20/03/25

Lyceum Theatre, Edinburgh

Rose-Lynn Harlan (Dawn Sievewright) has a dream: to appear on the stage of Nashville’s legendary Grand Ol’ Opry, belting out a country song – not a country and western song, mind you. It’s an important distinction. So, being banged up in prison for a year wasn’t part of the grand ol’ plan – but now she’s served her time and is finally able to head back to her mum, Marion (Blythe Duff), who has been dutifully looking after Rose-Lynn’s two young children, Lyle (Leo Stephen) and Wynonna (Jessie-Lou Harvie).

Rose-Lynn is dismayed to find that her kids have become disaffected by her long absence and that their former trust in her has been all but eroded. What’s more, they view her long-cherished dream as selfishness. And that’s not all that has changed. When she calls in at the Grand Ol’ Opry, Glasgow – where she previously had a residency – she discovers that her regular slot has been handed to the dreaded Alan Boyne (Andy Clark), a long-haired carpet fitter with a sideline as a charisma-free country singer.

Desperate to keep her head above water, Rose-Lynn takes a part-time post as a cleaner, working for the highly-privileged Susannah (Janet Kumah). She’s a go-getter and, once she’s heard Rose-Lynn sing, she becomes determined to put her in touch with legendary DJ Bob Harris, who Susannah believes might be able to offer some good advice.

Rose-Lynn realises that her long-cherished ambitions are still burning as fiercely as ever…

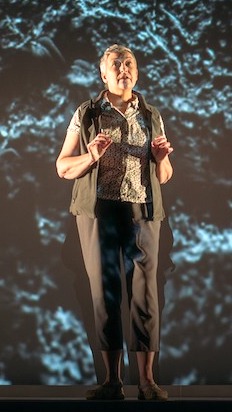

This assured version of the 2018 film (adapted by its original screenwriter, Nicole Taylor) makes a seemingly effortless transition to the stage. A prison-set opening where Rose-Lynn and her fellow inmates launch headlong into a propulsive rendition of Country Girl sets the tone perfectly, with Sievewright stepping into Jessie Buckley’s cowboy boots with absolute authority. An eight-piece band ranged across the back of the stage performs a varied selection of numbers, from banging rockers to lilting, steel-guitar layered ballads. And it’s not just Sievewright supplying the singing.

As bar-owner, Jackie, Louise McCarthy belts out her own fair share of raunchy vocals, Duff does a fabulous job with a haunting song of regret and even the two youngest members of the cast have the opportunity to shine as vocalists. Clark – who takes on a number of roles – proves himself an invaluable asset to the production, as does Hannah Jarrett-Scott, who appears as two (very different) characters.

Chloe Lamford’s simple but effective set design works beautifully alongside Jessica Hung Han Yun’s inventive lighting and Lewis den Hartog’s simple-but-effective video design. John Tiffany handles the directorial reins with absolute aplomb. It’s worth mentioning, I think, that Wild Rose will be the final production under David Greig’s eight-year spell as the Lyceum’s artistic director. He leaves on an impressive high note.

Wild Rose is a fabulously entertaining story about ambition and acceptance, anchored by a knockout performance from Dawn Sievewright. Anyone in search of an uplifting night at the theatre will find it here. And you don’t have to be a die-hard country fan to enjoy this fabulous show.

5 stars

Philip Caveney