08/12/23

Cineworld, Edinburgh

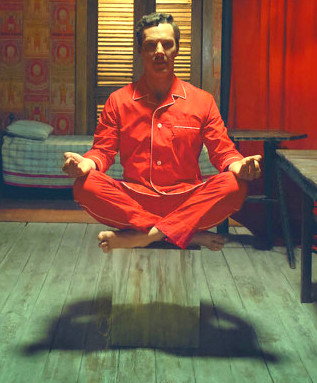

The omens were always good for Wonka. Director Paul King and writer Simon Farnaby have already delivered two brilliant (5 star) Paddington films, but were willing to assign the upcoming Paddington in Peru to other hands in order to focus on this origin tale based around Roald Dahl’s most celebrated character. What’s more, Timothée Chalamet – who seems to have the uncanny ability to choose box office winners with ease – was signed up for the title role right from the very beginning.

And sure enough, Wonka turns out to be as sure-footed as you might reasonably hope, powered by a deliciously silly story and some sparky songs by Neil Hannon, plus a couple of bangers salvaged from the much-loved 1971 film starring Gene Wilder. Laughter, music and magic: they’re all here in abundance.

In this version of the tale, the young Willy Wonka arrives in a city that looks suspiciously Parisian (but is actually Oxford). His masterplan is to pursue an ambition he’s had since childhood: to create the world’s most delicious chocolate.

Armed with an original recipe from his late mother (a barely glimpsed Sally Hawkins) and augmented by some magical tricks he’s picked up along the way, Wonka has mastered the chocolatier’s arts to the final degree, but has somehow neglected to learn how to read. Which explains why he soon ends up as a prisoner, working in a hellish laundry run by Mrs Scrubbit (Olivia Colman, for once playing a convincingly loathsome character) and Mr Bleacher (an equally odious Tom Davis). It’s here that Wonka acquires a small army of workmates, including Noodle (Calah Lane), a teenage orphan who has mysterious origins of her own and who soon proves to be Wonka’s most valuable ally.

When he’s eventually able to sneak out and pursue his main goal, he quickly discovers that the local chocolate industry is dominated by three powerful and devious men, Slugworth (Paterson Joseph), Prodnose (Matt Lucas) and Fickelgruber (Matthew Baynton), who are willing to go to any lengths to protect the stranglehold they currently enjoy. They see Wonka as a potential threat and will stop at nothing to eliminate him…

Mostly, this works a treat. Chalamet is an astute choice for the lead role, capturing the man-child quality of young WW, whilst still managing to hint at the darker elements that lurk deep within him. Lane is suitably adorable and, if the triumvirate of evil chocolate barons never really exude as much malice as you’d like, it’s no big deal. The only real misstep is the fate of the local police chief (played by Keegan Michael-Key), who takes bribes in the form of chocolate and who steadily puts on more and more weight, until he’s almost too big to fit in his car. While this fat-shaming device may be true to the ethos of Mr Dahl, it feels somewhat out of place in a contemporary story.

And of course this being a Wonka tale there must be Oompa-Loompas, played here by an orange-skinned, green-haired Hugh Grant, who is wonderfully pompous and self-possessed, yet somehow manages to be quite adorable at the same time. As you might guess, Mr Grant is obliged to dance (again), something he allegedly hates doing. He’s used sparingly through the film but still nearly manages to steal it from under Chalamet’s nimble feet.

All-in-all, Wonka is an enjoyable family film, as bright, glittering and irresistible as a bumper hamper packed with tasty treats. It’s interesting to note, however, that I didn’t come out of this feeling like tucking into some. On the contrary, a scene where Willy and Noodle find themselves drowning in a big vat of molten chocolate actually has me feeling faintly queasy.

Nonetheless, those seeking an enjoyable couple of hours at the cinema, could do a lot worse than buying a ticket for this delightful offering, which will appeal to viewers of all ages.

4.4 stars

Philip Caveney