30/03/25

The Cameo, Edinburgh

Joshua Oppenheimer might not be the most prolific of directors, but he’s certainly one of the most original. The documentary-maker’s first foray into fiction is a case in point: who else would offer us an unsettling post-apocalyptic… musical?

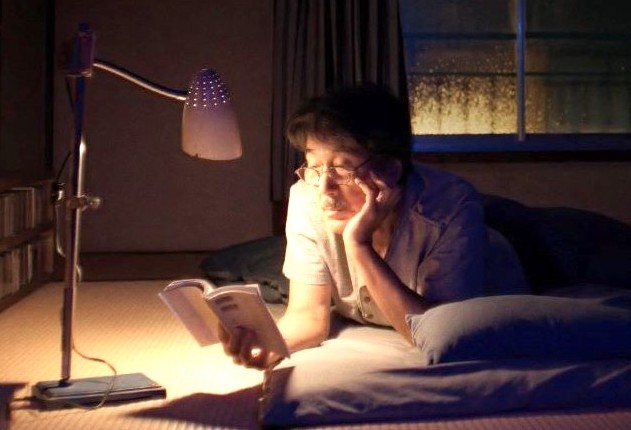

The setting is an oligarch’s nuclear bunker. There’s been some kind of climate disaster, precipitated by the billionaire’s fossil fuel company. Most of humanity is dead, but – decades after the fallout, far below the earth – a chosen few still live in luxury, albeit in the confines of some eerie salt mines.

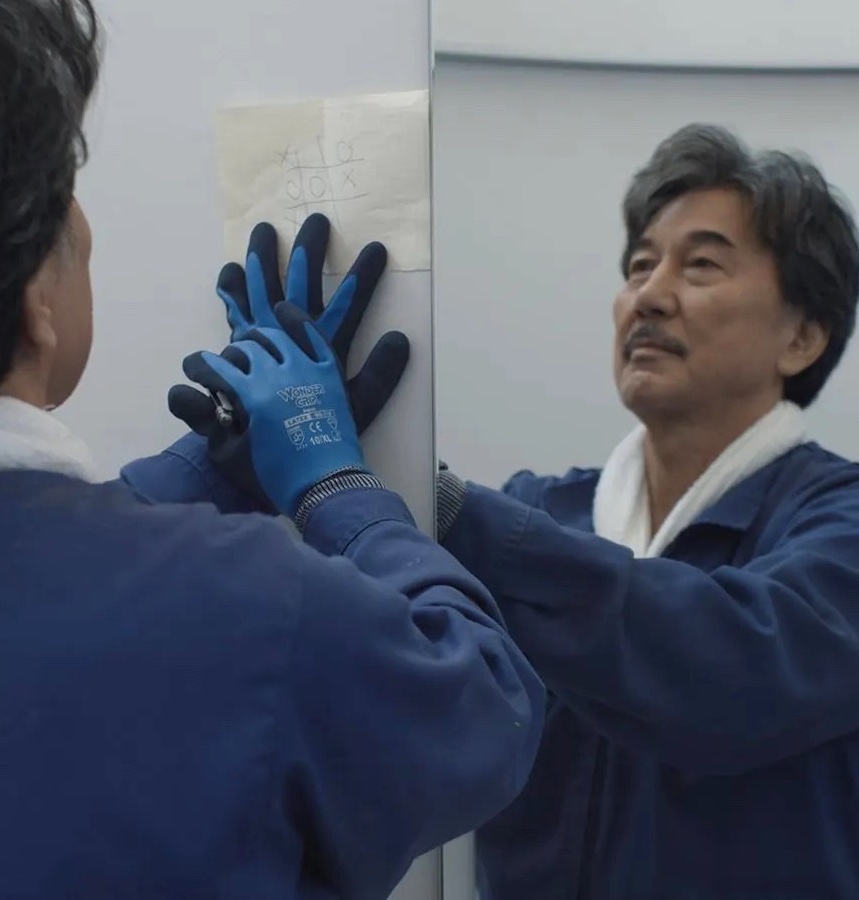

Father (Michael Shannon) is the oligarch, Mother (Tilda Swinton) his wife and Son (George McKay) their twenty-year-old child, born underground. He has never seen the sky, never met anyone outwith their small circle – and never questioned his parents’ tales about their former lives. Instead, he immerses himself in building an intricate model of all the outside places he’s only ever heard about.

The bunker has three more occupants: Friend (Bronagh Gallagher), Butler (Tim McInnerny) and Doctor (Lennie James). The trio are touted as “part of the family” but it’s pretty clear they’re here to serve, to take care of the cooking, the cleaning and the rich people’s health. Father spends his time working on a self-aggrandising autobiography, resisting Son’s attempts to offer editorial advice, while Mother fusses endlessly over the exact positioning of the priceless artworks on the walls. Life ticks by, one day much like another, an opulence-clad monotony that fulfils none of them.

And then Girl (Moses Ingram) turns up. She’s the first outsider Son has ever met, and he’s smitten. But she’s had to leave her family behind, and her survivor’s guilt opens up new avenues of thought for Son. Why has his family been chosen, out of everyone, to inhabit this haven? And why, when the place is vast, are there so few of them? Once he starts to ask questions, everything changes…

Mikhail Krichman’s cinematography is sumptuous: the scenes in the salt mines are particularly beautiful, but every shot is a work of art, as meticulously framed as the Renoirs and Monets decorating the bunker.

The film is billed as a musical but, despite the lengthy spoken sections, it feels more like an opera, with its formality of tone and portentousness. The music by Marius De Vries and Josh Schmidt amplifies the heightened emotions, but the vocal parts are sensibly kept simple, which suits the non-singers in the cast (such as Swinton). Ingram, Gallagher and McKay are more accomplished, and they are given the most to do.

Despite its bloated running time, The End is a thought-provoking and startlingly unconventional movie, quite unlike anything else on the big screen. It’s not one you’ll find at a multiplex, but it’s definitely worth the price of a ticket at your local indie (or Picturehouse) cinema.

4.3 stars

Susan Singfield