22/11/25

Cineworld, Edinburgh

It’s 1945 and, in the midst of the chaos following the end of World War 2, Reichsmarshall Herman Göring (Russell Crowe) surrenders to American troops (although he makes it blatantly clear that he still expects them to carry his suitcases). When the news reaches United States Supreme Court Justice Robert Jackson (Michael Shannon), he begins to draw up plans for an International Military Tribunal, which will charge Göring and other surviving Nazi leaders with war crimes – and what better place to enact this than in the venue where the late Adolf Hitler held his infamous rallies in the 1930s?

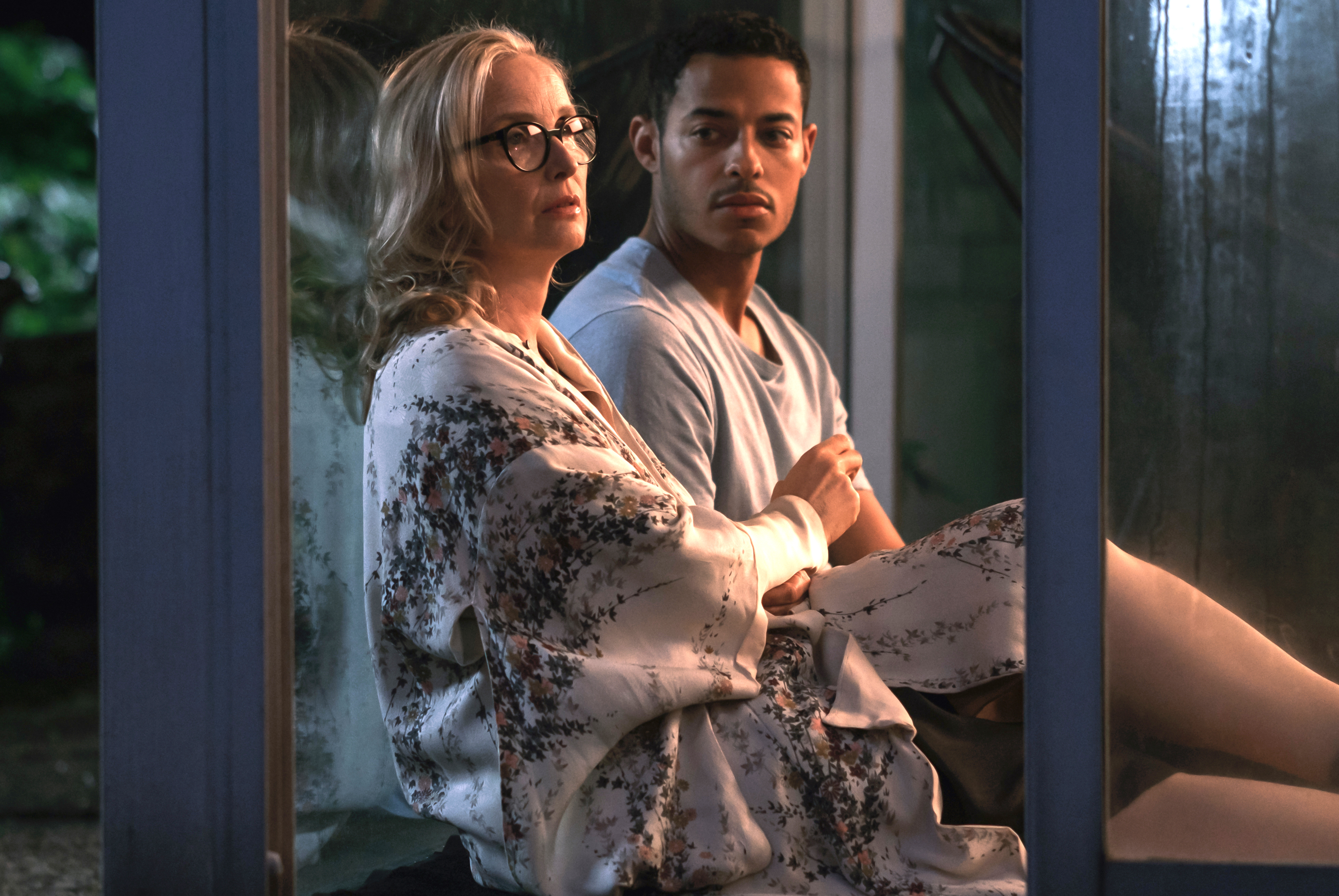

Jackson takes a leave of absence from the supreme court and meets up with British prosecutor, Sir David Maxwell Fyfe (Richard E. Grant), who will assist him in trying the case. He also enlists the services of army psychiatrist, Douglas Kelly (Rami Malek), who – assisted by German-English translator, Sergeant Howie Triest (Leo Woodall) – will attempt to get to know Göring and the other captured Nazi leaders before the trial begins. Maybe the old proverb about knowing your enemies will be useful. Besides, Kelly has ideas about writing a best-selling book afterwards.

He begins to make progress with Göring and tells himself that the two of them have established the basis of a genuine friendship – but he will come to learn that Göring has his own agenda…

Nuremberg, written and directed by James Vanderbilt, has some big boots to fill. Many people remember Stanley Kramer’s 1961 movie, Judgement at Nuremberg, long regarded as a cinematic milestone – and I have to admit that, based on his recent screen outings, I have big doubts about Russell Crowe taking on such a difficult role. So I’m both surprised and delighted to say that I’m impressed by the film and by Crowe’s performance which captures Göring’s smirking, confident persona with genuine skill. Shannon is quietly magnificent in his role and Grant is handed a fabulous cameo courtroom scene, which he handles with his usual aplomb. Malek is often accused of over-acting but he does a good job here too, showing how Kelly’s ambitions destroy his own future.

I won’t pretend that this is an easy watch. The latter stages of the trial include the showing of genuine footage from concentration camps and there’s been no attempt to soften or obscure the devastating images they contain. I spend much of the film fighting back tears as I watch the horrors unfold. But the scenes are shown so unflinchingly to make a really important point: that the evils that men do are not carried out through devotion to a cause, nor for the greater good of the world. Such crimes are enacted because of greed, and because there are people who see such brutality as merely a means to an end, a way to further their own unspeakable agendas.

So my advice would be to steel yourselves and go and see Nuremberg. Then think about where the world is now – and how perilously close we are to allowing such horrors to proliferate once again.

4.4 stars

Philip Caveney