05/06/25

Traverse Theatre, Edinburgh

It seems at first an act of incredible hubris: to take one of Shakespeare’s most accomplished works, chuck out all those pesky words and attempt to tell the story entirely through movement. But only a few minutes into Raw Material’s adaptation and I am beginning to appreciate what a clever idea this actually is – one that opens out the play’s central story to encompass a whole range of different interpretations. Anybody who has watched helplessly as an aging relative slips inexorably into the fog of dementia, for instance, will find plenty to identify with here.

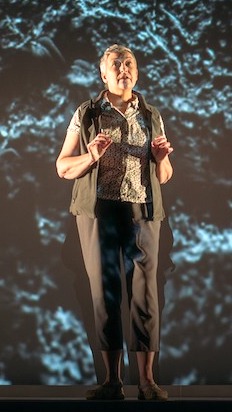

Anna Orton’s simple set comprises mostly heaps of sandbags, which we will soon discover are stuffed with what look like ashes and which, when scattered around the stage, seem to accentuate the central character’s failing grasp on reality. When Lear (Ramesh Meyyappan) first strides confidently into view, he is fearless, energetic, reenacting his past conflicts for the entertainment of his three daughters.

But we cannot fail to notice that he is already jumping at shadows, reacting to every bump and thud of David Paul Jones’s vibrant score, every flash and flicker of Derek Anderson’s vivid lighting design. Director Orla O’Loughlin keeps him centre stage while his daughters move around its periphery, cooly observing as he begins a slow but steady decline. As his grasp on the war-torn kingdom grows ever more precarious, so he goes to his daughters seeking refuge. Regan (Amy Kennedy) and Goneril (Nicole Cooper) are not the grasping, cruel sisters of the source play, but rather two concerned siblings that strive their hardest to accommodate their Father’s eccentricities. Cordelia (Draya Maria) keeps to the sidelines, always giving way to her more manipulative sisters – but her affection for her father is evident, making it clear that she will love him unconditionally.

And then the fog really begins to take hold as Lear don’s his Fool’s old hat and adopts the gurning, slapstick attitude of his former jester, Meyyappan pantomiming exquisitely as he slips effortlessly between the two characters, bicker and competing with each other for the sister’s affections. His bewildered daughters try their best to cope with their father’s mounting instability but once taken hold, these changes cannot be denied. In Lear’s latter stages, stripped to his underwear and no longer able even to wash himself, the character’s ultimate tragedy really begins to hit home.

Lear’s story is also true of so many people as they begin to slip helplessly into their twilight years – as they succumb to drug addiction – as they are weighed down by advancing depression – the transformation witnessed by their partners and their children. This daring adaptation nails such experiences with considerable skill.

Despite my initial reservations, I have to raise my hat to a fearless and thought-provoking piece of theatre.

4.2 stars

Philip Caveney