09/12/20

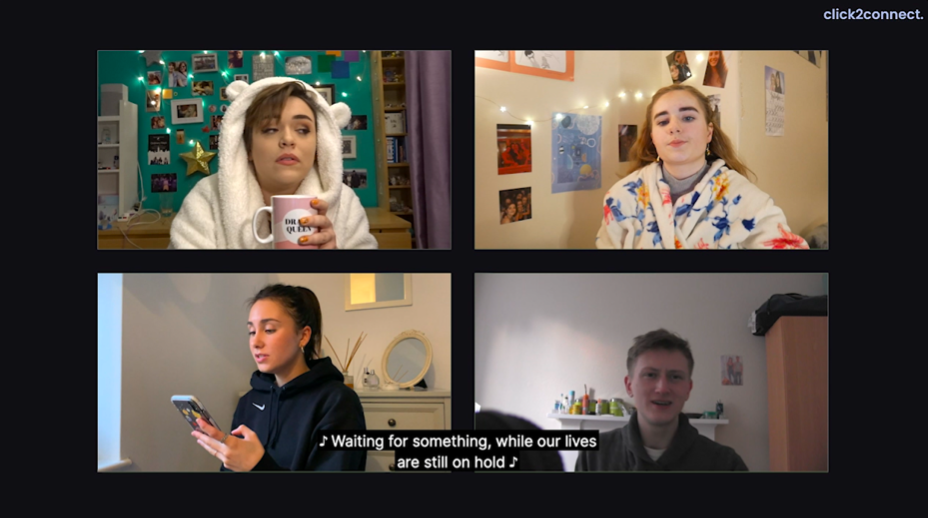

We’ve seen many enjoyable musicals from this talented student company over the years, but in 2020 – for pretty obvious reasons – they’ve had to make some radical adjustments to their usual approach. With all the cast members stuck in their own spaces, they’ve decided to embrace those limitations and the result is Click To Connect, an original play/movie musical filmed as a series of Zoom meetings. If this sounds underwhelming, don’t be misled. Others have tried this approach and foundered, but I’ve rarely seen the format appropriated with such brio.

The script, co-written by no less than five authors, concentrates on four relationships. Amy (Lucy Whelan) has recently broken up with her long time boyfriend and is now living with her parents. She contacts her friend, Sam (Nicola Alexander) and confesses the real reason why she is now single. Lex (Annie Docherty) and Kelsea (Leonie Findlay) are ex-partners, who’ve set up a double-date with their respective new interests, Mia (Kristen Wong) and Tom (Attir Basri) but, once the chat is underway, things don’t quite go to plan. Finally, Sadie (Rachel Cozens) is living away from her husband, George (Sebastian Schneeberger), and things have gone somewhat awry. Can their once-strong relationship be salvaged?

There are some breezy, melodic pop songs to kick things into action and nicely judged performances from Whelan and Alexander provide the piece’s strongest moments. I also love the way that Zoom’s limitations are cannily incorporated into the storyline – a warning that we are going to be kicked off after a set time (because we haven’t paid to use the service for longer than 40 minutes) is deftly employed and there’s even an attempt to simulate the inevitable dodgy wi-fi signal for one character.

Click to Connect is a timely example of how artistic ingenuity can overcome severe limitations and EUSOG have certainly risen to the challenge with aplomb. Of course we all look forward to the times when we can head back to the Pleasance to watch their next venture, but until then, this will do nicely.

4 stars

Philip Caveney