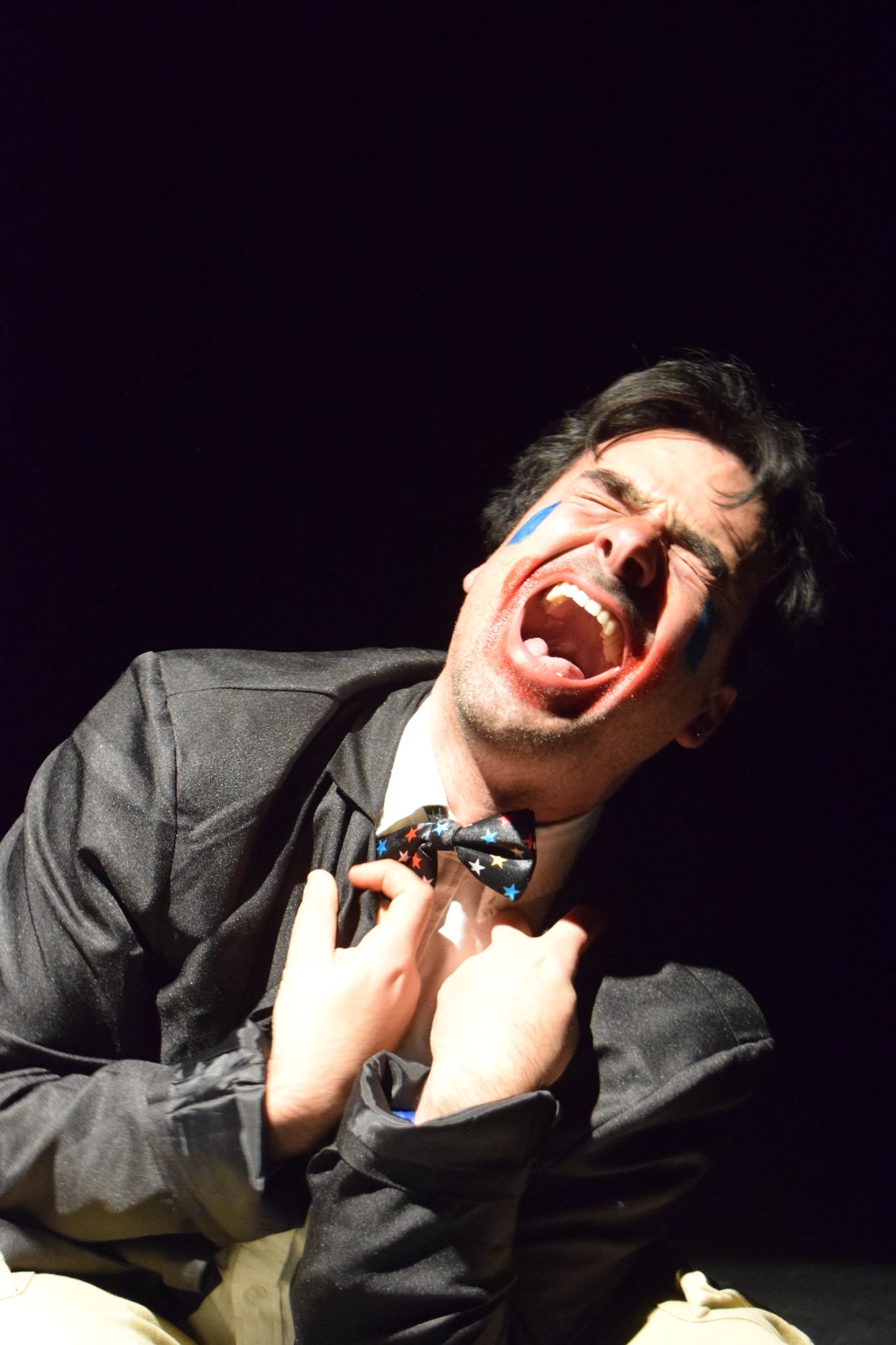

The Flames is a Tricky Hat Theatre Company for over 50s – and it’s a glorious example of the merits of community theatre. Here, twenty-two amateur performers gather to share their stories, which are then shaped into a cohesive series of vignettes by professional directors, Fiona Miller and Scott Johnston. As an audience member, I find it powerful and life-affirming. For the participants, I’m sure it’s potently therapeutic.

Thanks to choreographer Laura Bradshaw, the piece eddies and flows in a way that feels almost elemental. Set to Malcolm Ross’s gentle score, performed live on an electric guitar, the movement is precise and careful. It’s also wild at times, as varied as the tide. I especially like the super-slow-mo section – where one actor is speaking centre-stage and the others are placing their chairs and sitting on them so gradually that the motion is barely discernible – followed immediately by a change of pace, as the actors rush to surround the speaker.

The stories are short, focusing on those small moments that make a life. Love, loss, outrage, joy – they’re all here. One woman remembers a hat that saves her from falling cicadas, another a psychopath who declared his love. A widow asks if we believe in love at first sight, and recalls the day she met her husband. A shell-shocked man tells us about his wife’s cancer diagnosis. We hear about sibling rivalry, domestic violence, fun days out and so much more. Even within this not-very-diverse looking ensemble, there are myriad experiences.

The production levels are high – this is a polished and impressive piece of theatre – thanks in no small part to Kim Beveridge’s digital design. Projected onto the backdrop is monochrome video footage of the performers: sometimes in extreme close-up, highlighting their emotions; sometimes mid-shots, focusing on the bonds that have formed between them.

This is am-dram with a difference, deeply personal and beautifully crafted.

4 stars

Susan Singfield