14/04/22

Mareel, Lerwick, Shetland

When we book our tickets for the The Hermit of Treig, it seems very fitting: we’ll be watching a documentary about a recluse living in a remote Scottish location, while we’re in a remote Scottish location! Such perfect symmetry! And it’d be a good idea, if it weren’t for the fact that Mareel – despite being the UK’s most northerly music, cinema and creative industries centre – doesn’t feel remote at all. It’s a bustling, vibrant place, and the Thursday evening showing is all but sold out.

Not that we’re complaining. We feel right at home. (In fact, Mareel is very much like HOME, one of our favourite Manchester venues). We sit in the sun-soaked, glass-walled bar for an hour before showtime, sipping beer and Prosecco, enjoying the buzz. The staff are friendly and the place pristine. It’s a real find.

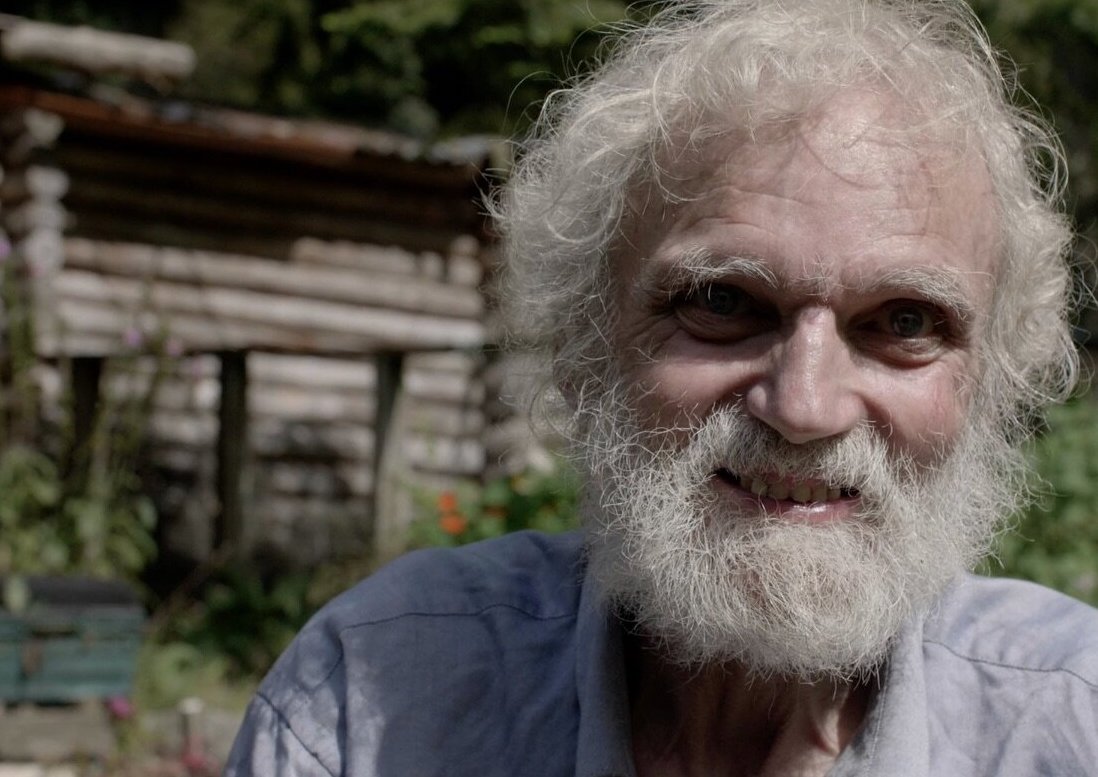

And Lizzie MacKenzie’s debut film is a find too. She’s spent ten years following Ken Smith, the eponymous hermit. And, over those years, a real friendship seems to have emerged. He may have turned his back on civilisation, but he’s an amiable sort: chatty and engaging and happy to share his musings.

When he was twenty-six, Ken was viciously attacked, and suffered a brain haemorrhage as a result. His doctors feared he would never speak or walk again. But Ken pulled through and, as soon as he was well enough, he set off to live his life on his own terms. He went to Canada and lived wild in Yukon for a few years, before returning to the UK and heading north to Scotland. He walked the length and breadth of the country he says, before finally deciding to stay put near Loch Treig. And this is where the young film-maker finds him, living off-grid in a home-made wooden cabin, far far from any beaten track, foraging for food and revelling in his splendid isolation.

It’s a lovingly crafted film, with a tender heart; it’s easy to see why MacKenzie won the audience award at this year’s Glasgow Film Festival. It’s not just the cinematography (MacKenzie’s) and photography (Smith’s) that dazzle with their natural beauty; the documentary shimmers with kindness and humanity too. Ken is seventy-two years old now. He’s not as strong as he was. He’s had a stroke. How long will he be able to manage?

It’s heart-warming to see the local (okay, local-ish) community rally round. Everyone’s so respectful of Ken’s way of life. They try to help him, but they don’t dictate; they don’t attempt to change him. And Ken’s pretty accepting too: hopeful that he’ll be able to continue living independently in his beloved hut, but pragmatic about the possibility that he might not.

There are some gaps in the narrative that I’d like explained. Is Ken allowed to just build a home in the woods? How does he get his photographs developed? What was the story behind his first cabin being destroyed? There are tantalising hints at avenues left unexplored.

Still, just like Mareel, The Hermit of Treig isn’t what we expect. And, like Mareel, that’s absolutely a good thing.

4 stars

Susan Singfield