16/03/24

Cineworld, Edinburgh

Since their auspicious debut with Blood Simple way back in 1984 (when I had the honour of interviewing them for Manchester’s City Life magazine), Joel and Ethan Coen have unleashed a whole barrage of brilliant films. OK, so there have been one or two misfires in there, but few filmmakers have been so consistently prolific and on the button.

A few years ago they decided to take a sabbatical and work on their own individual projects. Older brother Joel landed first with The Tragedy of Macbeth, which – despite having possibly the most self-aggrandising screen credit in history – turned out to be one of the finest Shakespeare movie adaptations ever. Now it’s Ethan’s turn and Drive-Away Dolls, co-written with his wife, Tricia Cooke, is the result. The central story is so sniggeringly phallus-obsessed it might just as easily have been written by Beavis and Butthead.

The ‘dolls’ in question are Marian (Geraldine Viswanathan) and Jamie (Margaret Qualley), two lesbian besties. Marian is reserved and socially awkward. She spends most of her spare time reading highbrow literature. Jamie is her polar opposite, with a propensity for raucous and ill-fated relationships. She’s in the process of messily breaking up with policewoman, Sukie (Beanie Feldstein), and urgently needs a change of scenery, so she talks Marian into taking her on a road trip to Tallahassee.

The women hire a drive-away vehicle from Curlie (Bill Camp) and set off on the long drive, blissfully unaware that they have got their wires badly crossed and that the boot of their car contains a metal attaché case containing something of great value. (This device feels so like the MacGuffin in Pulp Fiction, it surely has to be intentional.)

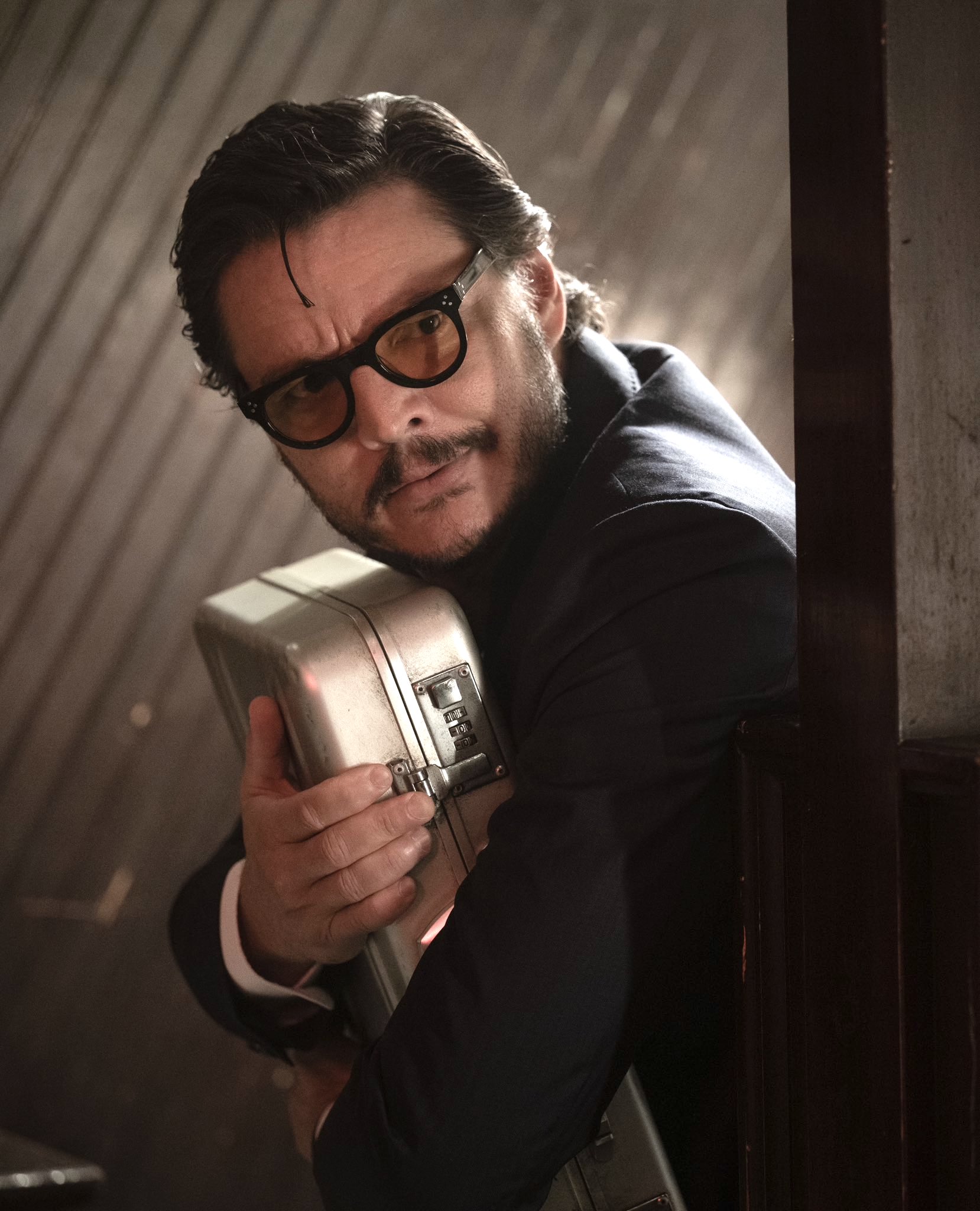

At any rate, Marion and Jamie are being pursued by a trio of bad guys, led by ‘The Chief’ (a criminally underused Colman Domingo), who want what’s in that briefcase. Rough stuff inevitably ensues…

While Drive-Away Dolls feels closer to familiar Coen territory than Shakespeare ever could, it’s exasperating to witness how consistently this fails to hit any of its chosen targets. Viswanathan and Qually are both engaging performers, but Qually in particular is stuck with the unenviable task of delivering slabs of frankly unbelievable dialogue, the kind of lines that no human character would ever utter. Furthermore, the women’s lesbianism is viewed purely through the male gaze: they are incongruously penis-fixated and the camera lingers on their bodies in a salacious fashion, which makes the whole thing feel dated as well as puerile. The villains are so inept that they fail to generate any sense of menace and, meanwhile, a string of A listers, including Matt Damon and Pedro Pascal (who presumably signed up for this on the understanding that it had the name ‘Coen’ attached), are reduced to cameo roles that give them little to do except die.

There are a few funny lines. A couple of weird psychedelic sequences, which seem to have drifted in from an entirely different movie, occasionally attempt to shift this ailing vehicle into a higher gear, but Drive-Away Dolls is a resounding failure that feels hopelessly stuck in first.

The news that the Coens are back together and already working on their next project can only come as a welcome relief.

2.5 stars

Philip Caveney